Huawei: What is 5G's core and why protect it?

PA Media

PA MediaAfter years of deliberation, the UK has finally confirmed Huawei will be allowed to be part of its 5G networks - but with restrictions.

One of those is that the Chinese firm's equipment must be limited to "non-core" parts of the system.

What is the core and why is Huawei being kept out of it?

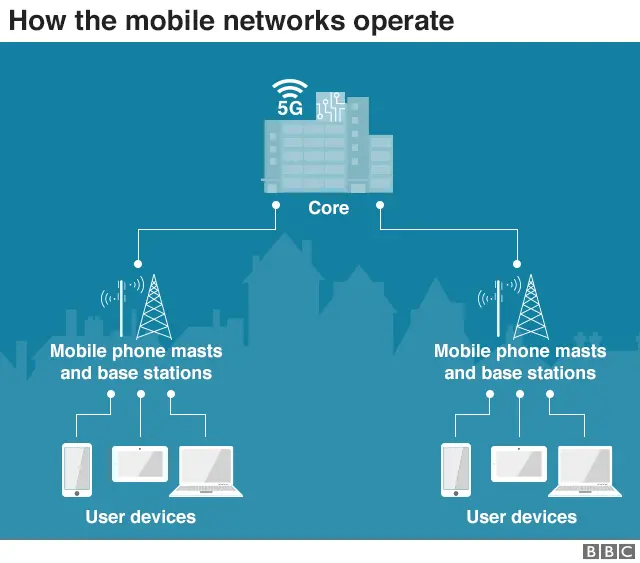

A mobile phone network's core is sometimes likened to its heart or brain.

It is where voice and other data is routed across various sub-networks and computer servers to ensure it gets to its desired destination.

This involves:

- authenticating subscribers so that specific users only get access to the services they have paid for and opted into

- sending a call to the right radio tower to connect to another person's mobile phone

- managing facilities such as call-forwarding and voicemail

- delivering SMS messages and multimedia from one handset to another

- routing data back and forth to third-party services such as apps and websites

- keeping track of usage to calculate an individual's bill

While once, a lot of this involved physical equipment known as routers and switches, in the 5G world much of this kit has been "virtualised". That means software rather than specialised hardware now takes care of much of the job.

This opens the door to new capabilities such as "network slicing", in which operators can offer the emergency services and other priority clients dedicated bandwidth, for example, letting them avoid sluggish speeds during periods of peak demand.

It also lets some network activity be physically carried out closer to users' devices, helping reduce latency. That should help cloud gaming services run with less lag time between a user pressing a gamepad button and the on-screen character responding. Self-drive cars should also benefit, in theory, from being able to co-ordinate their movements more fluidly.

But a perceived risk is that this shift to virtualisation could open the system up to new kinds of attack. And even if encryption means the information being handled cannot be spied upon, the fear is that a rogue participant could still crash the network - or at least disrupt the data flow.

How does this differ from the rest of the network?

The core is distinct from the Radio Access Network (RAN), which is sometimes referred to as the "periphery".

It includes the base stations and antennas used to provide a link between individual mobile devices and the core.

Insiders sometimes describe this as the "innovative but dumb" part of the network. That is because new traffic management software and other advances mean more traffic can be handled than before, but the equipment does not actually affect what happens to the data itself beyond transmitting it back and forth.

Although it has commonly been reported that Huawei's advantage here is cost, industry insiders say a bigger advantage is that it can currently do the same job as its rivals using fewer antennas. That means fewer planning permission requests need to be approved, and 5G can be rolled out more quickly as a result.

The theory is that by limiting Huawei to the RAN but banning it from the core, the authorities make the risk of its involvement more "manageable".

So why are the Americans still worried?

The Trump administration's cyber-security chiefs, along with their Australian counterparts, contend that over time the "edge" - the name given to the boundary between the core and periphery - will disappear, as more and more sensitive operations are carried out closer to users.

As a result, it will no longer be possible to keep Huawei, and by extension the Chinese state, out of the network's most sensitive areas, they claim.

UK network operators acknowledge that over time more functions will indeed move from centralised sites to individual exchanges and even base stations themselves. But they are adamant that they can still design the architecture of their networks to keep the core distinct and protect it with firewalls, probes and other measures.

As such, 5G should never evolve into a system where data is simply bounced from device to antenna to device, without having to go through a secured core where each user must still be authenticated, helping safeguard the system.

However, some security experts warn that this kind of segmentation might still not prevent the RAN being used to mount an attack.

"This is not a foolproof plan, as networks are dynamic and managed by people - who make mistakes," commented Elad Ben-Meir of Scadafence - an industrial security specialist.

"So, over time this ring-fencing may be broken or even worse, may have a vulnerability or weakness which could be utilised by threat actors."