Scientists probe the secrets of mega icebergs

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUK scientists are seeking to understand the triggers that result in the production of giant Antarctic icebergs.

Nearly half the ice lost from the white continent comes from the shedding of these often city-sized frozen blocks.

This makes them a major consideration in forecasts of future sea level rise.

British researchers hope to glean new insights into the physics of ice fracturing by studying a sector of the Antarctic that recently saw the breakaway of two mega-bergs.

The expectation is that the work will lead to models that better predict where and when events known as calvings might occur. Scientists use the term "calving" to describe an iceberg breakaway - like a cow giving birth to her young.

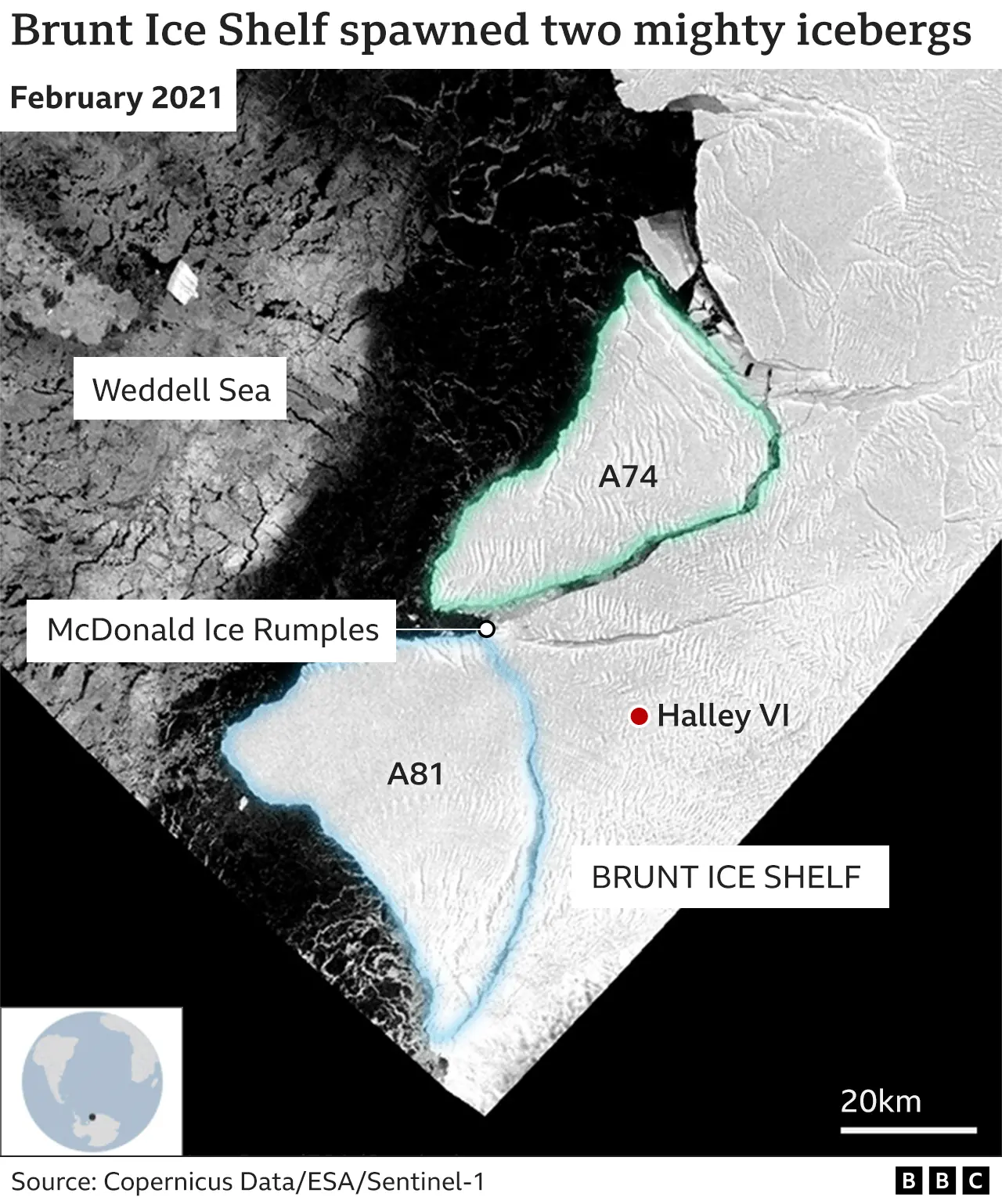

The region under study is the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is the floating protrusion of glaciers that have flowed off the continent into the Weddell Sea.

In 2021, the shelf produced a berg the size of Greater Paris - 1,300 sq km/810 sq miles - called A74, followed in 2023 by an even bigger block called A81 that was, at 1,500 sq km (930 sq miles), the size of Greater London.

Researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have just returned from the Brunt Ice Shelf, where they deployed an array of instrumentation - including seismometers, radar and GPS receivers - on the remaining shelf structure.

Their goal was to gather information on the propagation of cracks in the ice.

The team also drilled into the shelf. The aim here was to learn about the physical properties of the ice.

Shelves like the Brunt are not uniform bodies but rather an amalgam of different ice types.

Some areas will be made from rock-hard glacier ice that flowed off the continent, while other areas will be sea-ice and snow that has filled gaps to act almost like a glue to hold various segments of the shelf together.

The drilling sought to retrieve examples of the different ice types.

"When we get these cores back to the lab, we're going to crush them," said Dr Liz Thomas.

"It's all about understanding physical strength. We're going to put a lot of pressure on the ice to see where it breaks. Is it on a slant? Is it going to just crush and crumble? This will help explain why these big bergs are able to break away," she told BBC News.

BAS/Emma Pearce

BAS/Emma PearceThe expectation is that the lessons learned will apply not just to the Brunt but to other sectors of the Antarctic as well. About 75% of the continent's margin has floating platforms of ice that can eject bergs.

The shedding of large segments of ice at the forward edge of a shelf is a natural behaviour.

A shelf will be in equilibrium if the ejection of bergs balances the snowfall and ice that builds the glacier from behind.

An assault by warm water at the front of the shelf could knock it out of balance but there is no evidence this is happening at the Brunt, currently.

It is certainly true, however, that in other parts of the continent we have seen warmer conditions trigger whole-shelf collapse, producing a splurge of bergs. Spectacularly so.

BAS

BAS"In some areas of Antarctica, we've seen that with our changing climate an instability has been induced that has led to the shelves flowing and calving at an accelerated rate," explained Dr Emma Pearce.

"This acts like removing the cork in a champagne bottle, allowing the ice behind to then flow into the sea at an accelerated rate, leading to an increase in sea level.

"The processes associated with this are not particularly well understood and for us to be able to reduce our uncertainty on sea level predictions, we really need to get a better control on that."

BAS/Emma Pearce

BAS/Emma PearceThe Brunt experienced a rapid acceleration in its seaward movement after the loss of A74 and A81.

Historically, it has flowed forward at a rate of 400-800m (1,300-2,600ft) per year. With the bergs' departure, this rate jumped as high as 1,500m (4,900ft) a year.

It's now fallen back slightly to 1,300m (4,300ft) a year.

BAS/Emma Pearce

BAS/Emma PearceThe study's outcome is certain to be reviewed in the UK's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

The Brunt is the site of Halley VI, one of Britain's two big Antarctic research stations.

A base has flown the union flag on the shelf since 1956. The FCDO has a clear interest, therefore, in knowing UK infrastructure is secure and not about to drift off into the ocean atop another iceberg.

The base was moved 23km (14 miles) upstream of the ice flow in 2017 to take it away from the chasm that was about to spawn A81.

It might sound foolhardy to position a station on an active ice shelf but Dr Oliver Marsh said it had its advantages.

"Having a station on an ice shelf with cracks is actually helping us to do detailed studies that wouldn't otherwise be possible," he told BBC News.

The BAS scientists are describing their investigations in talks at this week's European Geosciences Union General Assembly meeting in Vienna.