Fingerprints of city-sized icebergs found off UK coast

James Kirkham

James KirkhamIcebergs as large as cities, potentially tens of kilometres wide, once roved the coasts of the UK, according to scientists.

Researchers found distinctive scratch marks left by the drifting icebergs as they gouged deep tracks into the North Sea floor more than 18,000 years ago.

It's the first hard evidence that the ice sheet formerly covering Britain and Ireland produced such large bergs.

The findings could provide vital clues in understanding how climate change is affecting Antarctica today.

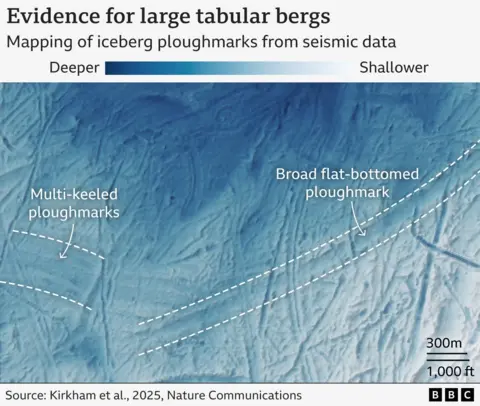

The scientists searched for fingerprints of giant icebergs using very detailed 3D seismic data, collected by oil and gas companies or wind turbine projects doing ocean surveys.

This is a bit like doing an MRI scan of the sediment layers beneath the present-day seafloor, going back millions of years.

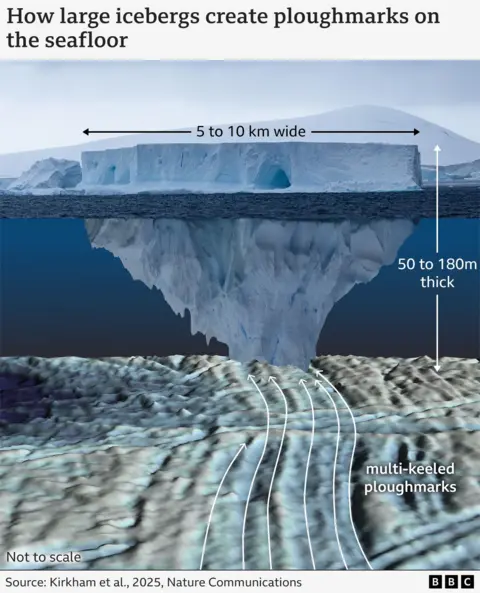

The researchers found deep, comb-like grooves, interpreted to have been created by the keels of large icebergs that broke off the British-Irish ice sheet more than 18,000 years ago.

Some of these scratch marks are as close as 90 miles (145km) to Scotland's present-day east coast.

"We found [evidence of] these gigantic tabular icebergs, which basically means the shape of a table, with incredibly wide and flat tops," said James Kirkham, marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and lead author of the new study, published in the journal Nature Communications.

"These have not been seen before and it shows definitively that the UK had ice shelves, because that's the only way to produce these gigantic tabular icebergs."

Ice shelves are floating platforms of ice where glaciers extend out into the ocean.

By analysing the size of the grooves, the scientists estimate that these icebergs could be five to tens of kilometres wide and 50-180m thick, although it's difficult to be exact.

That means they would have covered an area roughly as big as medium-sized UK cities like Norwich or Cambridge.

The icebergs are comparable in size to some of the smaller icebergs found off present-day Antarctica, such as blocks that calved from the Larsen B ice shelf in 2002.

Dr Kirkham described seeing such an iceberg when working in Antarctica two years ago.

"Those of us working on this paper were standing together, gazing out onto this iceberg and thinking, 'Wow, that's probably a similar size iceberg to what was found off the shore of Scotland 18,000 years ago, right in front of us in Antarctica today.'"

Clues for Antarctica?

Hundreds of ice shelves surround about three-quarters of today's Antarctic ice sheet, helping to hold back its vast glaciers.

But if ice shelves are lost, the glaciers behind can speed up, depositing more and more ice into the ocean and raising sea levels worldwide.

Exactly how this plays out, though, is "one of the largest sources of uncertainty in our models of sea level rise", Dr Kirkham told BBC News.

That's partly because scientists have only been able to use satellites for a few decades to observe about 10 cases of ice shelves collapsing - hence the desire to look for examples further back in time.

No ice shelf setting is the same, but the researchers say their findings from the former British-Irish ice sheet could help understand how Antarctica might respond to today's rapidly warming climate.

By looking at the changing scratch marks on the seafloor, the researchers discovered an abrupt shift in Britain's icebergs about 18,000 years ago, a time when the planet was gradually warming from a very cold period.

The occasional production of giant bergs ceased. Instead, smaller ones were produced much more frequently.

That indicates that the ice shelves suddenly disintegrated; without these massive floating platforms, such large icebergs could no longer be produced.

And it's potentially important because this coincides with the time when the glaciers behind began to retreat faster and faster.

The crucial, but unresolved, question is whether the disintegration of Britain's former ice shelves was merely a symptom of a quickly melting ice sheet - or whether the loss of these shelves directly triggered the runaway retreat of ice.

Resolving this chicken-and-egg dilemma, as Dr Kirkham put it, would shed light on how serious the impacts of losing today's Antarctic ice shelves might be.

"These ocean records are fascinating and have implications for Antarctica, as they illustrate the fundamental role of ice shelves in buttressing [holding back] the flow of continental ice into the ocean," said Prof Eric Rignot, glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study.

"But the argument that the collapse of ice shelves triggered ice sheet collapse is only part of the story; the main forcing is warmer air temperature and warmer ocean temperature," he argued.

Graphics by Erwan Rivault