Nasa spacecraft lining up to smash into an asteroid

NASA/JHU-APL

NASA/JHU-APLIn the coming hours, the American space agency will crash a probe into an asteroid.

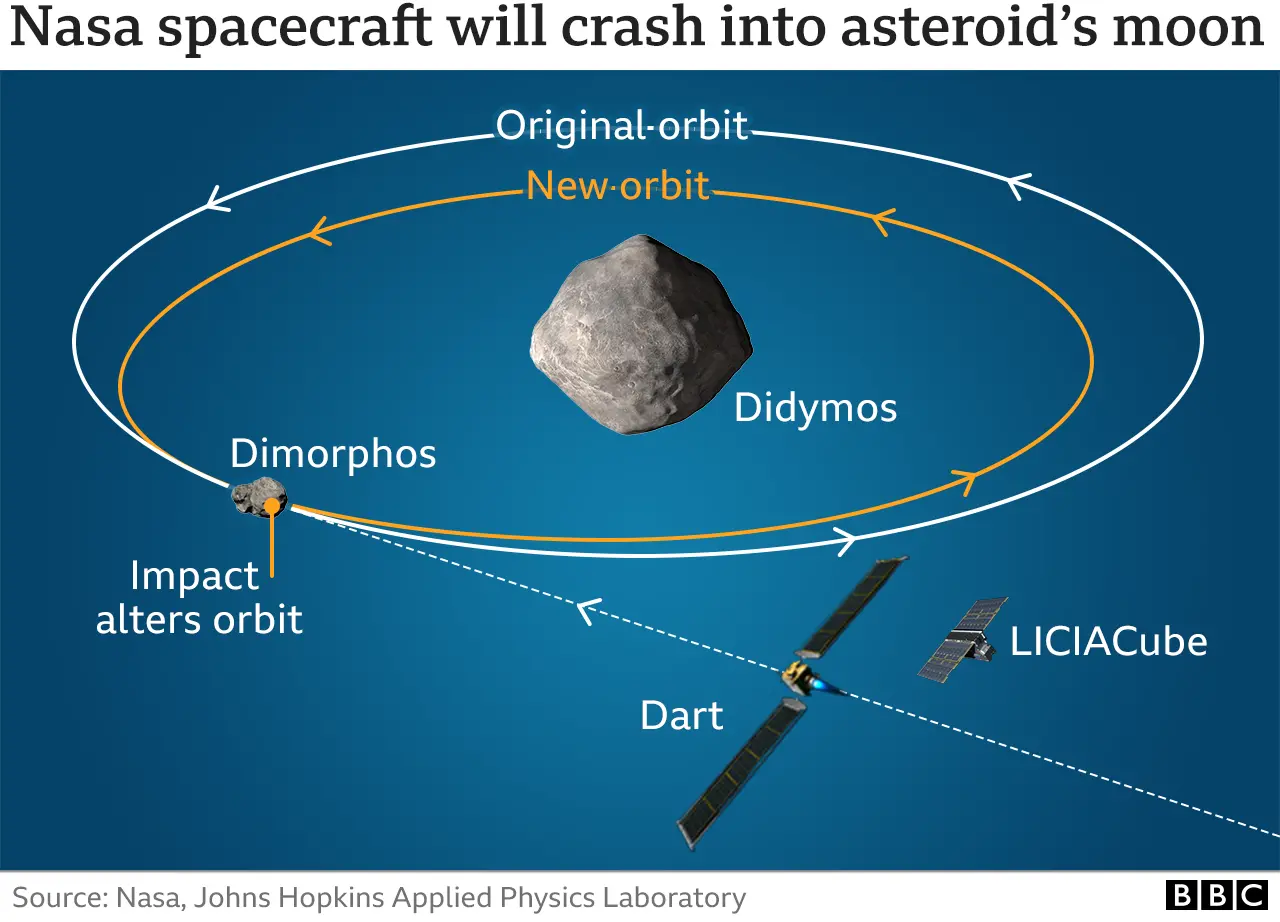

Nasa's Dart mission wants to see how difficult it would be to stop a sizeable space rock from hitting Earth.

The demonstration is taking place some 11 million km away (7 million miles) on a target called Dimorphos.

The agency says the rock is not currently on a path to hit the Earth, nor will the test accidentally send it in our direction.

The impact is timed for 23:14 GMT, Monday (00:14 BST, Tuesday). Telescopes will be watching from afar, including the new super space observatory James Webb.

We've all seen how Hollywood would do it, with brave astronauts and nuclear weapons. But how do you protect Earth from a killer asteroid for real?

Nasa is about to find out. Its idea is simply to smash a spacecraft into one.

The thinking is you would only need to change the rock's velocity by a small amount to alter its path so that it misses Earth - provided you do it far enough in advance.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (Dart) mission will check out this theory with a near-head-on crash into 160m-wide Dimorphos at over 20,000km/h.

This should change its orbit around a much larger asteroid, called Didymos, by just a few minutes every day.

Nasa is promising some spectacular images from the 570kg-Dart probe as it goes in for the hit.

"Dart is the first planetary defence test mission to demonstrate running a spacecraft into an asteroid to move the position of that asteroid ever so slightly in space," explained Dr Nancy Chabot from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, which leads the mission for Nasa.

"This is the sort of thing, if you needed to, that you would do years in advance to just give the asteroid a small nudge to change its future position so that the Earth and the asteroid wouldn't be on a collision course," she told BBC News.

Hitting Dimorphos will be quite the challenge. It's only in the last 50 minutes or so that Dart will be able to distinguish its target from 780m-wide Didymos.

Navigation software must then adjust the spacecraft's trajectory to make a direct hit.

"Because of the speed of light and the distances involved, it's really not feasible for there to be a pilot sitting on the ground with a stick controlling the spacecraft. There just isn't enough time to respond," said Dr Tom Statler, the Dart programme scientist at Nasa.

"We've had to develop software that can interpret images taken by the spacecraft, figure out what is the right target and make the course correction manoeuvres by firing thrusters."

Dart will be returning images to Earth at the rate of one per second as it heads towards its "deep impact". What at first will appear as a dot of light in the pictures will quickly grow to fill the entire field of view, before the feed then suddenly cuts out as the spacecraft is destroyed.

Fortunately, that's not the end of the story. Dart has carried with it a 14kg Italian cubesat that was released some days ago. Its job is to record what happens when Dart digs out a crater.

Its pictures, snapped from the safe distance of 50km, will be beamed back to Earth over the coming days.

"LiciaCube will pass about three minutes after Dart's impact," said Simone Pirrotta from the Italian space agency (ASI).

"This timing has been selected in order to allow the plume of ejecta to be completely developed, because one of the major contributions of LiciaCube is to document the plume to support the measurement of the parameters that confirm the deflection of the orbit."

Currently, Dimorphos takes roughly 11 hours and 55 minutes to circle Didymos. The impact is expected to change the smaller object's momentum such that the orbital period is reduced to something in the order of 11 hours and 45 minutes. Telescope measurements will confirm this in the weeks and months ahead.

HERA/ESA

HERA/ESASurveys of the sky combined with statistical analyses suggest we have identified more than 95% of the monster asteroids that could initiate a global extinction were they to collide with Earth (they won't; their paths have been computed and they won't come near our planet). But this still leaves many so-far undetected smaller objects that could create havoc, if only on the regional or city scale.

An object like Dimorphos, were it to hit Earth (it won't), might dig out a crater perhaps 1km across and a couple of hundred meters deep. The damage in the vicinity of the impact would be intense.

Four years from now, the European Space Agency (Esa) will have three spacecraft - collectively known as the Hera mission - at Didymos and Dimorphos to make follow-up studies.