Nasa's Lucy mission will seek out Solar System 'fossils'

Reuters

ReutersA spacecraft has launched from Cape Canaveral on a mission to uncover "the fossils" of the Solar System.

The Lucy probe will head out to the orbit of Jupiter to study two groups of asteroids that run in swarms ahead of, and behind, the gas giant.

US space agency (Nasa) scientists say the objects are leftovers from the formation of the planets.

As such, these trojans, as they're known, hold important clues about the early evolution of the Solar System.

Lift-off, aboard an Atlas-V rocket from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, went ahead on schedule at 05:34 EDT (09:34 GMT; 10:34 BST).

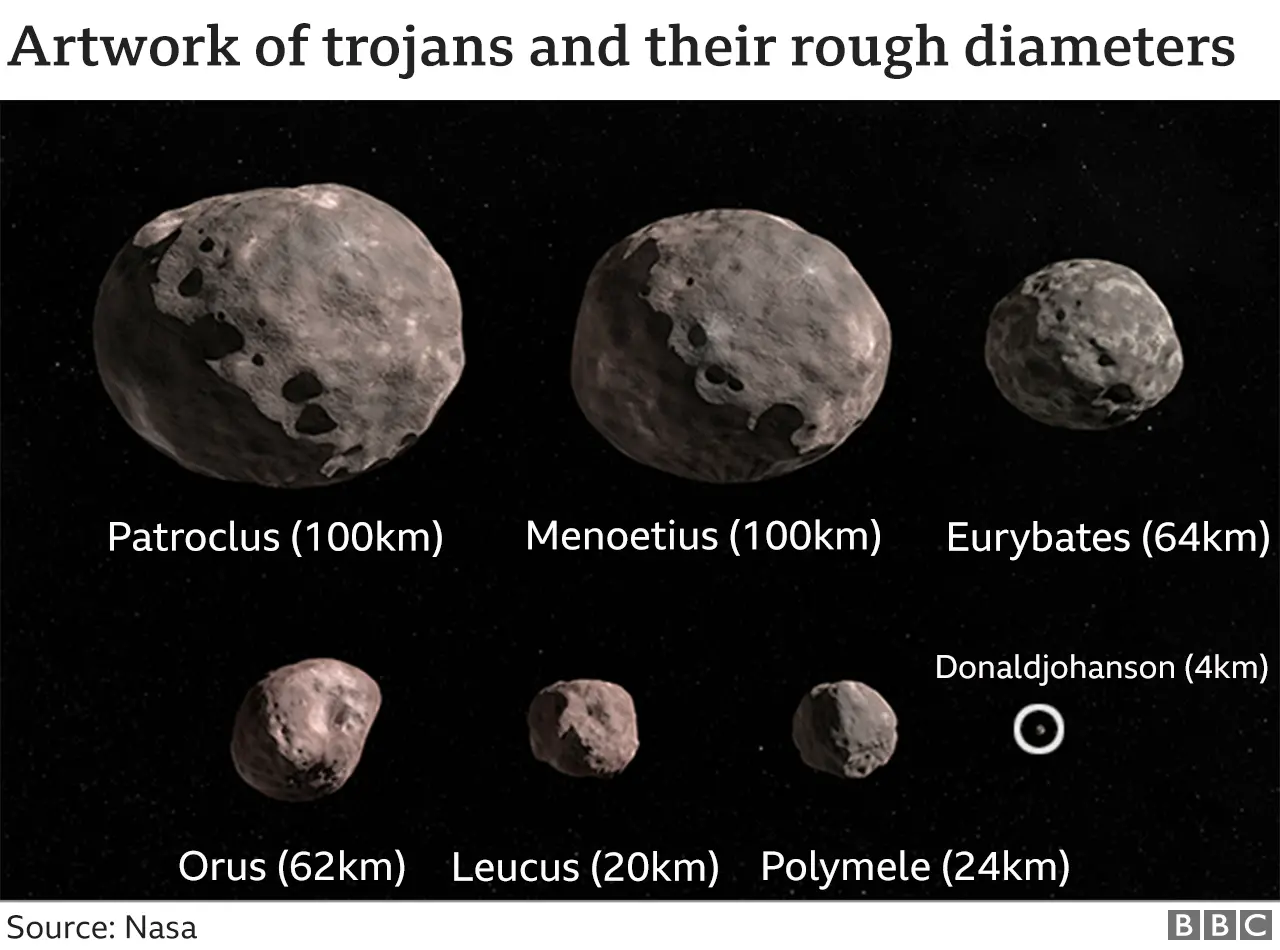

Nasa has initially committed $981m (£720m), over 12 years, for the mission. In this time, the Lucy probe will visit seven trojans.

Jason Kuffer CC

Jason Kuffer CCThere is a famous human fossil from Africa that was nicknamed Lucy, which taught us much about where our species came from. And this new Nasa mission takes direct inspiration - and the name - from that origins story, except the fossils this spacecraft seeks are hundreds of millions of km from Earth, circling the Sun in formation with Jupiter.

"The trojan asteroids lead or follow Jupiter in its orbit by about 60 degrees," explained Hal Levison, Lucy's principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado.

"They're held there by the gravitational effect of Jupiter and the Sun. And if you put an object there early in the Solar System's history, it's been stable forever. So, these things really are the fossils of what planets formed from," he told reporters.

NASA/SwRI

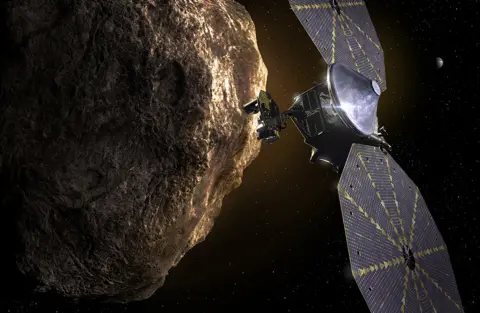

NASA/SwRILucy will use its instrumentation to study the city-sized (and bigger) objects, detailing their shape, structure, surface features, composition and temperature.

If the trojans are made from the same sorts of materials as Jupiter's moons, it would suggest they formed at the same distance from the Sun as the gas giant. But this isn't the expectation.

"If, for example, they're made of the sorts of things we see much further out in what we call the the Kuiper Belt, then that tells us they might have formed out there and then at some point got pulled inward," said SwRI mission scientist Dr Carly Howett.

"This mission is a test of our models. We have this theory that there was a big re-juggle of objects early in Solar System history, when some things gravitationally got thrown out and some got thrown in. The evidence points to this billiard ball theory, but we'll be able a check on that," she told BBC News.

The mission plan is the result of some extraordinary navigational calculations.

Solar System dynamicists worked out that if the probe periodically returns to make a flyby of Earth, it can use a sling-shot effect to visit both trojan swarms.

Saturday's launch would see Lucy make its encounter with the leading group of trojans in 2027/28, followed by a tour of the trailing cluster in 2033. The total travel distance is over 6 billion km (4 billion miles).

Leading swarm:

- Eurybates and Queta (moon) - August 2027

- Polymele - September 2027

- Leucus - April 2028

- Orus - November 2028

Trailing swarm:

- Patroclus and Menoetius - March 2033

Main-belt asteroid:

- Donaldjohanson - April 2025

"What's amazing about this trajectory is that we can continue to do loops through the swarms, as long as the spacecraft is healthy. And so after the final encounter with Patroclus and Menoetius, we plan to propose to Nasa to do an extended mission to explore more trojans," said Coralie Adam from KinetX Aerospace, which is providing navigation support to the project.

Although focused on the trojans, Lucy will also visit a different type of asteroid on the way out to Jupiter's orbit - an object called Donaldjohanson (sic), named after the palaeoanthropologist who discovered the Ethiopian human fossil skeleton in 1974.

Nasa/Glenn Benson

Nasa/Glenn BensonThe spacecraft shares a lot of engineering heritage with Nasa's New Horizon's mission, which made the first - and to date only - flyby of Pluto in 2015.

Lucy carries updated versions of some of New Horizons' main instruments.

A big difference is the power source. Whereas the Pluto probe drew its energy from a nuclear battery, Lucy is flying with two, fan-like solar panels.

These "wings" are huge, over 7m in diameter. They have to be that big to generate sufficient electricity to drive the spacecraft's systems at the more dimly lit distance of Jupiter's orbit.

"When we're near Earth, those wings have about 18,000 watts of power. That would be equivalent to powering up my house and a couple of my neighbours'," explained Katie Oakman, from spacecraft manufacturer Lockheed Martin.

"However, when we fly Lucy out to the trojan asteroids, we only have about 500 watts of power. That would only light a few light bulbs, and it wouldn't be enough to power up my microwave in the morning to warm my coffee."

Fortunately, Lucy's instruments only need 82 watts to do their job.

Lucy represents another stage in what is turning out to be a golden age for asteroid study by Nasa.

The agency's Osiris-Rex mission is just now heading home after picking up samples from the surface of an object known as Bennu.

Next year, Nasa will launch the Psyche spacecraft to a metal asteroid, also called Psyche.

"It's really the time for asteroids, and I'm expecting a leap in understanding," said Dr Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for science.

"To understand any population, we need multiple measurements of different types of asteroids. That's exactly what we're doing.

"You didn't mention it but I will. Asteroids can threaten the Earth and in November we will launch a collision experiment called Dart. It will be followed up by Europe's Hera mission and will help find out if you can impart momentum to a threatening object," he told BBC News.