Immense crater hole created in Tonga volcano

BBC

BBCResearchers have just finished mapping the mouth of the underwater Tongan volcano that, on 15 January, produced Earth's biggest atmospheric explosion in over a century.

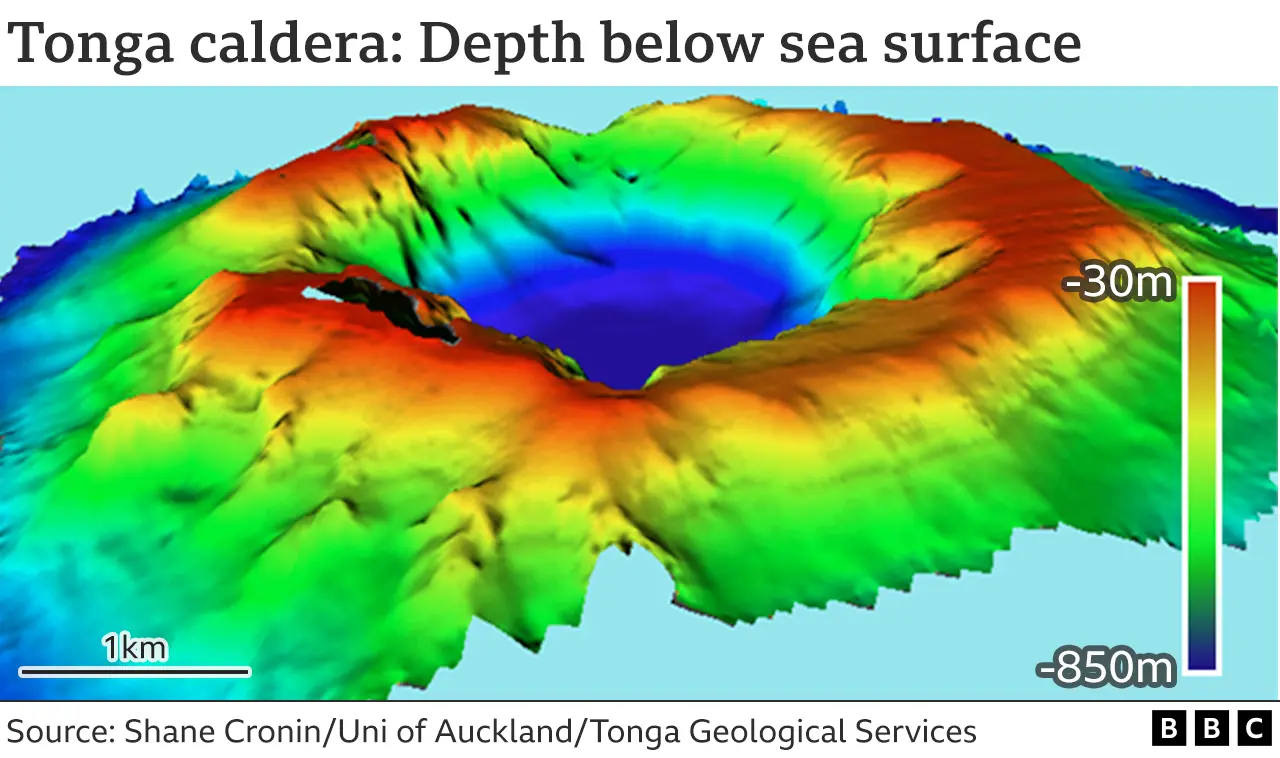

The caldera of Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha'apai is now 4km (2.5 miles) wide and drops to a base 850m below sea level.

Before the catastrophic eruption, the base was at a depth of about 150m.

It drives home the scale of the volume of material ejected by the volcano - at least 6.5 cubic km of ash and rock.

"If all of Tongatapu, the main island of Tonga, was scraped to sea level, it would fill only two-thirds of the caldera," Prof Shane Cronin from the University of Auckland, New Zealand, said.

Prof Cronin has spent the past two and a half months in the Pacific kingdom, seconded to its geological services department.

Their report, issued on Tuesday, assesses the eruption and makes recommendations for future resilience.

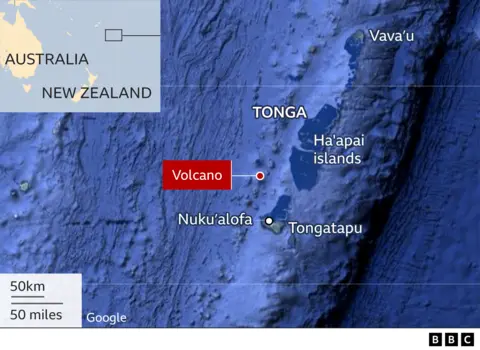

Although Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha'apai (HTHH) is unlikely to give a repeat performance for many hundreds of years, there are at least 10 volcanic seamounts in the wider region of the south-west Pacific that could produce something similar on a shorter timescale.

New Zealand's National Institute for Water and Atmospheric (NIWA) Research released its bathymetry (depth) map for the area immediately around the volcano, on Monday.

But the agency has yet to take soundings directly over the top of HTHH.

So Prof Cronin and colleagues' data literally fills a hole in the NIWA survey.

A comparison with pre-eruption maps of the caldera, made in 2016 and 2015, shows the major changes.

In addition to a general deepening, big chunks have been lost from the interior cliff walls, particularly at the southern end of the crater.

There is evidence of continued infall of loose material - but on the whole, the volcano cone as it stands today looks structurally sound.

"Eventually, the caldera will be a little bit bigger in diameter and a little bit shallower as the sides collapse inwards," Prof Cronin told BBC News. "So we'll have ongoing interest.

"The north-eastern side looks a bit thin and if that failed, a tsunami would endanger the Ha'apai islands. But the volcano's structure does look pretty robust."

Scientists are beginning to get a good handle on how the eruption progressed - and was powered.

The wealth of observational data from 15 January suggests the event became supercharged in the half-hour after 17:00 local time.

As the caldera cracked, seawater was able to interact with decompressing hot magma being drawn up rapidly from depth.

"There were sonic booms as you got large-scale magma-water interactions," Prof Cronin said. "So an explosion followed by water flushing back in again and then another explosion followed by water flushing back in again, explosion - and away we go... like an engine."

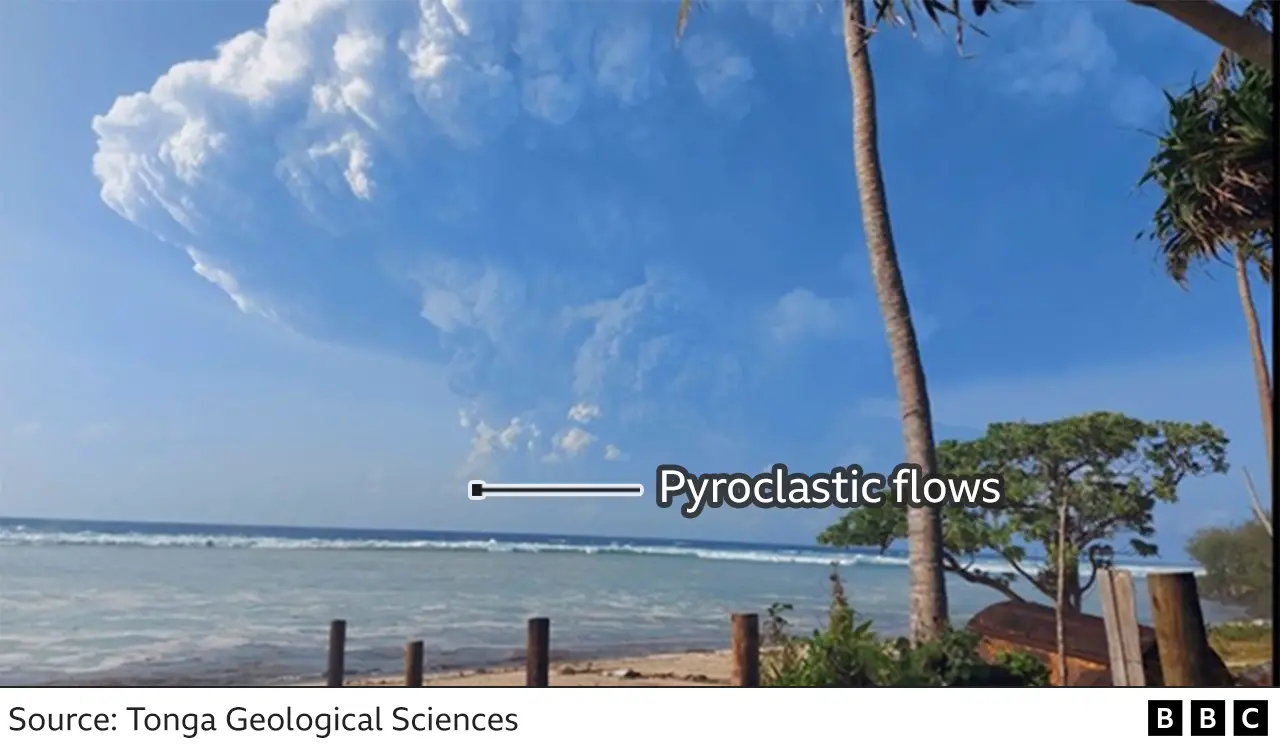

Prof Cronin highlighted the significance of pyroclastic flows in the eruption.

These thick dense clouds of ash and rock thrown into the sky fall back to roll down the sides of the volcano and along the ocean floor.

They will have caused much of the tsunami wave activity that inundated coastlines across the Tongan archipelago.

Prof Cronin accompanied staff from the Tonga Geological Services department to more than 80 locations on various islands, to document one of the most widespread and destructive tsunami events known from a volcano, with waves running up above:

- 18m at Kanokupolu, on western Tongatapu (65km south of HTHH)

- 20m on Nomukeiki Island (a similar distance but to the north-east)

- 10m on islands at distances greater than 85km from the volcano

Consulate of the Kingdom of Tonga

Consulate of the Kingdom of TongaThe investigations have informed a report for Tonga's Ministry for Lands and Natural Resources.

Rather than rebuilding like-for-like tourism resorts in low-lying areas, it suggests developing "Mediterranean-style", or "pop-up", day-use beach reserves and parks, with the resort accommodation on higher, more landward sites.

"They should also plant a whole lot more trees, like mango," Prof Cronin said.

"They fall over when the tsunami moves through - but they create these log dams and these really reduce the flow energy of the waves."

NIWA, with a UK partner, Sea-Kit International, will shortly make another caldera map. This will be useful to gauge ongoing sediment movement at the crater edges, and continued low-level venting from inside the volcano.

Hear more from Prof Cronin in Thursday's Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service with Roland Pease.