Tonga volcano: Plume reached half-way to space

BBC

BBCAn indicator of the great power of last Saturday's volcanic eruption in Tonga is the height reached by its plume.

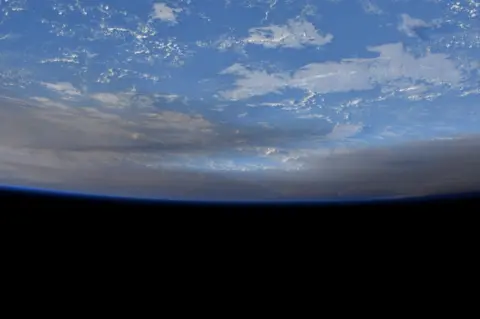

UK scientists examining weather satellite data calculate it to be around 55km (35 miles) above the Earth's surface.

This is at the boundary of the stratosphere and mesosphere layers in the atmosphere.

Dr Simon Proud, from RAL Space, said these were "unheard-of altitudes" for a volcanic plume.

The most powerful eruption in the second half of the 20th Century came from Mount Pinatubo in 1991. Its plume is thought to have climbed to roughly 40km.

However, it's possible today's more accurate satellites would have given a higher altitude for the Philippines event, cautioned Dr Proud, who is affiliated to the UK National Centre for Earth Observation.

NASA

NASATo work out the position in the sky of the plume from Tonga's Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha'apai volcano, data from three weather satellites - Himawari-8 (Japan) GOES-17 (USA) and GK2A (Korean) - was used.

"Because they're all at different longitudes, we can use the parallax between their views of the eruption to determine altitude. This is a pretty well established technique for storm cloud heights, and should actually work better here as the altitude [and hence parallax] is greater," Dr Proud told BBC News.

Only a small part of the cloud is seen to get to 55km. This is most likely water vapour, rather than ash, that was pushed upward at the head of the updraft. The main umbrella of the plume is at 35km. A lower plume feature is evident in the lowest layer of the atmosphere - the troposphere.

The so-called Kármán line, which is often quoted as the atmospheric boundary with outer space, is at 100km.

Tonga's deadly tsunami

US space agency scientists calculated the explosive force to be equivalent to 10 megatons of TNT, which would have made the Tonga event 500 times as powerful as the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, at the end of World War Two.

Prof Shane Cronin, from Auckland University, New Zealand, believes a special set of conditions came together at the underwater volcano to drive a big explosion.

A key factor, he said, was the depth below the ocean surface at which gas-rich magma came into contact with seawater - at just 150-250m.

"When the magma came out, there was not much pressure on it [from the water above]," he told the BBC's Science In Action programme on World Service Radio.

"The gases expanded and blasted the magma apart. And then, as those little fragments of hot magma at 1,100 degrees encountered the cold seawater at 20 degrees, it flashed the seawater around those particles into steam. And when you do that, when you flash water into steam, you basically expand the volume by 70 times. So you supercharge your eruption."

TONGA GEOLOGICAL SERVICES

TONGA GEOLOGICAL SERVICES

Early data suggests the Tonga event could have measured as high as five on the volcanic explosivity index (VEI). This would certainly make it the most powerful eruption since Pinatubo, which was classified at six on the eight-point scale.

The Philippines volcano famously dropped Earth's average global temperature by half a degree for a couple of years. It did this by injecting 15 million tonnes of sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere. SO2 combines with water to make a haze of tiny droplets, or aerosols, that reflect incoming solar radiation.

However, Dr Richard Betts, the head of climate impacts at the UK Met Office, said Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha'apai would not have the same effect.

"Pinatubo did have a noticeable effect, but the Hunga-Tonga volcano's emissions were more than 30 times smaller at less than half a million tonnes of sulphur dioxide, so we don't expect that to have a cooling effect, even though it made a huge bang when it went off," he explained.