The 'monster' iceberg: What happened next?

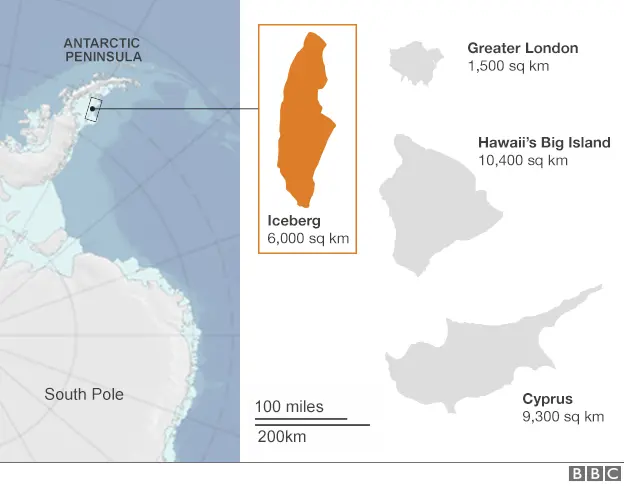

It was a wow! moment. The world's biggest berg, a block of ice a quarter the size of Wales, fell off the Antarctic in July 2017. But what then? We've gone back to find out.

Weighing a trillion tonnes and covering an area of nearly 6,000 sq km, the colossus dubbed A-68 has kind of spent the past 12 months shuffling on the spot - rather like a driver trying to get themselves out of a tight parking spot at the supermarket.

Occasionally, the berg head-butted the floating shelf of ice from which it calved, but made only limited progress in moving north - its expected path out of the Antarctic's Weddell Sea towards the Atlantic Ocean.

"An iceberg as massive as A-68 is sluggish, and thus needs time to accelerate," explains Thomas Rackow from Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute.

"Compared to much smaller icebergs, A-68 is also less sensitive to offshore winds that could potentially drive the iceberg away from the continent. In fact, since the calving event in early July last year, we could see the iceberg going back and forth due to the prevailing winds."

Dr Rackow says the frozen ocean surface probably also played some role in constraining the berg's movement, and wonders if the underside of the berg was catching on the seafloor.

It's a thought shared by Suzanne Bevan at Swansea University, UK. "We know so little about the bathymetry (depth) in that area of the Weddell Sea," she told BBC News. Given time, though, A-68 should pick up the pace as the currents grab hold of it.

And A-68 hasn't melted?

Nope. It's extremely cold in that part of the world. The berg has knocked off some of its sharp edges, but it remains much as it was - 150km long and 55km wide.

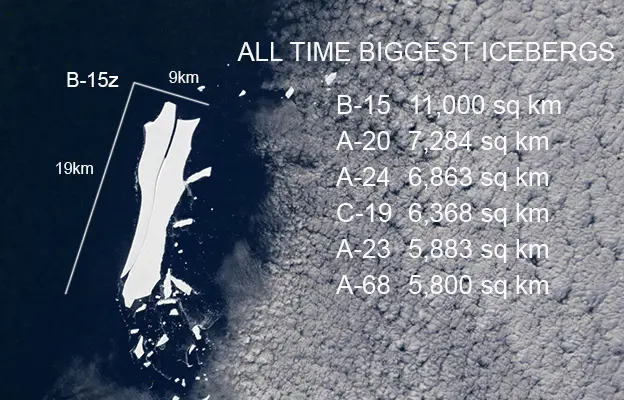

Two largish chunks have detached, one of them sufficiently big to get its own designation (A-68b) in the list of giant bergs kept by the US National Ice Center. The American agency has officially now put A-68 at number six in its all-time ranking.

If you were wondering - a berg called B15 is the historic champ. It was roughly 11,000 sq km in area when it broke away from Antarctica back in 2000. And it's still going, albeit in pieces.

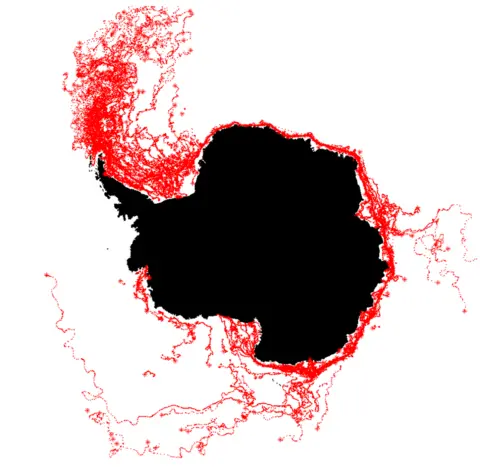

Astronauts on the space station recently photographed the largest remaining fragment of B15 passing the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia on its way to the equator. A-68 will very probably travel this same "iceberg alley".

NASA/ISS

NASA/ISSWhat's A-68 like if you go there?

Ella Gilbert from the British Antarctic Survey was the first to make a movie of the berg from close quarters.

The scientist was in a small plane gathering atmospheric data when she made a low pass along its edge.

"It took us an hour and a half to go from one side to the other," she says. "It's scale is mind-boggling, fascinating - it's like another world. It was possibly the most exciting thing I've ever done."

Ella is often asked why the berg broke away. "It's complicated," she explains. "The region is clearly undergoing a lot of change but you can't just say 'it was the climate'. Iceberg calving is a natural process anyway. If you put more snow in at one end, it has to come out the other end as icebergs."

BAS/A.Rose

BAS/A.RoseSo, why should we be interested?

A-68 broke away from the Larsen C Ice Shelf - the floating extension of glaciers running off the Antarctic Peninsula. The shelf is the subject of intense scrutiny because similar structures to the north have disintegrated.

Climate warming very probably was implicated in some of these losses, and so it is inevitable that people will ask what the future holds for Larsen C.

It is one of the biggest ice shelves in all of Antarctica and its collapse would allow its feeding glaciers to dump more of their ice into the ocean, raising sea-levels.

How likely is that to happen?

The answer to this question will only come with ongoing monitoring. The first thing scientists want to understand is how the shelf will react to calving such a big berg.

The stresses acting on the shelf will almost certainly have changed. "The models tell us we should expect the centre of the Larsen C Ice Shelf to speed up a bit, and the edges, where the berg was attached, to slow down," says Swansea's Adrian Luckman, whose Midas research group was most closely involved in monitoring A-68's break-away.

But this behaviour is very difficult to demonstrate because tidal movements push on the shelf and complicate the satellite measurements.

NASA/John Sonntag

NASA/John SonntagTell me about a surprising discovery

Scientists have established that the surface of the Larsen C Ice Shelf can melt even during the deep freeze of permanent night in the Antarctic winter.

Weather station and satellite observations have established that a particular type of warm westerly wind, or Foehn, will flow down off the peninsula mountains to produce ponds on the surface of the shelf.

"You see this in May, which in the Antarctic is equivalent to late November. Forty percent of the melt in 2016 occurred in this winter period - all because of the Foehn effect," says Adrian Luckman.

This is a process scientists will need to watch closely. Some of those northern shelves that collapsed were destabilised by the presence of large numbers of meltwater lakes on their surface.

Larsen C is far from replicating such conditions but that may change in the coming decades if global warming progresses as expected and its effects impinge deeper into the Antarctic.

NASA/John Sonntag

NASA/John Sonntag ESA

ESA