Live music: How buying concert tickets could be made better

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFans, politicians and even musicians have been complaining about the painful process of trying to buy tickets for concerts for years.

From soaring prices to intractable online queues and the prevalence of touts, everyone has a horror story.

Things came to a head last November, when the launch of Taylor Swift's Era's tour went so badly that Ticketmaster was hauled in front of the US Senate to answer questions about its business practices.

So what can be done? We asked industry experts how they would change the system.

1) Demand lower prices

Sam Nahirny

Sam NahirnyTicket prices have soared by 19% since the pandemic, and 51% of people in the UK say rising prices have stopped them attending a gig in the last five years.

The inflation has several causes: Artists are trying to combat the impact of streaming on their incomes; Brexit pushed up transport costs, as most drivers are based in Europe; and venues have passed rising electricity bills on to bands.

But some artists are taking a stand.

Pop star Caity Baser has priced her upcoming UK tour at just £11 - or "two meal deals", as she puts it - to help fans during the cost of living crisis.

"It's hard for a lot of us at the moment," she says. "I don't want a gig to be something that people can't afford.

"Growing up, I remember going to concerts after an awful week at school, and just letting loose and dancing. Then I'd go home feeling, 'Yeah, now I'm fine'.

"So if I can make it easier for people to come to a show, then of course I'm going to do that. I don't think I'd be able to enjoy myself if I knew that not everybody could have been there."

2) Eliminate queues

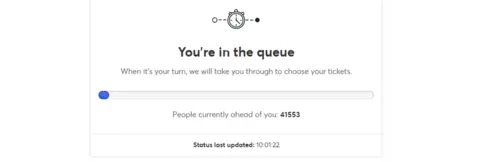

"You are in a queue. There are 38,293 people ahead of you. Do not refresh this page. Suspend all other activity. Do not use the bathroom."

Waiting rooms are infuriating, and largely unnecessary.

"The systems that are being used today were built in the 1980s and they've been barely upgraded," says Josh Katz of US ticketing start-up YellowHeart. "That's why it's so terrible.

"Snapchat has just as many users every second as [ticket websites] have when they're trying to sell tickets for an hour. Yet this old technology can't handle the volume."

UK ticketing firm Dice proves it can be done. Launched in 2014, it processes almost 500,000 sales for Spain's Primavera festival without a queuing system.

"When we originally built our [ticketing] architecture, we were obsessed with the idea of handling concurrent transactions at a massive scale and using cloud computing to handle that," says its president, Russ Tannen.

"And when we do Primavera, all the transactions are happening at the same time."

3) Be upfront about prices and availability

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLive music is inherently rare, so there'll never be enough tickets for everyone who wants to see a show.

But sometimes, there are even fewer than you'd expect. A report by New York's Attorney General found that, for one Katy Perry show at the 13,000-capacity Barclays Center, only 1,200 tickets were reserved for the general public.

The rest were held for the record label and the venue, or sold in pre-sales to credit card holders and fan club members.

"I don't think it's that pronounced in the UK," says Adam Webb of the campaign group FanFair Alliance. "Pre-sales are more like 10% to 20% of tickets. And don't forget, the aim is that those tickets go to consumers, too."

More frustrating, he says, is that ticket prices aren't revealed until they go on sale.

"When I buy a ticket to see West Ham, I know the price in advance, but that's not true for music. I don't know why."

He suggests the secrecy encourages fans to overspend, as a "panic impulse" sets in during the rush to get tickets.

"You could argue it's pressure selling."

4) Scrap hidden fees

Getty Images

Getty ImagesService fees, handling charges and delivery fees can add as much as 27% to the price of a ticket.

On Taylor Swift's Eras tour, one fan who obtained six $265 (£214) tickets found themselves with an extra $475 (£384) charge at the checkout. (NB: Venues, not artists, typically set these fees).

Experts say the fees are kept separate to make the initial price seem more reasonable, and to insulate artists from criticism.

"Fees were created to create another pile of money," analyst Bob Lefsetz recently told the LA Times. "Ticketmaster has been paid to take the heat over that for forever, so the public will never hate the act."

For its part, Ticketmaster says it wants to show customers the full price from the outset. In the UK, that's already the case, except for small handling fees at some gigs.

Elsewhere, it's waiting until everyone falls in line.

"We have seen all-in pricing adopted successfully in many countries," it said in a financial statement last year.

"This only works if all ticketing marketplaces adopt together, so that consumers truly can accurately compare as they shop for tickets."

5) Ban dynamic pricing

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDynamic pricing is a demand-based system where costs fluctuate according to how many people are trying to buy a ticket.

It made headlines in the US last year, when some seats for Bruce Springsteen's upcoming tour surged to $4,000 (£3,230).

The musician was bullish about it.

"The bottom line is, most of our tickets are totally affordable," he told Rolling Stone magazine, noting that touts routinely sold tickets for inflated prices.

"Why shouldn't that money go to the guys up there sweating three hours a night for it?'"

Ticketmaster and AXS claim dynamic pricing discourages touts, because tickets are already selling at their highest potential value.

"Over the past few years, artists and teams have lost [money] to resellers who have no investment in the event going well," Ticketmaster told the BBC.

"As such, event organisers have looked to market-based pricing to recapture that lost revenue. This is an important shift necessary to maintaining the vibrancy and creativity of the live music industry."

But ticket security consultant Reg Walker says the system "simply doesn't work" for fans.

"I don't think it's an anti-tout measure at all. Frequently, dynamically-priced tickets are more expensive than the tout's prices. You might as well just call it what it is: Price gouging."

6) Make mobile tickets the default

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's been claimed that fake and duplicate tickets contributed to the tragic crush that claimed two lives at the Brixton Academy last December.

One potential solution is to make mobile tickets the default. These typically involve a QR code that refreshes every few seconds. Only the most recent will scan at the door.

"The inability to screenshot QR codes is a very efficient security measure," says Mr Walker. When used, it has "reduced the numbers of counterfeit tickets out there to almost infinitesimally small numbers".

"We believe the method is the right one," says Stephen Lee of the Fair Ticketing Alliance. "However, the tech isn't there yet to completely roll it out to everyone, especially the elder generations."

There are lower-tech solutions, too. Every Glastonbury ticket is printed with a photo of the ticket-holder, making it impossible for anyone else to use it.

7) Make life harder for touts

Reuters

ReutersIn the UK, it has been illegal for unauthorised people to sell football tickets since 1994. But unlike France and Norway, the re-sale of live music tickets is permitted.

What is illegal is "harvesting" - using multiple identities and specialised software (known as bots) to buy dozens of tickets, then selling them for profit.

Ticketmaster says it has "invested millions in anti-bot technology every year", but it also blamed an "unprecedented" wave of bots for derailing the Taylor Swift's sales.

"This is unbelievable," said US politician Marsha Blackburn during Tuesday's Senate hearing. "Why is it that you have not developed an algorithm to sort out what is a bot and what is a consumer?"

Ticketing expert Reg Walker says most sellers "can just flick switches that stop certain types of transactions, which would probably inhibit about 90% of ticket harvesting", but they don't always use them.

"Some agents want what we call the 'Oliver Twist moment', where they sell their allocation and go back to the promoter saying, 'Please sir, can I have some more?'"

According to FanFair Alliance, that results in about 90% of the tickets on resale sites like StubHub and Viagogo being listed by professional "traders" who sell more than 100 tickets per year.

Viagogo says its own figures suggest the percentage is significantly lower.

"We absolutely agree there are a lot of problems in the industry," Live Nation's president Joe Berchtold told US Senators on Tuesday, recommending legislation as the best way to deal with bots.

However, he added, "as the leading player, we have an obligation to do better".

8) Make ticket resale more honest

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany artists, including Ed Sheeran and Adele, specify that tickets can only be resold through a platform like Twickets, where prices are capped.

Ticketmaster also introduced a ticket exchange service to the UK in 2018, allowing unwanted tickets to be passed on at their original value or less.

However, other resale sites have developed a bad reputation.

"Speculating on secondary platforms is a huge problem," says Mr Walker. "Up to 80% of the tickets listed on on some of the better-known resale platforms simply don't exist."

Stubhub and Viagogo say they will not tolerate speculative selling, and sellers who break the rules face fines and suspensions.

Mr Katz thinks blockchain technology, a form of online selling that creates a permanent record of ownership, could ultimately eradicate fakes.

"You can identify a real fan and you can identify a bad actor," he says. "Everything becomes transparent, and bad actors are eliminated."

Dice, meanwhile, only allows tickets to be exchanged on its app.

"People can join waiting lists when a show is sold out. If you have a ticket you can't use, you can return it to the waiting list and a fan can pick it up," explains Mr Tannen.

"It's a closed system that solves the problem. The tickets can't be resold."