Jeremy Hunt's Budget was more radical than it looked

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRishi Sunak started the week giving a speech on a construction site in Swindon, with diggers and cranes in the background.

So far, so typical for a prime minister in Budget week - all that was missing was for Mr Sunak to pop on a hard hat.

The diggers were knocking down the town's Honda factory, 35 years after Margaret Thatcher lured the Japanese car giant to the UK. There are hopes that the redevelopment of the site will lead to thousands of new jobs, but it is still unclear what they might be.

There are parallels with this week's Budget. Is this the start of a period of more economic growth and confident renewal? Or have several years of acute uncertainty left the economic picture permanently diminished?

The chancellor is relying on voters seeing their glasses as half-full, rather than half-empty.

Will workers celebrate paying less tax than they thought they were going to six months ago? Or decry the fact they are paying more than they were told five years ago?

Quietly radical

While the Budget lacked pre-election fireworks, there was a quietly radical thread that could have long-term consequences.

By 2027, because of cuts to National Insurance (NI) and the decision to freeze income tax thresholds, for every £1 NI cut, £1.90 will be raised in taxes.

This "fiscal drag" will mean over three million more higher-rate taxpayers, and nearly four million more low earners paying tax. On current trends, a recipient of the full basic state pension alone is also on course to have to pay tax, and perhaps fill out a tax return in 2026/27.

The government is shifting the tax burden away from workers towards all forms of income including savings and pensions.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has cast this as a strategy that could lead to the abolition of National Insurance. Mr Sunak is selling this as a simplification of the tax system, and the end of the "double taxation" of work.

Presumably, this forms the cornerstone of a manifesto promise to "end the jobs tax", and would be paid for from further extensions of the freeze on income tax thresholds.

The thinking is that these incentivise work. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which monitors the government's spending plans and performance, said levels of inactivity were back at post-pandemic levels and were holding back growth.

This is another example of the government appearing to prioritise policies that "score" with the OBR. Its chair Richard Hughes protested this week when I asked him whether he was in fact running the country. "Our only power is to forecast," he said.

Not a tax cut

According to the OBR's calculations this week's 2% NI cut and last November's 2% cut in the Autumn Statement do not offset the extra income tax being paid as a result of the tax thresholds being frozen.

But the fact that taxes on income overall are being raised means pensioners will see higher tax bills as their income increases. There is a backlash against this, but it is due to their income rising, with the state pension set to increase by 8.5% from April.

Overall this is not a tax cut, with fiscal drag equating to the biggest single tax rise in 45 years and since Mrs Thatcher's Chancellor Geoffrey Howe nearly doubled the rate of VAT in 1979.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHere is what is very curious. The Conservative strategy on tax has completely turned on its head.

Not far from the old Honda factory in Swindon, David Cameron launched his 2015 election manifesto with a commitment to raise income tax thresholds above inflation to take people out of the income tax system, and to prevent many upper-middle earners paying higher-rate tax.

It was the absolute cornerstone of Conservative tax strategy in 2017, too.

What we see now is pretty much the entire reversal of that. "U-turn" does not really capture the galactic extent of this change in direction. In 2010, there were three million higher taxpayers, by 2029 there will be 7.3 million.

Then there is another reversal - on how to fund rising public service costs. It was only three years ago that Mr Sunak was making the argument for raising spending on the NHS and social care by increasing National Insurance to 13.25%. The policy now is to decrease National Insurance to 8% and the adult social care plan is officially on ice.

Clearly, this is after a pandemic and energy crisis, and probably partly reflects the wild political ride - including four chancellors and three prime ministers in the same period of time.

'Conspiracy of silence'

Details are sparse on the precise trade-offs for unprotected areas such as councils, courts, prisons and social care. The chancellor said this was because plans are undecided and reliant on a government spending review which he has now said will not be done until after the general election.

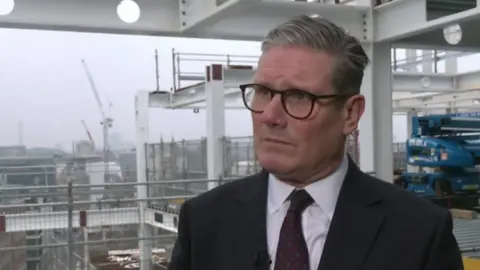

Pool

PoolLabour are also as yet unwilling to go into much detail, but leader Keir Starmer was in a hard hat meeting apprentices on a different building site in London this week, vowing to "build more houses".

An influential think tank, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, points to what it calls a "conspiracy of silence" about the tough decisions required after the election.

At the moment, Labour's promise is to fund services from higher growth, but the central plank of its growth plan, spending an extra £28bn per year on green investment, has been parked.

So the Budget may or may not herald a turnaround in the economy. But it was the confirmation of a considerable turn in economic policy, especially on who pays taxes in times of need.

From now until the election there will not be a building site in a swing seat not visited by the main party leaders dressed up in hard hats and protective goggles, as they seek to persuade the public they can rebuild the economy out of recession. But both are yet to finish construction of their long term plans to return Britain's economy to sustained growth.