Thames Water secures £750m cash injection

PA Media

PA MediaShareholders in Thames Water have agreed to provide a further £750m in funding as the company attempts to fight the threat of government control.

Thames also said it would be looking for an extra £2.5bn between 2025 and 2030.

The water firm has faced criticism over sewage discharges and leaks and is struggling under a mountain of debt.

The government has said it is ready to act in a worst case scenario if the company collapses.

Thames Water's future came under the spotlight last month when it emerged it was in talks to secure extra funding, and the firm's chief executive Sarah Bentley stepped down after just two years.

There was speculation that if Thames - which has debts of around £14bn - failed to secure fresh funds it could be temporarily taken over by the government until a new buyer is found, in a special administration regime (SAR).

This route was most recently taken with energy supplier Bulb after it ran into financial difficulties.

However, the new interim joint chief executive of Thames, Cathryn Ross, told the BBC's Today programme the company was "absolutely not" close to requiring government intervention.

She said the company had access to £4.4bn of cash and credit facilities. "That's absolutely enough to pay everything that we think we need to pay this year, next year and into the future."

However, the £750m that investors agreed to pump in to Thames between now and 2025 is less than the £1bn the company was seeking. The extra funds are also dependent on Thames improving its business plan to revive the company.

News of the extra funds came as Thames released its annual results, which showed it incurred an underlying pre-tax loss of £82.6m for the year to 31 March.

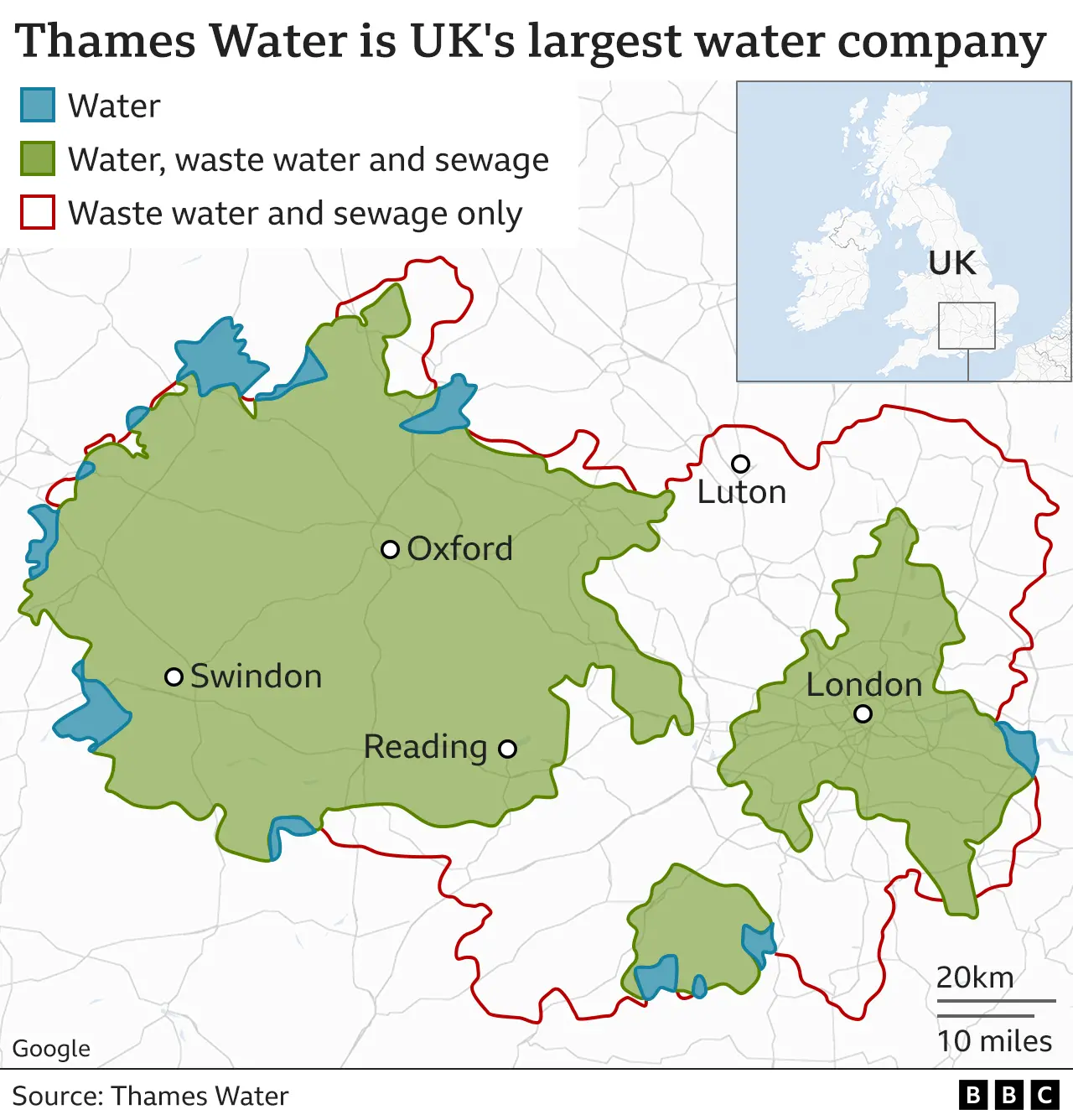

Thames Water serves a quarter of the UK's population and leaks more water than any other water company in the UK - losing the equivalent of up to 250 Olympic-sized swimming pools every day from its pipes.

Last week, Thames was fined £3.3m for discharging millions of litres of undiluted sewage into two rivers in Sussex and Surrey in 2017, killing more than 1,400 fish.

The company is owned by a group of investors. The largest is Canadian pension fund OMERS followed by the Universities Superannuation Scheme, the pension fund for UK academics.

The regulator for the water industry, Ofwat, will be questioned by MPs on Wednesday amid accusations that it has been too lax in its oversight of the sector.

At the weekend, Sir Robert Goodwill, a Conservative MP who chairs the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, told the BBC the regulator had been "very complacent" over Thames Water and had questions to answer over whether it had "been asleep at the wheel".

Last week, Ofwat chief executive David Black gave evidence to the Lords' business committee when he said Thames would need "substantial sums of money" to stabilise its finances.

He also admitted the regulator had taken a "relatively hands-off approach" to managing water companies since the industry was privatised in the late 1980s.

Thames Water's current debt amounts to 77% of the value of the business, Ms Ross told the BBC, which she said was the lowest level of indebtedness in a decade for the company.

However, Thames is the most heavily indebted of England and Wales' water companies, and interest payments on more than half of its debt rise in line with inflation, which has remained stubbornly high in recent months.

Thames Water has said that it has not paid dividends to external shareholders for the past five years.

But Sir Robert Goodwill told the BBC he suspected that Thames' holding company was taking money out in the form of debt payments, rather than as dividends.

However, Ms Ross said there was only a very small amount of debt that came from Thames' holding company.

"In the last year, we paid £45m out to service the debt that is essentially provided by our shareholders, through the holding company. Our revenues last year were £2.3bn - so you're talking about less than 2% of our revenues went to service that debt," she told the BBC.

"The vast majority of the debt that our regulated business has comes from bondholders in the open market."

Ms Ross was chief executive of Ofwat between 2013 and 2017.

She rejected a suggestion that the regulator's oversight of the water industry was affected by the potential for people to move from working at Ofwat to a potentially lucrative role in the private sector.

"I don't accept that," she told the BBC, adding that when she joined Thames Water she had spent three-and-a-half years working at telecoms company BT.

Asked if it had been her ambition to working in the industry after Ofwat, Ms Ross said: "I can honestly say the thought had never occurred to me at the time that I worked for Ofwat. In fact, I was thinking I would very much stay in the public sector at the time I was there."