Concerns over food shortages as CO2 deal ends

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUK food and drink firms say they remain concerned about supply shortages as a deal which ensured carbon dioxide (CO2) supplies comes to an end.

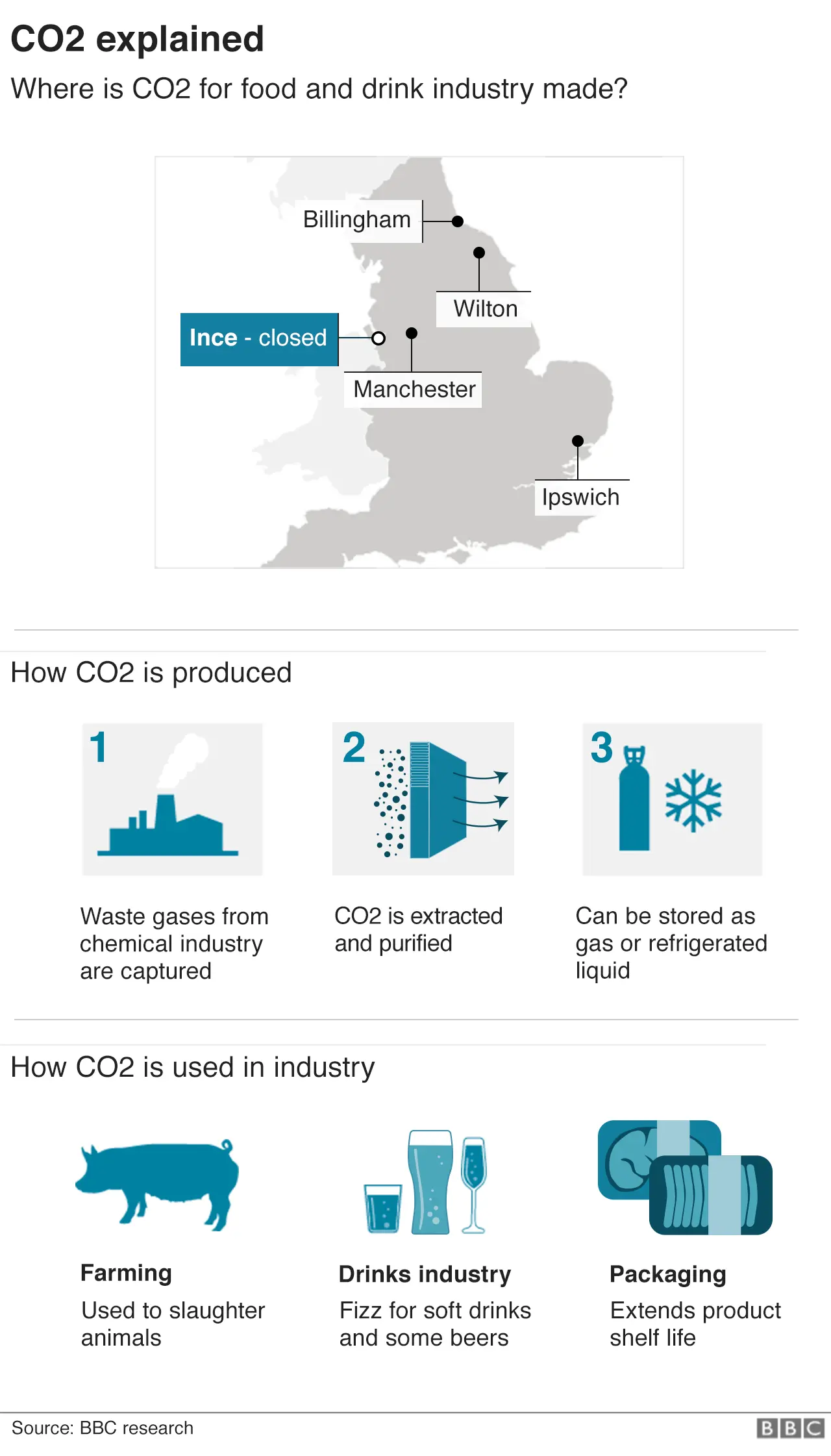

CO2 is used in fizzy drinks, to keep packaged food fresh and to stun livestock before slaughter.

CO2 users agreed a three-month deal in October to keep a key production site open after its owner said high energy prices made it too expensive to run.

The arrangement ends on Monday, raising questions over the future of supplies.

Industry body the Food and Drink Federation is warning that supermarkets could suffer shortages of some foods if the deal with US firm CF Industries is not extended.

CF Industries, which supplies 60% of the UK's industrial CO2, said it would "continue to negotiate" with its customers to "extend CO2 offtake and pricing agreements".

After previously putting up money to reopen the plant in September, and brokering the October deal, the government has said it is now up to CO2 firms to ensure continued supplies.

"We are continuing to work closely with both the hospitality and food and drink industries, and do not expect any significant disruption to essential food supplies," a spokesperson from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy said.

Last year, CF Industries temporarily shut its facilities at Ince in Cheshire and Billingham on Teessideafter fertiliser manufacturing became uneconomic because of the rising price of natural gas.

This resulted in an acute shortage of CO2. Supermarkets began reporting limited stocks of some food items, while the pig industry warned that if slaughterhouses could not process animals, then farmers would have to cull their stocks.

CF Industries reopened its Billingham plant in September after the government agreed to provide financial support to keep it running for three weeks.

The company agreed to continue supplies of gas until the end of this month -but gave no guarantees beyond that.

A Food and Drink Federation spokesperson said that with energy prices "still very high", there could be further CO2 shortages which could result in supermarket shortages that would add pressure on to families already coping with high food-price inflation.

"We will continue to work with the government on this," the Food and Drink Federation said.

"It is critical that together we ensure supply can continue and that we build long-term resilience into the production of food-grade CO2," they added.

The British Poultry Council (BPC), which represents producers of half the meat eaten in the UK, said it was "imperative" that the government continued to "honour its commitment" to food security by ensuring "little to no disruption" to supply chains in the event of a CO2 shortage.

"If CO2 continues to be actively prioritised by government for the livestock sector (along with nuclear and healthcare) on the grounds of maintaining food supply and avoiding bird welfare issues, industry can continue to keep food moving," a BPC spokesperson added.

An unusual market

The market for industrial CO2 - a pure, compressed form of the gas - is a highly unusual one, which is why this problem has been hard to fix.

Though supplies are crucial for many food and drink producers, as well as some medical procedures and the nuclear industry, it is only made as a by-product of other processes.

So if there is a disturbance to those other industries, the CO2 gets switched off as an unintended consequence. This is what happened last autumn, when the UK's two biggest sources, CF Industries and a bioethanol plant at Wilton on Teesside, were both shut down at once.

Fixing the problem has proved tricky. Industrial CO2 is difficult to transport and store, and it is difficult to import much more because there are shortages across Europe. In addition, new production facilities cannot be opened in three months.

Tony Will, chief executive of CF Industries, told the Financial Times in September he was "as surprised as anyone" to learn how crucial the CO2 he sold was to UK industries.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnalysis

By Ben King, business reporter

CF Industries keeps its cards close to its chest.

But this winter it might be easier for them to justify keeping the crucial plant at Billingham open, even though gas prices remain high.

The CO2 it produces, so vital to so many industries, is made as a by-product from producing ammonia, a chemical used in fertiliser manufacture and other industrial processes.

And it's a great time to be making ammonia.

World ammonia prices have surged since September, when the government reached into its pocket to convince CF Industries to turn Billingham back on.

The global benchmark price, CFR Tampa, has almost doubled to a record high of $1,135 a tonne this month, according to market data provider Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS).

And if war disrupts the 20% of global supply which comes from Russia and Ukraine, prices could go higher still.

"If I was an ammonia producer at the moment, I would want to keep on producing," said Richard Ewing, who watches the ammonia market at ICIS.

But only CF Industries will know if this is enough to keep Billingham open.