The student loan bubble 'is going to burst'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCancelling student debt was once a fringe idea in the US, but as loans mount, it's become increasingly mainstream.

For her birthday this year, Alicia Davis received one of the best gifts ever: word that roughly $20,000 (£14,500) of her student debt would be erased.

It's a massive relief, resolving an issue that has drawn threats from debt collectors, raised questions in job interviews and ruined her credit, making it difficult to do things like buy a car.

"This is the best birthday present," the 38-year-old recalls thinking. "I'm able to function in society now."

The forgiveness came after the Department of Education in March agreed to fully cancel debts from borrowers, like Alicia, who had proven to officials that their schools had misled them about things like cost and employment prospects.

The move was among a series of steps the Biden administration has taken to address America's rapidly mounting student debt, which hit $1.7 trillion (£1.2tn) last year. But he faces pressure from his party to do far more.

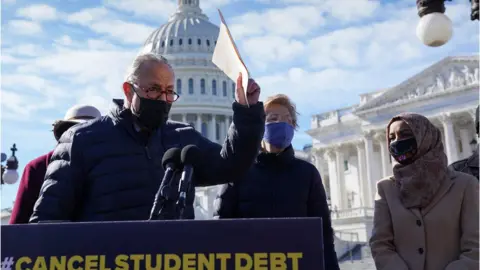

Reuters

ReutersTop Democrats, including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, have called on the president to use his power to wipe out borrower debts up to $50,000.

The proposal would completely eliminate debts for more than 34 million people and could cost as much as $1tn by some estimates - as much as the country has spent on housing assistance over two decades.

For Washington, the embrace of such demands marks a striking change, as an idea advanced by anti-corporate greed Occupy Wall Street activists a decade ago - and resoundingly rejected by the Trump administration - moves to the heart of political debate.

"It's an issue that has really reached a critical moment where it just cannot persist as it has any longer," says Persis Yu, director of the Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project at the National Consumer Law Center.

"The fact that widespread cancellation has gained so much momentum and is now more of a mainstream idea is an acknowledgement of that crisis."

How did the US get to this point?

More than 42 million people in the US - roughly one in six adults - hold student debt, which averages roughly $30,000 for a four-year undergraduate degree.

Financial stress from the loans, which bring typical monthly bills of nearly $400 for recent graduates, has been blamed for holding back a generation financially.

Nearly a fifth of borrowers are in default and millions more are behind on payments, which come due shortly after graduation regardless of employment or income.

The government, which owns more than 90% of the debts, estimates that roughly a third will never get repaid.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrevious efforts to address the issue have focused on borrowers who were misled by for-profit universities about fees and job prospects.

The US has also tried to expand programmes that reduce debts for people in certain public service jobs, or tie repayment to income - moving closer to a system like that in the UK, where the average debt load is higher and the government expects more losses, but borrowers are better shielded from issues like default.

But widespread problems with actually accessing the US programmes have led to demands for broader, more immediate loan forgiveness, in addition to other reforms.

"We need widespread debt cancellation of some amount to help clear the books," says Ms Yu, whose organisation recently obtained federal data that showed that just 32 people had actually had their debts forgiven via income-driven repayment plans.

"It's really hard to discern who deserves relief and who doesn't," she adds. "If you want to start slicing and dicing who is entitled to relief, I assure you folks who need it won't get it."

'Our system is broken'

Alicia says she's an example of how big the problem is. She won the $20,000 debt discharge after years of fighting over loans she took out when she enrolled in a for-profit Florida college in 2006, hoping to launch a career in law enforcement.

Two years in, she says the school stopped communicating with her.

"It didn't seem right that I would pay all this money and have nothing to show for it," says Alicia, who joined the student loan advocacy group Debt Collective and filed claims with the government, ultimately suing to force action.

But even after winning that battle, she still faces the prospect of decades of bills to repay the further $75,000 she took on to finally earn her masters degree from a public university while working as a bartender.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I'm not paying for something that was a scam but I'll still have tonnes of debt," says Alicia, now a private intelligence analyst.

"Our system is broken," she adds. "It's to the point now where it's like the housing bubble - it's going to burst. You can only milk people so much before they just give up."

'Fundamentally unfair'?

President Biden has backed forgiveness of up to $10,000 in debt - a proposal analysts estimate would affect about a quarter of outstanding debt, or more than $400bn, and completely eliminate burdens for more than 15 million people.

But he has rejected the calls to waive up to $50,000.

"I will not make that happen," he said at a town hall earlier this year, arguing that such a move would benefit graduates of elite professional schools, like doctors and lawyers, and the money would be better spent, for instance, on lowering tuition costs.

His resistance reflects voter concerns.

In a February Harris poll of roughly 1,000 adults, just 46% of people said they supported some level of debt forgiveness, down from two months earlier. Republicans have also consistently opposed widespread debt relief.

"It's fundamentally unfair to ask two-thirds of Americans who don't go to college to pay the bills for the mere one third who do," Donald Trump's Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said in a speech last year.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAdvocates say they remain hopeful that Mr Biden will act, noting that the issue is especially important to young voters and ethnic minority communities, who were key to his election victory.

They say they have been encouraged by steps he has taken that would clear the way for forgiveness to occur, such as asking for a formal legal opinion about his powers to do so without Congress, and that he should seize the chance for reform while student loan payments are on hold due to the pandemic.

"You have this once-in-a-generation opportunity to actually fix things before people have to start paying their bills again," says Mike Pierce, director of policy at the Student Borrower Protection Center.

"It's going to be a test of this administration's political will whether they can actually get the job done."