The tax that hits struggling High Streets hardest

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFinding a new retailer for a prime spot in Blackpool town centre used to be easy.

In the 1980s and 1990s, firms would have been fighting over the keys to 18-22 Victoria Street, a large, modern two-storey unit directly opposite the shopping centre. Not any more.

Until last month, the property had been rented to Topshop and Topman. But their owner, Sir Philip Green's Arcadia group, walked away when the lease came up for renewal. His shops have been struggling to keep up with the competition, and dozens, up and down the country, are being closed.

"We are having difficulty attracting any interest, never mind a national retailer," says Paul Moran, a ratings surveyor whose company, Mason Owen, is tasked with finding a new tenant.

Business rates, he says, were a factor in Arcadia's decision to pull out, and they're now a big barrier to someone else moving in.

"The first thing tenants look at are their outgoings. And when they see the rates bill, they will be put off by that. Normally you'd expect to be paying 50% of your rent in rates, but the rates bill in this shop is dramatically higher than that."

With retail in turmoil, pressure is growing for change. So what are business rates and why are they a problem?

Business rates are a kind of council tax for commercial property. All sorts of premises have to pay them, from offices, warehouses and pubs, to power plants, train stations and shops.

Bills are worked out based on the government's estimate of how much the property would cost to rent on the open market. Businesses have to pay the tax regardless of whether the space makes any profit or not.

As a rule of thumb, your business rates bill is now typically half of your rent. That's a big financial burden in itself for retailers with lots of shops. But many of our national chains aren't even being charged the right amount to begin with. They're paying millions of pounds more in rates than their rents would imply.

Properties get revalued every few years by the government to make sure the occupiers are paying the correct sums. Some bills go up and some go down. The last revaluation was in 2017.

For towns like Blackpool, this should have been good news because retail rents had collapsed. Their business rates bills should have dived as a result, bringing some relief to a town grappling with too many empty shops and years of government austerity.

But here's the problem. Changes in bills, both up and down, are phased in gradually over several years to help businesses adjust. It's like a shock absorber, and it's called "transitional relief".

The system is good news if your bills are going up, but not so good if you're in a property due a big reduction. It's a bit like being told you're due a tax cut, but your bill will only be cut incrementally over five years, and you may never get the full reduction.

It works like this because the government wants to make sure it receives the same amount in business rates in real terms, or adjusting for inflation, each year. So rate rises and decreases must balance. This is an England-only policy.

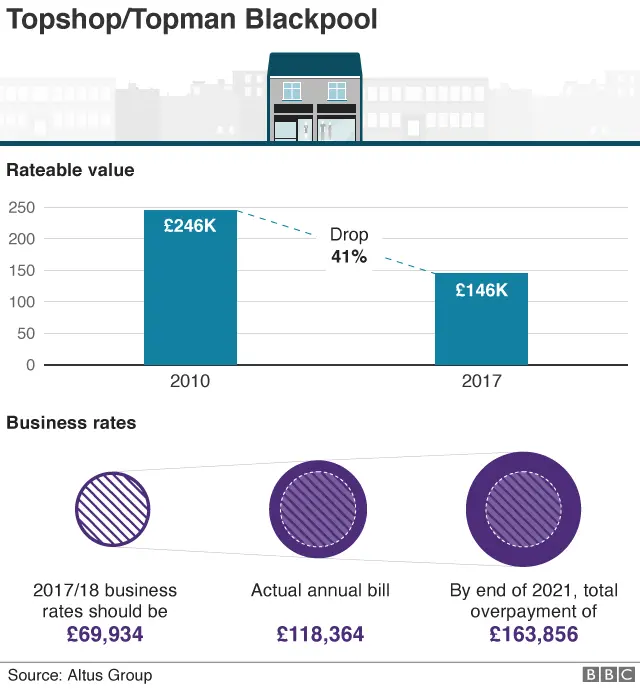

And it's the largest stores occupied by big chains that are the most affected. Blackpool's 18-22 Victoria Street is a good example.

Back in 2010, this property was valued at £246,000. Remember, this is the equivalent of what it could be rented for. By 2017, this had dropped to £146,000. This fall should have produced a business rates bill that year of £69,934. The actual bill was £118,364.

"The annual business rates bill for this property today is still £112,000," says Mason Owen's Paul Moran.

"I've been involved in ratings valuations for 40 years. But I've not seen a situation where the actual liability for a shop is so out of line with the… rental value in locations like Blackpool. It's unsustainable."

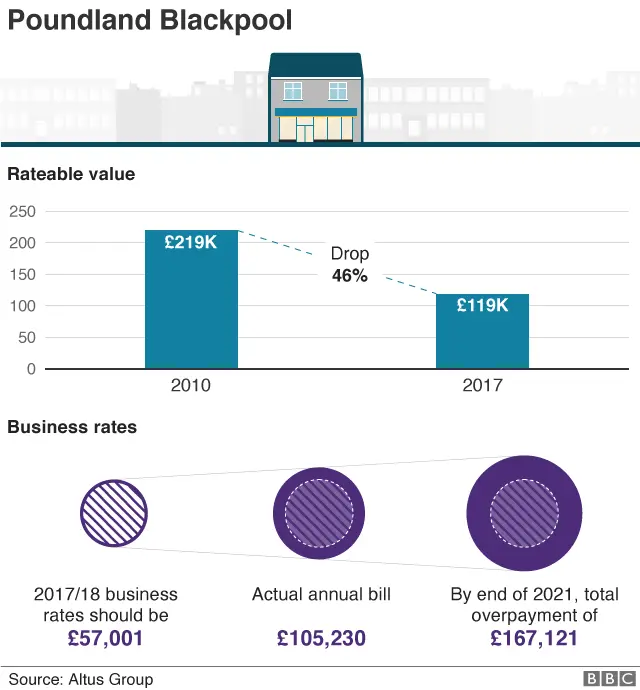

Down the road is Poundland, and its business rates numbers are even more striking. Its business rates bill should have dropped by 46% between 2010 and 2017. Instead it will only have gone down in real terms by 13% by the next revaluation next year.

According to Altus Group, a ratings advisory company, this one store is effectively paying £167,121 more in rates than it should.

Poundland isn't struggling - far from it. Unlike a lot of other retailers, it's still managing to grow sales in its physical stores. It has 850 shops in the UK and Ireland and is interested in opening more. Still, its UK and Ireland boss, Barry Williams, says transitional relief is costing his business millions of pounds.

"Transitional relief? I call it comic relief. It needs to be scrapped," he says.

"I could open more shops. I could employ more colleagues. I could create better products. It just holds the business back from investing and from driving growth. It makes us question certain sites that we'd move into and for many of our competitors it means they are actually closing stores," he says.

The crisis on our High Streets was a big issue on the doorstep during December's general election. The new government, which is on a mission to "level up" regional inequalities, is spending about £3.6bn to revitalise struggling town centres. But at the same time, many of these places are the hardest hit by transitional relief.

"The phasing in of very large tax rises is a good thing when there are big upward shifts in property values. The big question is how you pay for that," says Robert Hayton, head of UK business rates at Altus Group.

"A very small supplement on all bills would spread the burden. But taking from those local economies that have struggled isn't the answer. It affords them no respite to recover and rebuild and certainly doesn't aid the levelling up of prosperity."

The leader of Blackpool Council says rates bills just need to match current rents.

"There is some £7m which isn't in our pockets because it's going elsewhere, and that is always the complexity of a tariff and top-up system. There is an unfairness inherent in the whole system. It's outdated," says Councillor Simon Blackburn.

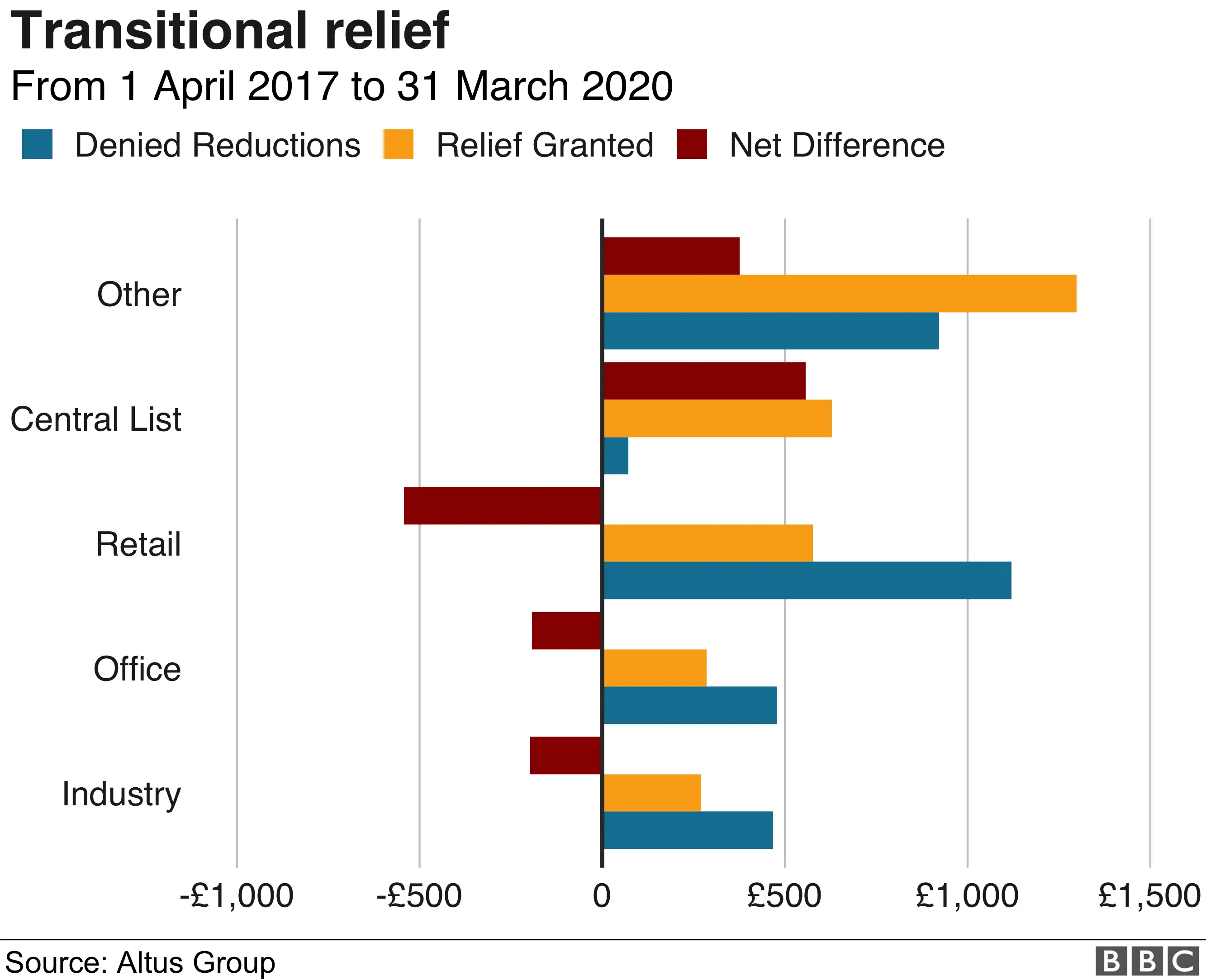

There are always individual winners and losers with business rates. It's the way this tax works - the burden is redistributed when one area becomes better off relative to another. But if you take a deep dive into the numbers, there are also winners and losers in different parts of our economy.

The chart below is based on the government's own numbers, which show how much each sector has been granted in relief to phase in large increases, as well as the amount of tax reductions that have been held back. The biggest winner is the Central List, which includes some of Britain's biggest private infrastructure companies, such as utility firms and telecommunication providers.

"Other" is basically everything else that isn't office, industrial or retail businesses. It covers public sector buildings like schools and hospitals (which are required to pay business rates), as well as leisure and hospitality.

The losers are those sectors on the left, and the biggest one is retail. Over the past three years this sector has paid an extra £543m because of transitional relief.

"Retailers are paying a disproportionate slice of the UK's business rates bills, and this burden is based purely on the size and value of their properties, no matter how well their businesses are doing," says John Webber, head of ratings at Colliers International. "Not only that, they are being clobbered by transitional relief."

You can understand why the government has been reluctant to meddle with this system of taxation. Business rates generated £25bn for HM Treasury in England alone this financial year, according to Altus. The tax is also easy to collect and difficult to avoid.

The government has promised a fundamental review of business rates and will halve rates for small shops from April.

"Since 2016 we've cut business rates across the board, with reforms that will reduce their cost by £13bn over the next five years," says a Treasury spokesperson.

It's worth pointing out that a lot of smaller, independent retailers don't pay any rates. That's because if a business's property is deemed to be worth less than £12,000, it is eligible for 100% relief. It's bigger stores that have a rateable value of more than £51,000, and get no government help, that pay 70% of the sector's overall rates bill.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, it isn't business rates which are hurting the High Street, but competition from online. It says abolishing rates, for instance, would largely lead to higher shop rents.

But one experienced retail property investor argues this view misses the point.

"Yes, some rents would potentially go up if you reduce rates… but this isn't a normal market any more," says Mark Williams of RivingtonHark, which invests in and manages a range of town centre properties.

"There's a huge structural change going on, and there are many examples where landlords are subsidising the rates payable by the occupier simply to try and let space."

In Nuneaton, for example, the local council charges Poundland just £1 each year to rent a store in a shopping centre it owns because it is desperate to attract tenants. The business rates bill is £117,000.

Reforming business rates won't stop the huge shift to online shopping and the need for fewer shops, which are the big challenges for UK retailers. In other words, there's too much retail space and not enough demand.

While business rates are never the sole reason for a retailer shutting up shop, it does feel like the tax is out of kilter with the seismic changes taking place on the High Street.

More frequent revaluations would help. And this is something the government is introducing from April next year when revaluations will move to every three years from the standard five-year period.

The clock is ticking. The next period for bills is set to begin in April 2021. If transitional relief isn't sorted by then, John Webber of Colliers says the problem is going to get even worse.

"We will see an increasing number of empty shops because retailers will no longer be able to afford to stay in the same number of physical units," he says.