China's economic slowdown: How bad is it?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChina's economy has been slowing for the better part of the past decade, but a recent run of poor data has prompted fresh concerns. What is making investors nervous, and how China has responded?

China became a key engine of world economic growth as developed countries licked their wounds after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Now, the world's second-largest economy is expanding at its slowest pace since the early 1990s.

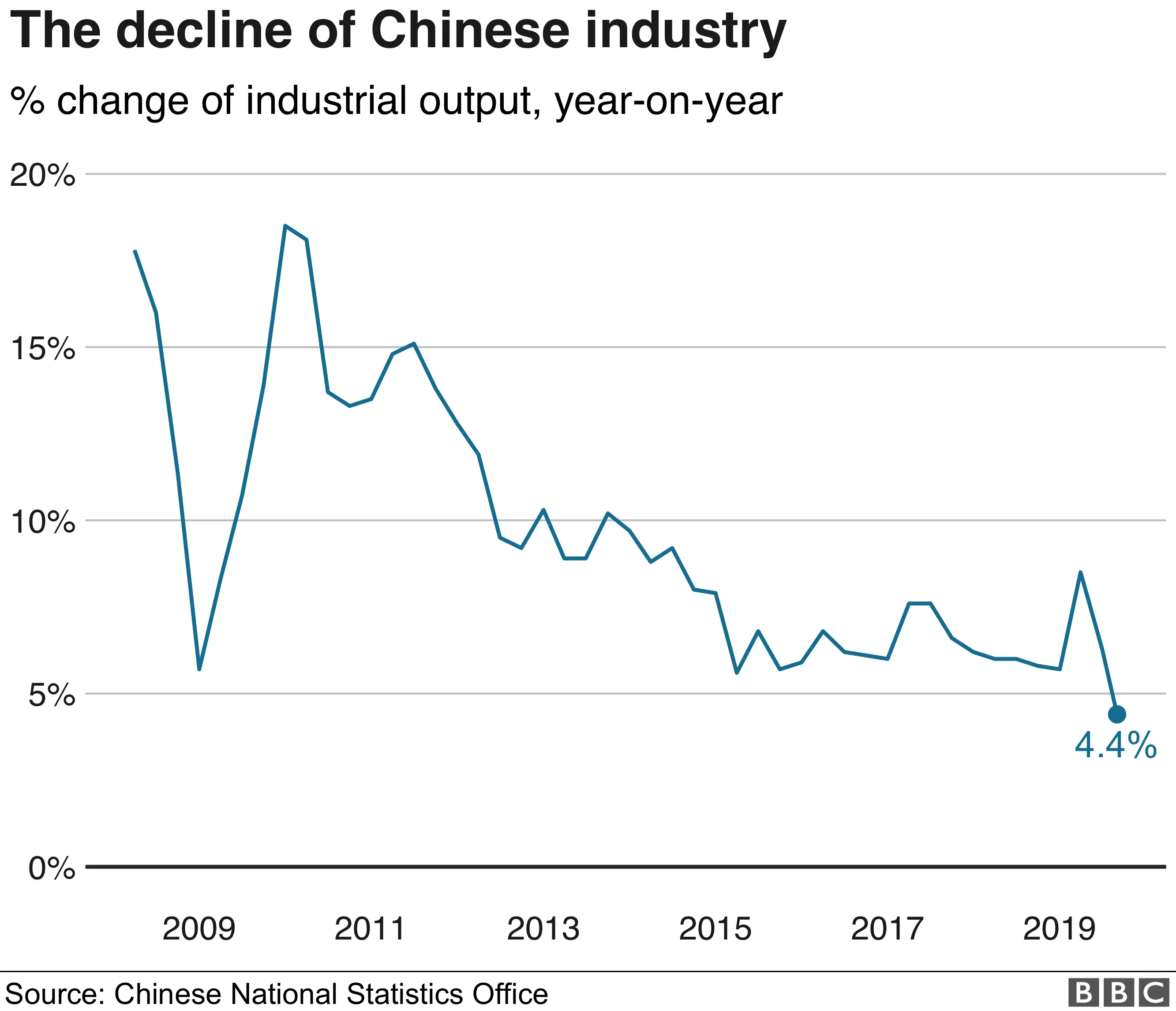

China saw industrial output grow at its slowest pace since 2002 in August.

Weeks later China's Premier Li Keqiang said it would not be easy for the country to sustain growth rates of above 6%.

Domestic issues, the US-led trade war, and swine fever are all putting a brake on China's rapid expansion.

"The slowdown in China is becoming quite significant," says Tommy Wu, senior Asia economist at Oxford Economics.

"Both the weakening in the domestic economy and deteriorating external environment, including both a global slowdown, and the US-China trade tensions, have a role to play in China's slowdown."

Given China's importance in the global economy, and its healthy demand for anything from commodities to machinery, any downturn is likely to have far-reaching consequences.

Gary Hufbauer, of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, estimates that a one percentage point drop in Chinese growth would probably take 0.2 percentage points off global growth.

What is happening in China?

The official data paints an increasingly cloudy outlook.

Industrial output is growing at its weakest pace since 2002, and retail sales are slowing.

Getty Images

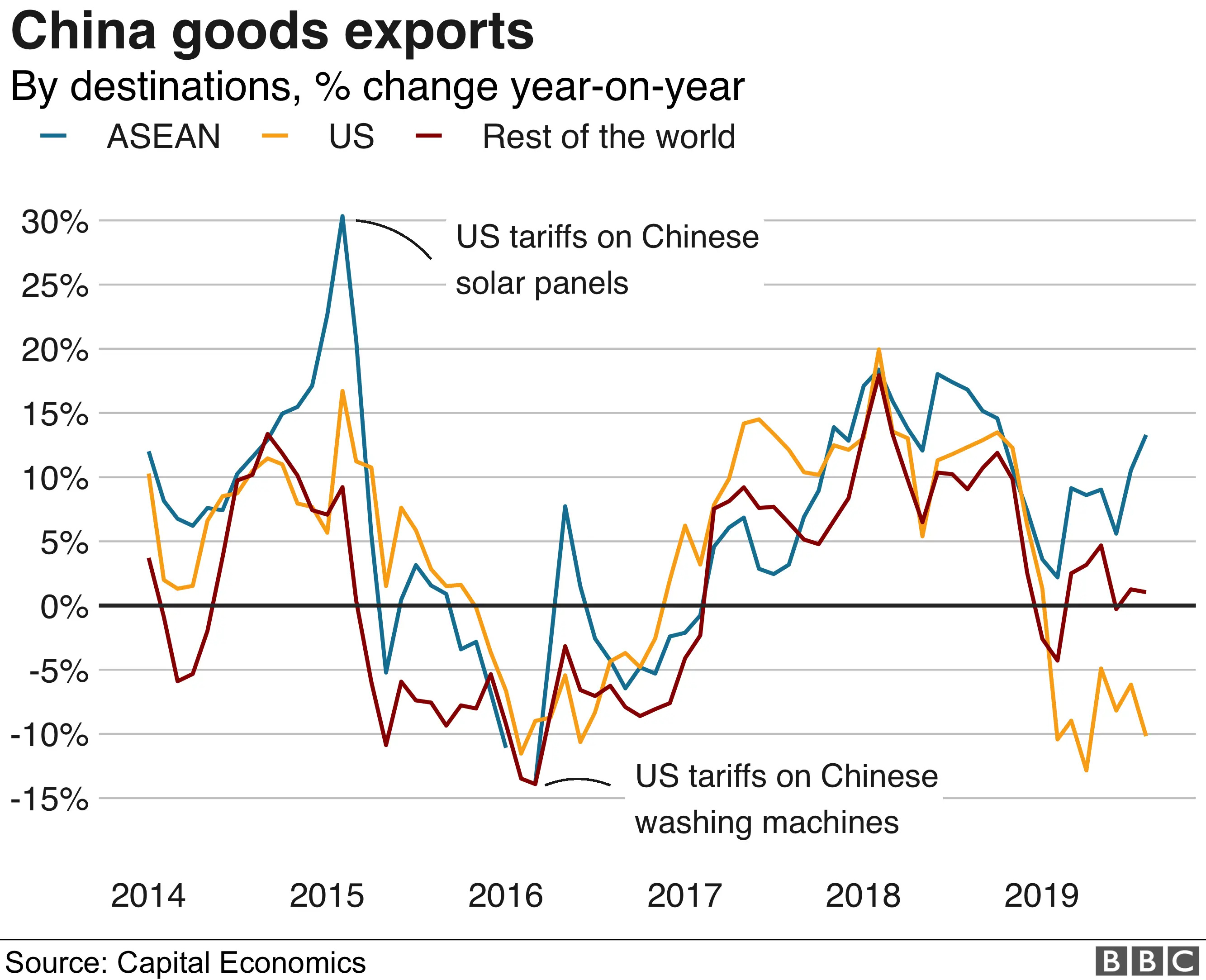

Getty ImagesChinese exports fell in August by 1% from a year earlier, and by a sharp 16% to the US - a clear sign that the dispute with the US is hurting bilateral trade.

But while growth is down from double digit levels in the mid-2000's, the more recent slowdown has been relatively gradual.

China's economy grew 6.2% year-on-year in the second quarter, easing from 6.4% in the first three months of the year, and from 6.6% in 2018.

"It's not as if Chinese growth has completely fallen off a cliff," says Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economics research at HSBC.

"On the contrary, there are still many pockets of growth," he adds, pointing to housing construction and spending in the services sector.

How effective has stimulus been?

China's government has sought to support the economy this year through tax cuts, and by taking measures to boost liquidity in the financial system.

But Mr Neumann says that this time around, the government was being "fairly restrained" when providing credit to firms and individuals, and administering stimulus.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat's because the government believes China needs to curb the risk in its financial system, and cool the rapid credit growth of recent years, he adds.

"Chinese authorities are not really showing signs of wavering from this track... so it's by design in many ways, rather than by accident, that we've seen weaker economic growth numbers," says Mr Neumann.

Having relied heavily on infrastructure spending to stimulate the economy over the years, analysts say Beijing had limited room to do much more on that front.

Instead they have opted for tax cuts, which tend to be less effective in boosting growth than infrastructure spending, says Mr Wu.

Mr Wu expected Beijing to do more to stimulate the economy going forward - both through fiscal and monetary policy - but worried this would not be enough.

"We do expect more to come to help stabilise growth by next year. But the key downside risk is that the authorities do not step up policy support enough to stabilise growth."

What has been the fallout from the trade war?

The US and China have been fighting a trade war for more than a year, and more tariffs are expected.

The impact from the US tariffs has been offset to some extent by a weaker yuan, says Julian Evans-Pritchard at Capital Economics, while China has also sought to bypass the taxes by exporting to the US via other Asian countries.

He says that China's share of global exports has actually grown over the past year, showing that the fall in Chinese exports has been less pronounced than those from other countries.

Western businesses, meanwhile, are finding it increasingly hard to navigate the uncertainty.

Some have been shifting production out of China, even though the numbers have not been large enough to show up in the economic data, says Mr Evans-Pritchard.

"The longer these tariffs remain in place, the longer this drags on, the higher the chance we are going to see more firms shifting out of China, and it also makes the country a less attractive place to invest in the first place," he says.

While many firms will want to keep some production in China to cater for its important domestic market, there are signs some firms are already considering their options.

According to a 2019 survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, 65% of members said trade tensions are influencing their longer-term business strategies. Nearly a fourth of all respondents are delaying China investments, it said.

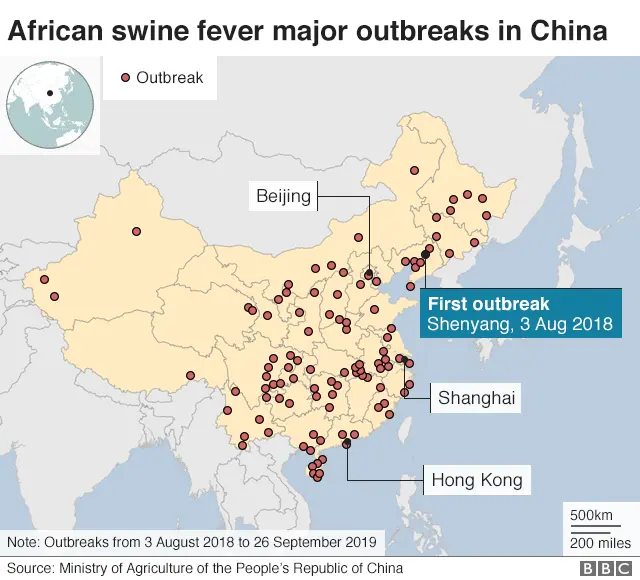

How about the swine fever outbreak?

The deadly swine fever has placed an additional drag on the Chinese economy over the past year.

China, the world's biggest producer of pork, has struggled to control the disease even after slaughtering more than one million pigs.

The supply shortage has sent pork prices soaring - by 46.7% in August on a year earlier- and that is eating into household incomes.

Global Trade

"The price of pork has almost doubled," said the Peterson Institute's Hufbauer, adding that this was "very painful for low income Chinese."

Pork is one of China's main food staples, and accounts for more than 60% of the country's meat consumption.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile for now the surge has been partly offset by more subdued non-food inflation, analysts say this could quickly change.

"What worries me is that they just don't seem to have gotten the disease under control yet. The pig stock is still falling," says Mr Evans-Pritchard.

"At this stage it's already pointing towards pork price inflation rising above 80% year-on-year within the next six months."