Is this America's most hated family?

Eyevine/Shutterstock

Eyevine/ShutterstockYou might never have heard of the Sackler family but you may well have enjoyed their money.

The Anglo-American billionaire dynasty are prolific philanthropists and some of Britain's best-known art galleries, museums, theatres and universities have benefited from their generosity.

But behind the money is a firm called Purdue Pharma, a US company owned by many of the Sacklers which makes opioids - a class of drugs linked to the deaths of thousands of Americans.

Now, some in the arts say they don't want the Sacklers' money anymore.

This week alone, the Tate said it would no longer take funds from the family while the National Portrait Gallery and the Sackler Trust said they would not proceed with a £1m donation.

And in New York, the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, which has received a total of $9m (£6.8m) from the Sacklers, said it did not plan to accept any more gifts from the family

Who are the Sacklers?

The family's fortune, estimated at $13bn by Forbes magazine, was started by three brothers from Brooklyn, New York.

Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler were all doctors and in the early 1950s they bought a medicine company called Purdue Frederick which would become Purdue Pharma.

Alamy Stock Photo

Alamy Stock PhotoEach of the brothers owned a third of the firm but when Arthur Sackler died in 1987, Mortimer and Raymond bought out his stake.

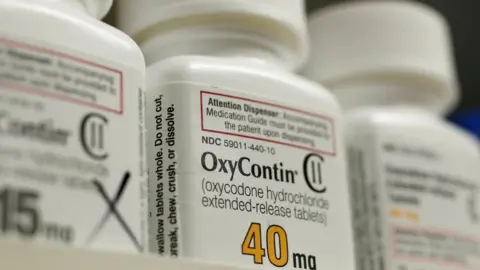

Purdue Pharma went on to invent OxyContin, a prescription painkiller with a slow release formula which hit the US market in 1996.

Much of the Sackler family's fortune comes from Purdue Pharma.

Thanks to the billions generated by Purdue and donated by the Sacklers, the family name can be found adorning a wing of the Louvre in Paris, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as well as the V&A, the Serpentine and Shakespeare's Globe in London among many, many others.

But Andrew Kolodny, co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, describes the philanthropy as "reputation laundering".

"That's what they were doing with all of this money they were giving to museums and to universities," he says. "Their wealth was earned through the sales of a drug similar to heroin.'"

A spokesperson for Sackler family members said, "For more than half a century, several generations of Sacklers have supported respected institutions that play crucial roles in health, research, education, the arts and the humanities. It has been a privilege to support the vital work of these organizations and we remain dedicated to doing so.

"While plaintiffs' court filings have created an erroneous picture and resulted in unwarranted criticism, we remain committed to playing a substantive role in addressing this complex public health crisis.

"Our hearts go out to those affected by drug abuse or addiction."

Reuters

ReutersRaymond Sackler died in 2017.

His son Richard, who is known within Purdue as Dr Richard, was chairman and president of Purdue.

Others involved or have been with Purdue are Raymond Sackler's wife Beverly, their other son Jonathan and Raymond Sackler's grandson David.

Mortimer, who was awarded an honorary knighthood by the Queen, died in 2010.

His wife Dame Theresa Sackler - a trustee of the V&A - has been a board member at Purdue as have Mortimer's daughters Ilene Sackler Lefcourt and Kathe Sackler and son Mortimer Sackler.

What is the issue?

Purdue Pharma is facing hundreds and hundreds of lawsuits because of OxyContin.

The company is one of a number opioid manufacturers and distributors who are accused of using misleading marketing about the drug and downplaying concerns about abuse and addiction to encourage doctors to prescribe more of it.

Purdue Pharma strongly denies the claims.

Dr Kolodny says that opioids had mostly been used to treat people with cancer, for end of life care or after surgery for a limited time.

He says: "There wasn't very much money to be made if OxyContin had only been prescribed to people at the end of life with cancer because end of life cancer pain is not that common and people won't be on your drug for very long at the end of life.

"So the way you can do well with a pharmaceutical product is if doctors prescribe it for common problems like lower back pain or headaches. If you have a drug that is difficult to stop taking you've got a pretty good recipe for financial success."

With prescription opiods in more bathroom cabinets across America, family members were becoming exposed.

Dr Kolodny says that for people in their 20s, who may have tried a prescription opioid "for fun" and become hooked, it was difficult for them to get more off a doctor because they looked healthy.

"The pills on the street, even in 2001 were very expensive, he says. "So young white people in the US in their 20s and 30s started switching from pills to heroin."

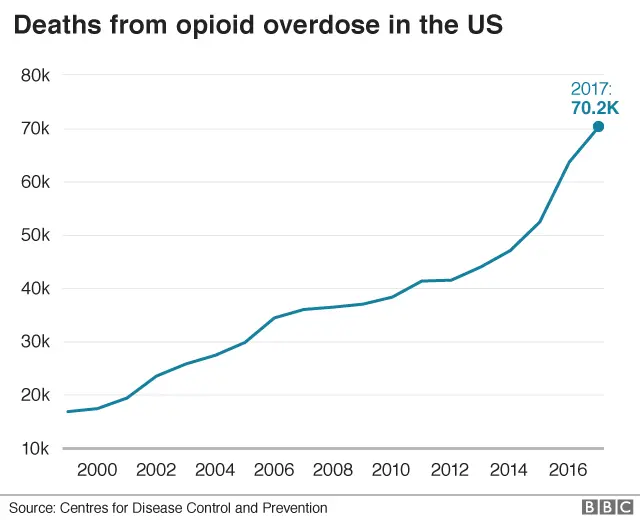

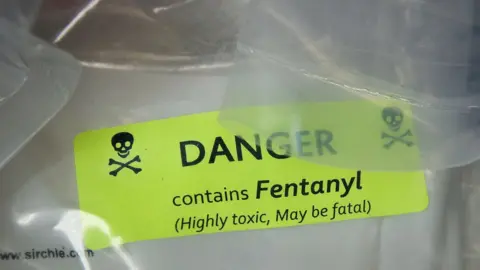

With powerful opioids like Fentanyl entering the illegal drugs market, the risk of overdose increased.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith Fentanyl, the opioid epidemic which the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says began with prescription painkillers then heroin, is now in its third wave.

Purdue says that OxyContin "constitutes an exceedingly small per cent of the prescription opioids prescribed in the US" which it says is less than 2%.

Dr Kolodny says: "Certainly there were other drug companies that saw how well this was working out for Purdue and got into it early on as well."

But he claims: "Purdue got the ball rolling."

What's behind the Tate and National Portrait Gallery's decision?

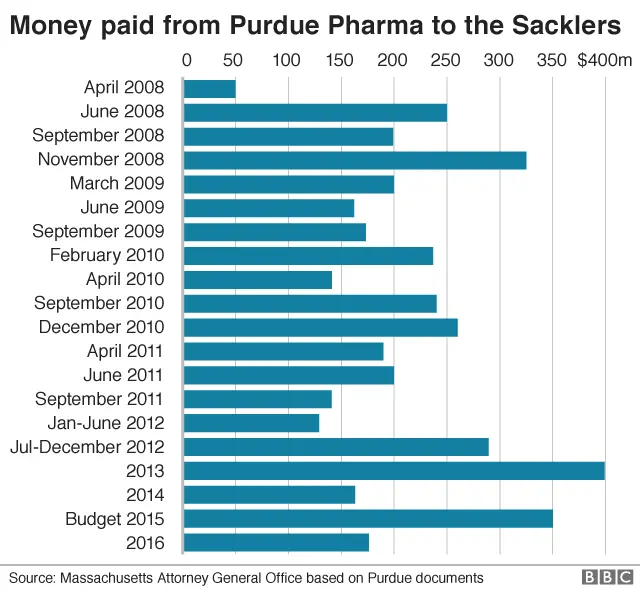

Among the lawsuits facing Purdue are some that name members of the Sackler family.

In particular, the complaint by Massachusetts Attorney General, Maura Healey, recently released a number of potentially damning documents and alleges that "they directed deceptive sales and marketing practices deep within Purdue".

It paints the Sacklers as forceful board members, intent on pushing Purdue Pharma's salesforce to persuade doctors to prescribe more and more OxyContin at higher doses to their patients.

EThamPhoto / Alamy Stock Photo

EThamPhoto / Alamy Stock PhotoIt also presents Richard Sackler as someone who does not view OxyContin as contributing to opioid addiction, instead blaming the individuals themselves.

In an email included the Massachusetts complaint, Richard Sackler wrote: "We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible. They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals."

Purdue Pharma forcefully denies the claims made in the lawsuit and has filed a motion to have the lawsuit dismissed. It says it is "is replete with sensational and inflammatory allegations" and is "oversimplified scapegoating based on a distorted account of the facts unsupported by applicable law".

Where now for Purdue and the Sacklers?

This week in the US, the House Oversight Committee said it is seeking information from Purdue about which Sacklers sat on the board as well as documents detailing marketing strategies for selling OxyContin.

There has also been speculation that Purdue Pharma may filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy which would automatically stay all litigation against the company and allow the firm to be reorganised.

For the some of the people who have been campaigning against the Sacklers, announcements by the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery are "very welcome".

LA Kauffman, an activist and author who is a member of Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, a group started by US photographer. Nan Goldin who became dependent on OxyContin, says it is a sign "the tide is really turning".

But she says while it is important to "acknowledge that this was a bold step for institutions to take", she asks; "If museums don't stand for the basic value of human life what do they stand for?"