Opioids: Why 'dangerous' drugs are still being used to treat pain

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe widespread use of opioids to treat pain frequently prompts concerns about addiction and even deaths. So, why are these sometimes dangerous drugs still being given to patients?

Much stronger than many of the other options, opioids are among the world's most commonly prescribed painkillers.

These drugs - including morphine, tramadol and fentanyl - are used to treat pain caused by everything from heart attacks to cancer.

But in the UK they were recently linked to the deaths of hundreds of elderly hospital patients, while the US is battling a well-documented opioid epidemic.

Why not just use other painkillers to avoid the risk of harm?

A worldwide problem

Opioids work by combining with receptors in the brain to reduce the sensation of pain - and they are highly effective.

However, opioid receptors are present in areas of the brain responsible for breath control and high doses can dangerously reduce the rate of breathing - the cause of almost all opioid deaths.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn inquiry into the UK's Gosport War Memorial Hospital said more than 450 people died between 1989 and 2000 from administration of "dangerous" amounts of opioids without medical justification.

In the US, the increasingly widespread prescription of opioids to treat long-term pain has led to an epidemic of addiction. In 2016, a record 11.5 million people in the US misused prescription opioids, and there were 42,249 deaths from overdoses.

In England, GPs prescribed 23.8 million opioid-based painkillers in 2017 - a rise of 10 million prescriptions since 2007. More than 2 million working-age people were thought to have taken a prescription painkiller that was not prescribed for them in 2016-17.

There were more than 2,000 deaths in England related to opioid overdose in 2016, the highest since records began. But unlike the US deaths, these largely related to heroin rather than forms of opioid available on prescription.

What are opioids?

- A large group of drugs used mainly to treat pain

- Includes naturally occurring chemicals like morphine and codeine, as well as synthetic drugs

- Codeine, morphine and methadone are among opioids judged by the World Health Organization as essential for treatment of pain and end-of-life care

- Some opioid medications - methadone and buprenorphine - are used to help people break their addictions to stronger opioids like heroin

Consistent relief

One of the reasons opioids are so widely used is that - when used correctly - they are a particularly useful form of painkiller. They can be given to patients in a variety of ways and in many different forms.

Morphine can be given orally or through injection; other opioids can be given through patches, lozenges or under-the-tongue tablets.

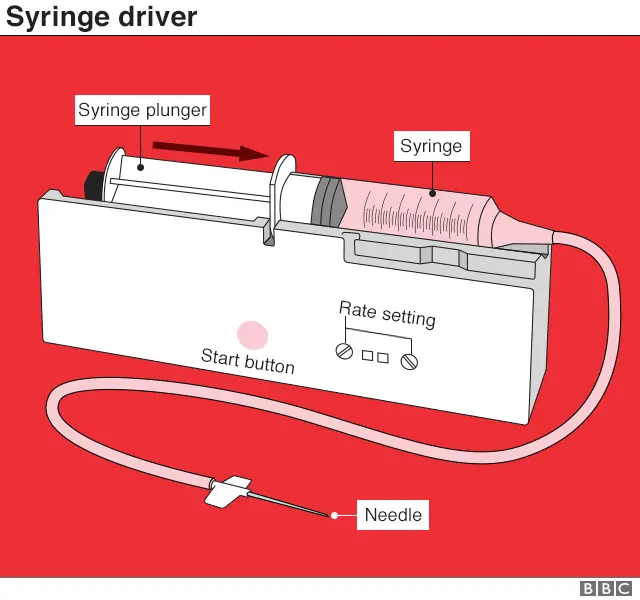

The Gosport report focused on syringe drivers, a method of delivering a drug under the skin, to provide a constant dose of an opioid for consistent pain relief.

This can be a useful form of pain relief at the end of someone's life as it means there is no reliance on the patient being able to swallow or absorb the drug. Syringe drivers also help doctors adjust dosage as necessary.

However, at Gosport War Memorial Hospital, syringe drivers were reportedly used when they weren't justified, or to deliver inappropriately high doses of opioid.

A distressing reaction

Despite their benefits, the problems associated with these medicines are clear.

For decades, scientists have tried to develop opioids that work without causing the problems of addiction and misuse.

Some have added extra ingredients deliberately to cause a distressing reaction. For example, added to opioid tablets, the antidote naloxone largely has no side-effects if the medication is taken orally, but causes severe "cold turkey" withdrawal symptoms if the tablet is crushed and injected by a dependent user.

Implants and slow-release injections which wear off over a much longer timeframe have also been investigated.

A particular problem occurs when the need for pain relief is long-term - when the evidence for the benefit of opioids is less clear.

In the US, one cause of the opioid epidemic is over-prescribing, particularly among those with long-term pain.

For people with acute pain, opioids can be used alongside other drugs - including commonplace painkillers like paracetamol, ibuprofen and aspirin.

When treating patients who are dying, meticulous assessments of the causes of pain are needed to understand the best way to improve it, while minimising potential side-effects.

For example, cancer patients with pain as a result of nerve damage caused by chemotherapy might first be treated with paracetamol and a tricyclic antidepressant.

If that doesn't help, or the patient is in more severe pain, opioids may be introduced - again, this is often in combination with other drugs.

For people who are dying, opioids are very often the most effective way to relieve pain. Anywhere between 30% and 94% of people with advanced cancer are thought to experience pain and about half of cancer patients were prescribed an opioid in the last three months of their life.

If used appropriately, and used in amounts appropriate to patients' symptoms, opioids are not only safe, they are essential for good symptom control.

The events in Gosport and the addiction crisis in the United States have put the medical profession's use of opioids under intense scrutiny.

Better education and training might be one way to make sure they are used appropriately for those who might benefit, so that potential harms are avoided.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Katherine Sleeman is a National Institute for Health Research clinician scientist and honorary consultant in palliative medicine at the Cicely Saunders Institute, King's College London.

Prof Sir John Strang is director of the National Addiction Centre at King's College London's Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience. He has worked on ways to improve adherence to treatments and to reduce abuse of opioids, including joint work with the pharmaceutical industry, as well as the development of antidotes for overdoses. More details of his work can be found here.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie