Schools in Beirut suburb fear return to war after new Israeli strikes

BBC

BBCIt was a typical Friday lunchtime in Beirut's southern suburb. Then, a single warning, posted in Arabic on X by a spokesperson for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), triggered panic and chaos in the densely populated area known as Dahieh.

"Urgent warning to those in the southern suburb of Beirut," it read. The post included a map of a residential area, marking a building in red and two nearby schools. The IDF identified the building as a Hezbollah facility, and ordered the immediate evacuation of the schools.

An air strike was imminent.

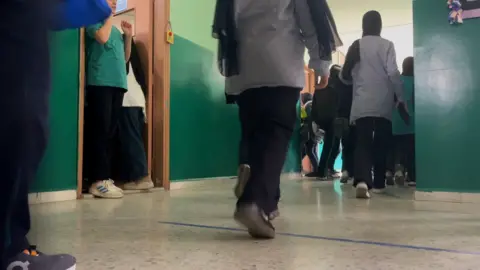

What followed were scenes of sheer panic. Parents rushed towards the threatened area to collect their children from the schools, while residents fled in the opposite direction, visibly shaken and fearful.

"It was total chaos," recalls Ahmad Alama, the director of St Georges School, one of those highlighted on the map. "We tried to contain the situation as much as we could, but it was crazy."

The area was soon cleared, and Israeli forces destroyed the marked building, which they said was a warehouse storing Hezbollah drones.

The strike, carried out two weeks ago, was the first on Dahieh – an area with a strong Hezbollah presence – since a ceasefire ending the war between Israel and Hezbollah took effect last November.

It came hours after two rockets were launched from southern Lebanon towards northern Israel. Israel said it intercepted one rocket, while the other fell short of the border.

Hezbollah, the Iran-backed militant and political group, denied involvement. Israel described the rocket fire as a ceasefire "violation", while the office of Lebanon's president, Joseph Aoun, condemned the Israeli strike as a "violation of the agreement".

"We thought the war had ended with the ceasefire," says Mr Alama, "But unfortunately, we're still living it every day."

- What is Hezbollah and why has it been fighting Israel in Lebanon?

- Hezbollah at crossroads after blows from war weaken group

Despite the ceasefire, Israel has continued near-daily strikes on people and targets it says are linked to Hezbollah, saying it is acting to stop Hezbollah from rearming. The strikes have mainly occurred in southern Lebanon, but the recent bombings in Dahieh have sparked particular alarm.

On 1 April, a second Israeli strike hit the area – this time without warning – killing a Hezbollah commander and three other people, according to the Lebanese health ministry.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEvacuation drills

Mr Alama has been running St Georges School for 30 years. It serves around 1,000 children of all ages, boys and girls. Although religion is part of the curriculum for older pupils, he describes the school as secular.

It is also well-known in the community for its association with the Lebanese pop star and talent show judge, Ragheb Alama – Ahmad Alama's brother and the school's owner.

The recently destroyed building lies just metres from the school. It isn't the only nearby scene of devastation. Another building, opposite one of St Georges' gates, remains a massive pile of rubble – brought down by Israeli air strikes before the ceasefire.

During the war, the schools were closed. They didn't have to deal with situations such as the one they faced. Now reopened, they are braced for the possibility of more bombing.

The school has devised evacuation plans, designating emergency meeting points in the basement and routes for pupils and staff to follow in case of any danger.

There are also new communication plans with parents to prevent a repeat of the chaos of last month's strike. Children are now routinely reminded of these procedures, with regular evacuation drills.

Students, staff, and parents alike are traumatised by what happened, Mr Alama says.

Initially, the school considered cutting back on extracurricular activities to make up for lost learning, but they changed their minds.

"We decided otherwise," Mr Alama says. "Pupils shouldn't pay the price for something they aren't responsible for. We've actually ended up increasing these activities – these kids need to release some of the pressure on them."

Reminders everywhere

Nearly five months into the ceasefire, the return of Israeli air strikes to Beirut has intensified fears of a return to all-out war.

The ceasefire was meant to end more than 13 months of conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, which began when Hezbollah launched attacks on Israeli military positions the day after the Hamas attacks on southern Israel on 7 October 2023, saying it was acting in solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza.

The conflict escalated in September 2024, when Israel launched a devastating air campaign across Lebanon and invaded the south of the country.

Dahieh, deserted during the war, is bustling again. Shops have reopened, hookah smokers are back at crowded cafes, and the suburb seems as busy as before, with its persistently paralysing traffic.

But amid these signs of normality, scenes of destruction serve as a reminder of the pounding this area endured just months ago.

Some 346 buildings in the area were destroyed and another were 145 partly damaged by Israeli air strikes, according to a municipal official. Israel said it targeted Hezbollah facilities and weapons caches.

In many neighbourhoods, the rubble is still being cleared. The roar of bulldozers and jackhammers drilling into piles of debris is almost constant.

Some of the mounds of debris have Hezbollah flags planted on top of them, while large and small portraits of Hassan Nasrallah, the former Hezbollah leader killed by Israel during the war, line the roads.

However, amid the customary signs of defiance, many are now expressing a deep concern not always voiced – at least in front of cameras – by residents of Dahieh.

"The destruction is terrifying. I see the destroyed buildings and I cry," says Sawsan Hariri, the headteacher of Burj High School, also in Dahieh.

The school, which also sits opposite a flattened building, sustained damage from nearby strikes.

"It's depressing. Walking on the street, driving your car - it's all just depressing."

Ms Hariri used to live on the top floor of the school building with her husband and daughter, but their home has been destroyed. They now rent a flat nearby.

Before the war, Burj High School had around 600 pupils. Now, it has barely 100.

Many parents are reluctant to send their children back amid the scenes of destruction and the constant buzz of machinery. Others were concerned about the health risks, with thick dust still filling the air.

After the ceasefire, owners of the private school made some basic repairs at their own expense.

Hezbollah, which is banned as a terrorist organisation in many countries but in Lebanon is a political and social movement as well as a paramilitary force, has given those who lost their homes $12,000 for a year's rent and has offered to cover the costs of repairs to apartments. However, schools and other institutions have not received any aid.

The Lebanese government has pledged to set up a reconstruction fund, which the World Bank estimates will cost $11bn nationwide. But international donors are believed to be insisting on the disarmament of Hezbollah and political reform – conditions that appear a distant prospect.

Though the clearing of rubble is expected to be over by the end of the year, few expect large-scale rebuilding to follow anytime soon.