Titanic scan reveals ground-breaking details of ship's final hours

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

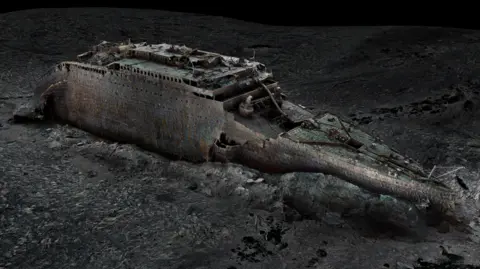

Atlantic Productions/MagellanA detailed analysis of a full-sized digital scan of the Titanic has revealed new insight into the doomed liner's final hours.

The exact 3D replica shows the violence of how the ship ripped in two as it sank after hitting an iceberg in 1912 - 1,500 people lost their lives in the disaster.

The scan provides a new view of a boiler room, confirming eye-witness accounts that engineers worked right to the end to keep the ship's lights on.

And a computer simulation also suggests that punctures in the hull the size of A4 pieces of paper led to the ship's demise.

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

Atlantic Productions/Magellan"Titanic is the last surviving eyewitness to the disaster, and she still has stories to tell," said Parks Stephenson, a Titanic analyst.

The scan has been studied for a new documentary by National Geographic and Atlantic Productions called Titanic: The Digital Resurrection.

The wreck, which lies 3,800m down in the icy waters of the Atlantic, was mapped using underwater robots.

More than 700,000 images, taken from every angle, were used to create the "digital twin", which was revealed exclusively to the world by BBC News in 2023.

Because the wreck is so large and lies in the gloom of the deep, exploring it with submersibles only shows tantalising snapshots. The scan, however, provides the first full view of the Titanic.

The immense bow lies upright on the seafloor, almost as if the ship were continuing its voyage.

But sitting 600m away, the stern is a heap of mangled metal. The damage was caused as it slammed into the sea floor after the ship broke in half.

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

Atlantic Productions/MagellanThe new mapping technology is providing a different way to study the ship.

"It's like a crime scene: you need to see what the evidence is, in the context of where it is," said Parks Stephenson.

"And having a comprehensive view of the entirety of the wreck site is key to understanding what happened here."

The scan shows new close-up details, including a porthole that was most likely smashed by the iceberg. It tallies with the eye-witness reports of survivors that ice came into some people's cabins during the collision.

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

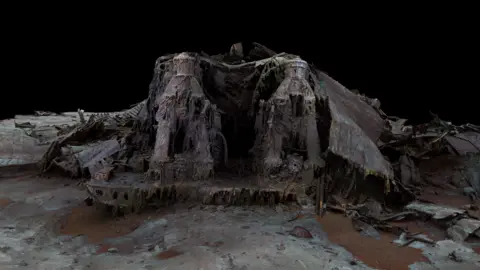

Atlantic Productions/MagellanExperts have been studying one of the Titanic's huge boiler rooms - it's easy to see on the scan because it sits at the rear of the bow section at the point where the ship broke in two.

Passengers said that the lights were still on as the ship plunged beneath the waves.

The digital replica shows that some of the boilers are concave, which suggests they were still operating as they were plunged into the water.

Lying on the deck of the stern, a valve has also been discovered in an open position, indicating that steam was still flowing into the electricity generating system.

This would have been thanks to a team of engineers led by Joseph Bell who stayed behind to shovel coal into the furnaces to keep the lights on.

All died in the disaster but their heroic actions saved many lives, said Parks Stephenson.

"They kept the lights and the power working to the end, to give the crew time to launch the lifeboats safely with some light instead of in absolute darkness," he told the BBC.

"They held the chaos at bay as long as possible, and all of that was kind of symbolised by this open steam valve just sitting there on the stern."

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

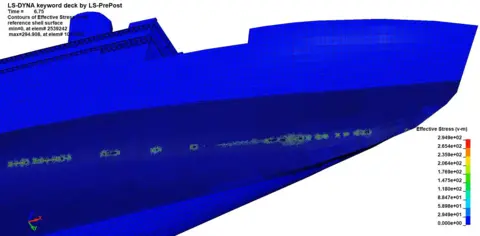

Atlantic Productions/MagellanA new simulation has also provided further insights into the sinking.

It takes a detailed structural model of the ship, created from Titanic's blueprints, and also information about its speed, direction and position, to predict the damage that was caused as it hit the iceberg.

"We used advanced numerical algorithms, computational modelling and supercomputing capabilities to reconstruct the Titanic sinking," said Prof Jeom-Kee Paik, from University College London, who led the research.

The simulation shows that as the ship made only a glancing blow against the iceberg it was left with a series of punctures running in a line along a narrow section of the hull.

Jeom Kee-Paik/ University College London

Jeom Kee-Paik/ University College LondonTitanic was supposed to be unsinkable, designed to stay afloat even if four of its watertight compartments flooded.

But the simulation calculates the iceberg's damage was spread across six compartments.

"The difference between Titanic sinking and not sinking are down to the fine margins of holes about the size of a piece of paper," said Simon Benson, an associate lecturer in naval architecture at the University of Newcastle.

"But the problem is that those small holes are across a long length of the ship, so the flood water comes in slowly but surely into all of those holes, and then eventually the compartments are flooded over the top and the Titanic sinks."

Unfortunately the damage cannot be seen on the scan as the lower section of the bow is hidden beneath the sediment.

Atlantic Productions/Magellan

Atlantic Productions/MagellanThe human tragedy of the Titanic is still very much visible.

Personal possessions from the ship's passengers are scattered across the sea floor.

The scan is providing new clues about that cold night in 1912, but it will take experts years to fully scrutinise every detail of the 3D replica.

"She's only giving her stories to us a little bit at a time," said Parks Stephenson.

"Every time, she leaves us wanting for more."