Scientists discover protection from PFAS chemicals

MRC Toxicology Unit

MRC Toxicology UnitScientists believe they have found a way to protect people from a toxic and long-lasting "forever chemical".

Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) are man-made chemicals which can be found in items such as waterproof clothing, non-stick pans, lipsticks or food packaging.

They are used for their grease and water repellence, but do not degrade quickly in nature and have been linked to health issues such as higher risks of certain cancers.

A University of Cambridge study found a certain species of microbe found in the human gut could absorb various PFAS molecules and lessen its harmful effects.

'Slow poison'

Peter Northrop/MRC Toxicology Unit

Peter Northrop/MRC Toxicology UnitThere has been increasing concern about the environmental and health impacts of PFAS, which take thousands of years to break down in the environment.

Most people are exposed to the substances through water and food.

In some cases, the chemical is cleared out of the body through urine, but it could also stay in the body for years.

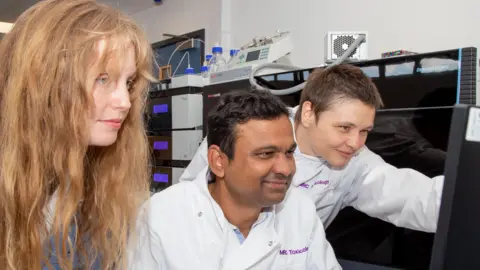

PFAS are so widespread that they are in all of us, said Dr Anna Lindell, a researcher at the University of Cambridge's MRC Toxicology Unit and first author of the study.

"PFAS were once considered safe, but it's now clear that they're not.

"It's taken a long time for PFAS to become noticed because at low levels they're not acutely toxic. But they're like a slow poison."

Researcher and co-author, Dr Indra Roux, added as PFAS were already in the environment and in our bodies, we needed to mitigate their impact.

"We haven't found a way to destroy PFAS, but our findings open the possibility of developing ways to get them out of our bodies where they do the most harm."

MRC Toxicology Unit

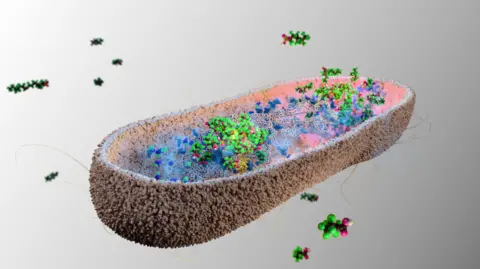

MRC Toxicology UnitResearchers found certain species of human gut bacteria had a remarkably high capacity to soak up PFAS and store it in clumps inside their cells.

Dr Kiran Patil, the senior author of the report, said: "Due to aggregation of PFAS in these clumps, the bacteria themselves seem protected from the toxic effects."

The scientists made their findings after nine of the bacterial species were introduced into the guts of mice to "humanise" the mouse microbiome.

The bacteria rapidly accumulated PFAS eaten by the mice - which were then excreted in faeces.

It was the first evidence that the gut microbiome could be helpful in removing toxic PFAS chemicals from our body.

It has not yet been directly tested in humans.

The researchers planned to create probiotic dietary supplements to boost the levels of the helpful microbes in our gut, to protect against the toxic effects of PFAS.

Dr Lindell and Dr Patil co-founded a startup, Cambiotics, with entrepreneur Peter Holme Jensen to develop a probiotic dietary supplement to boost the levels of the helpful microbes and protect against the toxic effects of PFAS.

MRC Toxicology Unit

MRC Toxicology UnitFollow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.