Great Bibles reunited for first time in 500 years

BBC

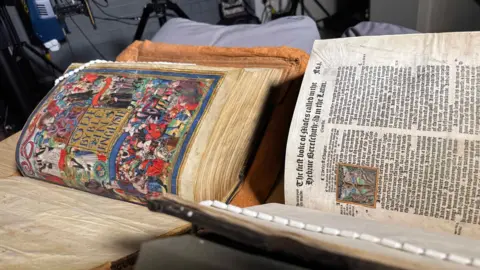

BBCUnique copies of the Great Bibles of Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell have been reunited for the first time in nearly 500 years.

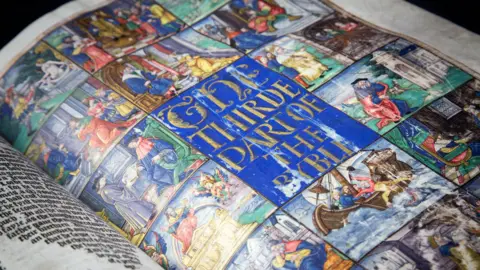

The copies, made in 1538-9, were printed on parchment and carefully hand-coloured by Europe's finest artists and was the first authorised edition in English.

Thomas Cromwell was a strong supporter of religious reform and these Bibles were commissioned by him as part of the campaign to convince the King.

They have gone on display as part of the Treasures exhibition in the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, in what has been called "a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity".

Hidden in Plain Sight is a project that employs a range of technologies, from 3D microscopy to DNA analysis, which show for the first time how ancient books were used and modified.

Research has revealed different layers to illustrations with deliberate modifications that were changed due to the political developments of the time.

The project has revealed Cromwell had his portrait painted and pasted into the title page of the St John's copy – a move expertly hidden for centuries.

The opening title page was further manipulated to gain Henry's support by altering an image of a courtly woman to resemble Jane Seymour, Henry's beloved and recently deceased, consort.

National Library of Wales

National Library of WalesResearchers on the project said these discoveries raises more questions about how the Bibles were made, with Dr Harry Spillane adding that technology was revealing more about the books to this day.

He said: "Although these books have been around for 500 years, it's only with new technologies that we have been able to see all of the changes that have been made underneath.

"We can see that bits of paper have been pasted on, or often multiple layers glued on as a more perfect design is completed.

"And seeing them side by side helps people understand how, even 500 years ago, changes are being made to images in ways that build on discussions we are having today about deep fakes and AI. People's faces are changing, images are moving around."

Although the text is almost identical in both bibles, the illustrations vary much more.

Dr Suzanne Paul from Cambridge University Library said the technology being used enabled specialists to learn more about "the archaeology of the bibles".

"We know particular workshops that were doing work for the royals and by analysing the different pigments in the book to other paintings and books from this time we can potentially find out where the bibles were made," she added.

"The artists might not have left their physical signature, but they might have left their chemical signature in the book for us to find."

Henry VIII ordered copies of the Great Bible to be distributed to every parish in England and Wales, which was the catalyst for translating the Bible into Welsh in 1588, known as the William Morgan's Bible.

Maredudd ap Huw, curator of manuscripts at library, said the exhibition was "a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity".

He added: "These two Bibles are not going to be brought together again for a long time.

"There is a golden opportunity on a historical level to see two milestones in the history of England and Wales during the Tudor period. Without the English Bible, the Welsh language would not be spoken today."

The exhibition is open until 22 November.