Russia gripped by human rights crackdown, says UN

Reuters

ReutersHuman rights in Russia have “severely deteriorated” since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, culminating in a “systematic crackdown” on civil society, a UN report has found.

The investigation details police brutality, widespread repression of independent media and persistent attempts to silence Kremlin critics using punitive new laws.

Mariana Katzarova, the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Russia, was denied entry into the country and compiled the report by speaking to political groups, activists and lawyers.

She found “credible reports” of torture and allegations of sexual violence, rape and threats of sexual abuse by police.

The Kremlin has not commented publicly since its release.

Human rights abuses in Russia have been well documented during the Vladimir Putin era, but the latest UN report pays particular attention to how the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine has accelerated what it says was previously a “steady decline”.

It details how laws passed in recent years targeting the spread of so-called fake news, and individuals or organisations deemed to have received foreign support, have sought to “muzzle” any opposition, both physically and online.

The new laws have led to “mass arbitrary arrests” and long prison sentences, it adds.

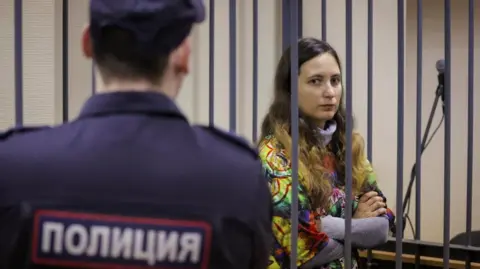

Reuters

ReutersAmong the cases the report highlights is that of Artyom Kamardin, who was jailed for seven years for reading an anti-war poem in public - an act authorities deemed to be “inciting hatred”.

Ms Katzarova told the BBC: “Russians are getting shockingly long prison sentences.

"It’s seven years for reading an anti war-poem, or saying a prayer by a priest which was against the war, or producing a play perceived to be anti-war. Two women are still in prison for that in Russia.”

She praised those who continue to organise despite threats and said she believes opposition to the war is quietly widespread.

“As in any totalitarian, authoritarian state, people don't want to get in trouble - it doesn't mean that they are supportive of some madness, an aggressive war against their neighbour,” she added.

The report accuses the government of seeking to propagate its views on the Ukraine conflict among children via the introduction of mandatory school lessons, officially labelled as “important conversations”.

“Children refusing to attend such classes and their parents are subject to pressure and harassment,” it adds. The report highlights the case of a fifth-grader from Moscow who was interrogated by police after skipping the class, before their mother was charged with “failing to fulfil parental duties”.

It found that many men sent to Ukraine “have been mobilised by deception, the use of force, or by taking advantage of their vulnerability”, while those who have refused to fight have been held in detention centres in occupied areas and “threatened with execution, violence or a prison sentence if they did not return to the front lines”.

Men from indigenous communities make up a disproportionate number of those drafted into the army, it found, and there is evidence “authorities have imposed travel restrictions, blocking exit routes from towns and villages during mobilisation sweeps”.

Ms Katzarova said: “Indigenous people… are really facing extinction if this continues.

"I think, partly my guess and the trends that indigenous leaders are painting, is that this is part of the Russian authorities really wanting to send to the front line ‘disposable people’, not the Slavs from St Petersburg or Moscow.”

Elsewhere in the report:

- It accuses judges of acting as a “mouthpiece” for the government because of the depth of political interference

- It describes Russia as an “increasingly homophobic society”, pointing to recent laws curtailing the freedoms of LGBT+ people

- It says female anti-war activists have been disproportionately affected by the crackdown on dissent and are “even more vulnerable in custody”

- It describes a “climate of fear and repression” amid widespread police brutality in Chechnya, adding that the southern republic should serve as a “warning” for what could happen elsewhere in Russia

The report deals with human rights in Russia’s internationally recognised borders, so does not comment on reported abuses in Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova.