Atacms: What we know about missile system Ukraine has used to strike Russia

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor the first time, Ukraine has fired US-supplied longer-range missiles at a target inside Russian territory.

Until now, Washington had refused to allow strikes on Russian territory with Atacms missiles because it feared they would escalate the war - but in the past few days, the US has changed its stance.

Here's what we know about the Atacms missile system.

Why has the US allowed Ukraine to use long-range missiles inside Russia?

Ukraine has been using Atacms on Russian targets in occupied Ukrainian territory for more than a year.

American munitions and hardware are already being used inside Russia's Kursk border region.

But the US had never allowed Kyiv to use the Atacms inside Russia – until now.

Ukraine had argued that not being allowed to use such weapons inside Russia was like being asked to fight with one hand tied behind its back.

The change in policy reportedly comes in response to the recent arrival of North Korean troops to support Russia in the Kursk region, where Ukraine has occupied territory since August.

Also, Donald Trump’s imminent return to the White House is raising fears over the future of US support for Ukraine, and President Biden is apparently keen to do all he can to help in the little time he has left in office.

Strengthening Ukraine's hand militarily – so the thinking goes - could grant Ukraine leverage in any peace talks that may lie ahead.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has not yet confirmed the move. But he said on Sunday: "Strikes are not made with words ... The missiles will speak for themselves."

What is Atacms?

Getty Images

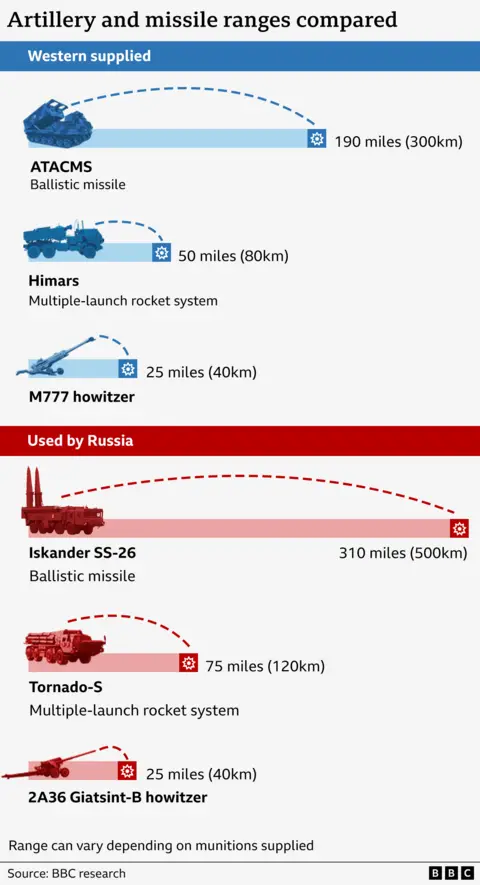

Getty ImagesThe Army Tactical Missile System is a surface-to-surface ballistic missile capable of hitting targets at up to 300km (186 miles). This longer range makes them particularly important for Ukraine.

Built by the defence manufacturer Lockheed Martin, the missiles are fired from either the tracked M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) or the wheeled M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (Himars). Each one costs around $1.5m (£1.2m).

Atacms (pronounced “attack-‘ems”) are fuelled by solid rocket propellant and follow a ballistic path into the atmosphere before coming back down at a high speed and high angle, making them difficult to intercept.

They can be configured to carry two different types of warhead. The first is a cluster fitted with hundreds of bomblets designed to destroy lighter-armoured units over a wide area. These might include parked aircraft, air defences and concentrations of troops. Cluster warheads, while useful, risk leaving behind unexploded bomblets which pose a risk long after the fighting has stopped.

The second type is a single warhead, a 225kg high explosive variant of which is designed to destroy hardened facilities and larger structures.

Atacms have been around for decades. They were first used in the Gulf War of 1991.

The US Army is replacing it with the next-generation Precision Strike Missile, a faster, slimmer weapon that can go out to 500km. There is no suggestion Ukraine will be getting these.

What effect will the missiles have on the battlefield?

Ukraine first used the missiles in a strike on Russia's Bryansk region on Tuesday, according to the ministry of defence in Moscow, just a day after receiving clearance from US officials.

Five missiles were shot down and one damaged, with its fragments causing a fire at a military facility in the region, it said.

Tuesday's strike represented the first time the long-range missiles have been used on Russia's internationally-recognised territory after Washington signalled Ukraine had permission to do so. Russia has vowed to "react accordingly.”

Initially it was thought Ukraine would strike targets inside Russia's Kursk region, where Ukrainian forces hold over 1,000 sq km of territory.

Ukrainian and US officials expect a counter-offensive by Russian and North Korean troops to regain territory in Kursk.

Ukraine may use Atacms to defend against the assault, targeting Russian positions including military bases, infrastructure and ammunition storage.

The supply of the missiles will probably not be enough to turn the tide of the war. Russian military equipment, such as jets, has already been moved to airfields further inside Russia in anticipation of such a decision. However, moving equipment further back from the front lines may make life difficult for Russian troops as supply lines are stretched and air support takes longer to arrive.

And the weapons may grant Ukraine some advantage at a time when Russian troops have been gaining ground in the country's east and morale is low.

"I don't think it will be decisive," a Western diplomat in Kyiv told the BBC, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

"However, it’s an overdue symbolic decision to raise the stakes and demonstrate military support to Ukraine.

"It can raise the war cost for Russia."

There are also questions over how much ammunition will be provided, said Evelyn Farkas, who served as deputy assistant secretary of defence in the Obama administration.

"The question is, of course, how many missiles do they have? We have heard that the Pentagon has warned there aren’t that many of these missiles that they can make available to Ukraine."

Farkas added that the Atacms could have a "positive psychological impact" in Ukraine if they are used to strike targets such as the Kerch Bridge, which links Crimea to mainland Russia.

The US authorisation had a further knock-on effect: with Ukraine using Storm Shadow missiles inside Russia. Storm Shadow is a Franco-British long-range cruise missile with similar capabilities to the American Atacms.

That authorisation appeared to have been granted in the days following the US announcement. On 20 November, Ukraine fired Storm Shadow missiles into Russia for the first time.

Could it lead to escalation of the war?

The Biden administration had for months refused to authorise Ukraine to hit Russia with long-range missiles, fearing escalation of the conflict.

Vladimir Putin has warned against allowing Western weapons to be used to hit Russia, saying Moscow would view that as the “direct participation” of Nato countries in the war in Ukraine.

“It would substantially change the very essence, the nature of the conflict,” Putin said in September. “This will mean that Nato countries, the USA and European states, are fighting with Russia.”

Russia has set out “red lines” before. Some, including providing modern battle tanks and fighter jets to Ukraine, have since been crossed without triggering a direct war between Russia and Nato.

Kurt Volker, a former US ambassador to Nato, said: “By restricting the range of Ukraine’s use of American weapons, the US was unjustifiably imposing unilateral restrictions on Ukraine’s self-defence."

He added that the decision to limit the use of Atacms was "completely arbitrary and done out of fear of ‘provoking’ Russia."

“However, it is a mistake to make such a change public, as it gives Russia advance notice of potential Ukrainian strikes.”

How will Donald Trump react?

Shutterstock

ShutterstockThe move comes just two months before Donald Trump returns to the White House.

He has already said he intends to bring the war in Ukraine to a swift end – without specifying how he plans to do it – and he could cancel the use of the missiles once he takes office.

President-elect Trump has not yet said whether he would continue the policy, but some of his closest allies have already criticised it.

Donald Trump Jr, Trump's son, wrote on social media: "The military industrial complex seems to want to make sure they get World War Three going before my father has a chance to create peace and save lives."

Many of Trump's top officials, such as Vice President-elect JD Vance, say the US should not provide any more military aid to Ukraine.

But others in the next Trump administration hold a different view. National Security Adviser Michael Waltz has argued that the US could accelerate weapons deliveries to Ukraine to force Russia to negotiate.

Which way the president-elect will go is unclear. But many in Ukraine fear that he will cut off weapons deliveries, including Atacms.

"We are worried. We hope that [Trump] will not reverse [the decision]," Oleksiy Goncharenko, a Ukrainian MP, told the BBC.

Additional reporting by Tom McArthur