'We lost our brothers to violence - why siblings need support'

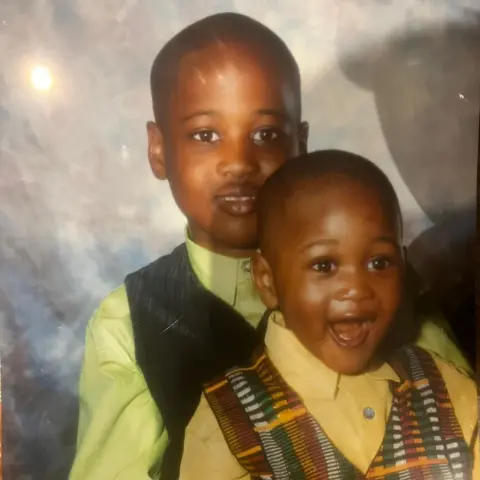

Family photo

Family photo Otis Lawson was just 13 years old when police came to his home and told his mother that his big brother Godwin had been stabbed.

"That scream, I will never forget that," he says. "Something just went through me, and I don't know how, but I knew my brother had passed away. "

Godwin, a promising footballer with a place at the Oxford United Academy, was 17 years old when he was killed in east London.

"He was like my hero, honestly," Otis says. "Having a big brother to speak to. He was good at football obviously, really talented, quite popular. I always looked up to my older brother."

Family photo

Family photoBut suddenly Godwin had been violently taken from him and in that moment, Otis says, everything changed.

"That scarred me quite a bit, because I always walked with.. if that could happen to my older brother, then..." he says.

"Till I was about 16 , 17, I always thought my life could be taken from me.

"I had a lot of people telling me things would be OK, things would be alright, but they weren't really in the shoes that I was in."

He explains that when he looked around at other young people who had lost loved ones to violence, their stories never ended happily: it seemed either they became victims themselves, or got involved in crime.

No-one seemed to have a positive story. So why, he reasoned, should his be any different?

'People take matters into their own hands'

"After losing Godwin, it would have been easy for me to go down the route other people take," says Otis.

"I have definitely seen people take matters into their own hands, and resort to them being violent, or them perceiving life in a certain way; like, life is worthless.

"They might feel like they need to carry a knife in order to survive. "

He credits the loving support of his family, and his enthusiasm for sport, for helping him make positive choices and cope with his grief.

His mother, Yvonne Lawson, set up the Godwin Lawson Foundation, to support young people through sport and education, and Otis has been developing his own project, called Elite Squad.

We meet him at one of his training sessions at the Lee Valley Athletics Centre in Enfield, north London, over the summer holidays, where he is coaching a small group of enthusiastic teenage boys.

"I hope it helps them navigate through life, helps them be disciplined, work hard and achieve," he explains.

"I offer mentoring, I just try to guide them really."

But he believes there needs to be far more help aimed specifically at young people who have lost a sibling, from someone with lived experience.

"Someone who has been in their position, who is able to speak to them, put an arm around them, and guide them through."

Family photo

Family photo On the other side of London, in Croydon, Tilisha Goupall is also determined to make a difference.

I first met Tilisha in August 2017, just days after her little brother Jermaine had been murdered in Thornton Heath, south London.

She was 24 years old then, and although in shock, she wanted to appeal for information to find his killers and to stress that her brother had been an innocent 15 year old, attacked on his way home.

There is now a memorial plaque at the spot where he died.

"We were best friends, honestly," she says.

"We never had an argument a day in our lives."

Because of their age gap, and both being brought up by their dad, she says she often took on a caring responsibility, and when Jermaine had not come home as expected that evening, she had been calling him to find out where he was.

Jermaine did not answer the phone. Instead, the police knocked on her door to tell her he had been stabbed.

Tilisha rushed to the scene, but despite the efforts of paramedics, she was told there was nothing more they could do.

"I had to literally break that news to my dad, with people in the crowd just watching," she remembers.

"You're almost thinking... this is a surreal moment, you don't think it's real, you think you're dreaming. I just shut down and started crying."

'They've lost their sense of purpose'

In the weeks and months that followed, she realised that even well-meaning people seemed to not really understand what she was going through.

"It was always, oh, 'how's your parents, how's your parents?', not realising that I lived with the trauma, I've been there. You're kind of sidelined a little bit more."

Seven years on, Tilisha has become a well known campaigner against knife crime, creating the Justice for Jermaine Foundation, giving talks in schools and teaching teenagers how to use bleed kits to give emergency treatment if a friend is attacked.

She has also been offering support to young people who lose a sibling, reaching out to bereaved families in Croydon and trying to offer the help she wishes she had received herself.

"I show them they've got support and a voice, and they are noticed," she says.

But she is clearly frustrated that there is not more structured and recognised support available.

"It's sad, it's heartbreaking, because I sit there and I cry for them. You almost forget about your pain and focus on their support, because you know that if you don't do nothing, nothing will be done."

Like Otis, she too has known young people lose a brother or sister and make the wrong choices.

"The thought process is, alright, I'm going to carry a knife now. You killed my sibling, I'm either going to find you, or I'm going to carry a knife to protect myself, and whatever happens happens.

"Because they've lost their sense of purpose, and almost the fear... They become fearless, actually."

She is hoping to secure funding for a new siblings support project to be launched next year, where young people can feel safe to talk to others who've been through the same type of bereavement.

"We need to lean on each other. It's about the community. It's about that village," she says.

"If we're not supporting our village then we're never going to make an impact at all."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]