RAAC concrete house was meant to be our forever home

BBC

BBCHome owners have told the BBC they are living in fear of crippling bills after finding out a cheap version of concrete that could be at risk of collapse was used in their houses.

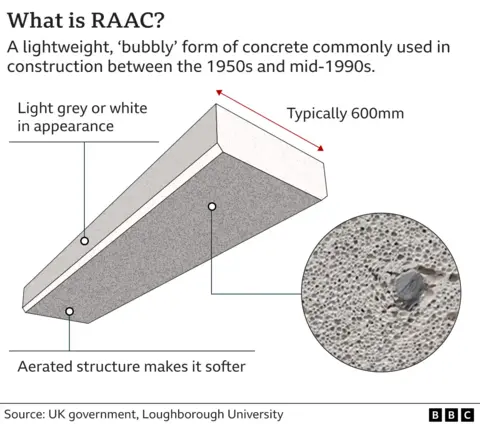

Reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) was used mostly in flat roofing, but also in floors and walls, between the 1950s and 1990s.

It has been found in public buildings across the country sparking fears about the potential collapse of ceilings and walls - and many local authorities are now moving to inspect council houses.

But whereas current tenants are having their repair costs covered, many people who bought their council houses say they have no-one to turn to.

Ashleigh Mitchell bought her home near Livingston in West Lothian in 2013. She lives there with her partner and small child.

Her street in the Chestnut Grove area of Craigshill has 13 homeowners and seven housing association tenants.

Ashleigh says she was “absolutely shocked” and “panicked” when she was told by the local housing association, Almond Housing, her home was 100% RAAC-made.

Her housing association neighbours are moving out permanently and their houses will be boarded up with metal bars to stop people entering.

Ashleigh says she has been given estimates in the region of £40,000 for the whole house to be appropriately treated.

“I’m devastated because this was meant to be our forever home," she says.

“We’re in complete limbo. People are scared, people are terrified. They’re saying it's dangerous, it could crumble, it could fall on us.

“The Scottish government need to step in and help homeowners.”

Another Craigshill resident, Karen Chappell, has been going to meetings with those residents like Ashleigh who are trying to press for more support.

The housing association has advised Karen to get a survey done – but she says this could cost in the region of £2,000.

“That's a lot on top of the usual outgoings of a family," Karen says.

“I don’t feel particular well supported by the establishments around us that are supposed to be there to do so, there’s no information.

“We are scared, I’m scared about my house which I’ve poured all my savings into. It means a lot to me.

"I bring my children up there and I think, 'is it going to be worth anything? Is it going to disintegrate? Is it safe?'”

Almond Housing has been approached for comment.

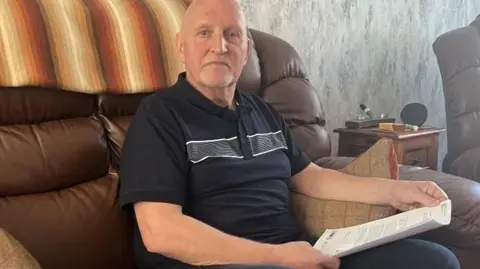

In nearby Bathgate, Jim Allan says the house he has lived in since 1968 is now "worthless".

His father bought the family's council home in 2003 and Jim took it on 12 years ago when his dad died.

But he says his happy memories of living in the house are being overshadowed after West Lothian Council informed him that the neighbouring council houses had traces of RAAC.

Council tenants are to be moved out of their homes while remedial work is completed but Jim says he got a letter saying "you’re on your own".

He has been given estimates putting the work required in the region of £50,000.

However, he was also advised he would be better “putting a match” to the property given the scale and cost of the issue.

“I can’t sleep at night because it’s so stressful," Jim says.

"I don’t have that kind of money. I don’t know what to do.”

He says his hopes of selling the property have been dashed.

"I have no equity going forward to move on with my life in the future," he says.

Jim says his father would never have bought the property if they had known it was defective.

West Lothian Council said that suggestions it sold homes while aware of RAAC safety issues were “inaccurate”.

The authority said it was currently following guidance issued by the Institute of Structural Engineers in April 2023 regarding the presence of RAAC.

A statement said: “The council last sold former council homes in 2017/18 when the Right to Buy scheme ended and this pre-dates the identification of RAAC planks in a limited number of council houses.

“The council has no statutory obligations in relation to privately owned properties, and therefore, has no power to support homeowners other than in limited circumstances.”

Some people have been in this position for a long time.

Kerry Macintosh's home in the Deans South area of Livingston was condemned in 2004 due to RAAC.

She embarked on a two-decade-long campaign for support which will soon see her move into a ‘like-for-like’ new property on the estate.

The old properties have been demolished.

She wants to see others such as Jim, Ashleigh and Karen get the same support.

Kerry wants financial support for all homeowners and a public inquiry on why the former council properties were sold with structural defects.

She also wants the UK chancellor to review his budget to include support for RAAC home owners.

“Home owners have been treated absolutely appallingly," Kerry says.

“This is the UK RAAC scandal and this will get bigger and we will not be quiet until our voices are heard, until all homeowners get financial support.”

Building safety and local government finance are the responsibility of the Scottish government.

However, Housing Minister Paul McLennan told the BBC he wanted the UK government to step in with support.

He said that without this it was “hard to say” what his government could offer.

A UK government spokesperson said the issue was the responsibility of the Scottish government, which was getting a record financial settlement.

The SNP MP for Livingston, Hannah Bardell, said that, given its historical nature, the UK government should provide a legacy fund for homeowners.

“These houses were built before devolution, before the Scottish Parliament existed," she said.

“The extent of the problem is a lot bigger than we currently understand."

Peter Drummond, the chair of practice for the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, said RAAC was commonly understood in the UK to have a design life of no more than 30 years and concerns about defects first arose in the 1980s.

“In Scotland, RAAC is primarily found in educational and healthcare properties," he said.

"It is, however, becoming increasingly clear that housing – both publicly and privately owned – has been affected.

“The owners of these private houses find themselves facing very significant repair bills and are likely to find themselves unable to secure lending against the property because of the defect.

"They are therefore in an iniquitous position through no fault of their own.”