The US island ruled by alien snakes and spiders

Alamy

AlamyGuam has 40 times more spiders than neighbouring islands – and a population of invasive snakes so voracious, they have emptied the forests of every bird.

Five years ago, Haldre Rogers attended a get-together on the island of Guam – an emerald-green smudge in the western Pacific Ocean, around 2,492km (1,548 miles) from the Philippines. But soon the party was interrupted by an uninvited guest.

It was late evening, and outside there was a hog roasting – the remains of dinner. The fire was going down, though still warm. Everyone briefly walked off to chat. When they came back, there was a brown form curled around the pig – something shiny and scaly, with vertical slit-eyes and a wide, smiling mouth. The creature was ripping off chunks of the pig's flesh and swallowing them whole – slowly gulping them into its pale, distended body.

"It wasn't [exactly] a 400-pound (181kg) pig, but it was a pig for a big party," says Rogers, an associate professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation at Virginia Tech in the US, who has been studying Guam's ecology for the last 22 years.

Alamy

AlamyThe visitor without table manners was a brown tree snake – an alien invader which is thought to have been inadvertently introduced to Guam in the 1940s, perhaps after sneaking onto a cargo ship. Before this, an abundance of native birds had enjoyed an idyllic existence in the island's otherworldly limestone forests. But within just four decades of the snake's debut, these voracious predators had begun emptying the jungle of every single one. Out of 12 species, 10 are now extinct on the island, while the remaining two are clinging on in inaccessible caves and urban areas.

Now that the avian community has been virtually wiped out, Guam's population of some two million snakes – no one really knows how many there are – will hoover up whatever they can find, including rats, shrews, lizards, or, on this occasion, human leftovers.

"I mean, they'll eat anything," says Henry Pollock, executive director of the Southern Plains Land Trust, a non-profit in Colorado, who has previously studied the ecology of Guam. "They'll eat each other."

With a plague of ravenous snakes, and forests that are entirely devoid of the friendly whistles, chirps and caws that once dominated their soundscape, Guam has become notorious as one of the planet's most spectacular ecological debacles. But the consequences of the island's snake infestation extend far beyond its eerily silent, bird-less forests. Here, an evolutionary experiment is unfolding. And one notable beneficiary has eight legs, plenty of eyes – and the good luck to find itself on an island where sharp, hungry beaks are little more than a distant memory.

A web of webs

Rogers is not frightened of spiders – and that's just as well.

On most of the Mariana Islands, there are relatively few spiders in the rainy season, with a large spike as the climate dries out. But not on Guam. The island's limestone forests are an arachno-nightmare all year round – a near-continuous tangle of silvery threads that stretches for miles, where every step you take reveals another web and its hairy host.

There are giant, yellow-bellied banana spiders, with their golden webs in the classic spoked style; scuttling huntsman spiders the size of a human hand; tent-web spiders, which drape their vast pavilions of silk across gaps in the trees. Rogers calls the latter kind the "condo" web, because each one is akin to an apartment complex for creatures with eight legs – they contain hundreds of gleaming eyes, belonging to tens of individual spiders.

"You'll have many females at different levels in this massive web, and then many males hanging around and the edges," says Rogers. These communal webs are also a favourite of tiny Argyrodes spiders, who turn up to steal prey from, and occasionally eat, their much larger hosts. "On Guam these [condo webs] go from ground level, all the way up to the canopy – they can be everywhere," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMost of the time, the whole forest looks like it's been draped in wisps of artificial spider's web for Halloween. "It's enough that when you're hiking, it's common for the person in front to pick up a spider stick and knock down the webs as they go," says Rogers, "otherwise you'll be covered in spider webs… I love it, but it is difficult to get through."

Wherever there is a gap in the trees, the entire space will be filled with webs from hundreds of different spiders, all catching the light at different angles. These collective efforts can easily occupy a space the size of a room. "I had a friend once who ran into the middle of one and just twirled in a circle, making a mummy out of himself with this massive bit of web," says Rogers," he did that to freak out the people he was with".

On another occasion, an assistant of Rogers volunteered to help in the field – only to get a couple of metres into the forest and change her mind. "She was like, 'No, I'm out'," says Rogers.

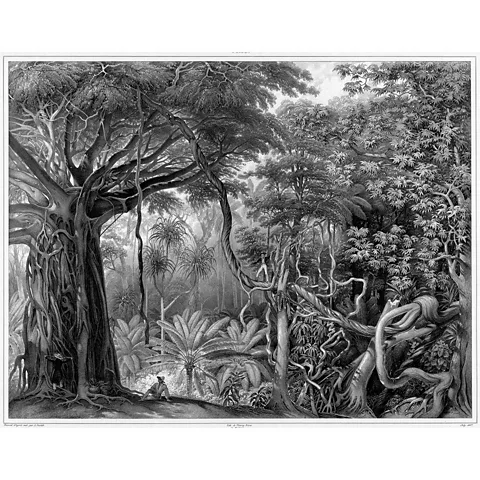

Even without the spiders, which in the native Chamorro language are known as sånye'ye', Guam's limestone forests would be a strange and hostile place, like nowhere else.

Overhead, towering breadfruit trees mingle with the Jurassic shapes of cycads, along with tangantangan (castor-oil) and spiky pandanus trees, forming a low canopy of jungle which is frequently ripped up by typhoons. On the ground, there is very little soil. Instead, plants grow directly out of limestone karst, forcing their roots into tiny fissures in the rock – the forest sits atop an ancient coral reef which has been pushed up over millions of years to form a plateau. Coral heads still litter the forest floor, and where the rock has eroded away, there are sinkholes and caves.

"I think the unique thing is, just like, it's really difficult to walk because – well, imagine walking on sharp rocks," says Rogers. When she takes new field technicians out for surveys, they need time to acclimatise to this rocky ground – she talks about people getting their "karst legs". "It's like getting your sea legs – being able to walk without having to focus on every step," she says.

Alamy

AlamySo, when Rogers decided to take a survey of the number of spiders in 2012, she knew it would be a challenge.

There had always been rumours that Guam was particularly spidery – and that this might have something to do with the absence of birds, which ordinarily love to eat them. However, Rogers explains that the island's population of roughly 180,000 people rarely travel to the other Northern Mariana Islands – while they are all part of a self-governing commonwealth, only Guam is a US territory. As a result, there is little opportunity for comparison. And scientists had never actually checked.

To find out exactly how many arachnids had taken over Guam, Rogers and colleagues set about completing transect surveys in the island's forests. For these, researchers carefully picked their way over the jagged coral reef underfoot while unspooling a roll of tape in a straight line. As they went. they carefully counted the spider's webs in their path which still contained a fanged occupant, if they fell within a metre of the line.

What the scientists found was a population of arachno-spectacular proportions: during the wet season, there were 40 times more spiders in Guam's forests than there were on the nearby islands of Rota, Tinian and Saipan – while in the dry season, when spider populations in the region usually escalate, there were 2.3 times more spiders on Guam. The webs of banana spiders on Guam were also around 50% bigger.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAll year round, Guam's forests were positively glistening with webs: the team found 1.8 and 2.6 webs per metre of transect line in the wet seasons and dry seasons respectively. If extrapolated to Guam's entire forest area this would amount to between 508 and 733 million spiders in total, scampering around on their webs and sucking the juices out of their victims. That's assuming one spider per web, though there are often far more – and only counting those living within two metres of the ground. In terms of spidery body parts, the forest ends up hosting at least 4,064,000,000 eyes and an equal number of hairy, articulated legs.

Rota, Tinian and Saipan are free of brown tree snakes and still have healthy bird populations, so the study suggests that Guam's spider population might once have been unremarkable – before exploding over the last few decades, in the absence of birds. This is partly because of the avian predilection for creatures with eight legs, and also because they compete for the spiders' insect prey – and it fits with research conducted in the Bahamas, which has found that spiders are about 10 times more abundant on islands without lizards.

Since the brown tree snake's arrival, the banana spider's existence on Guam has become so comfortable, they have even stopped adding "stabilimenta" to their webs. It's not known why spiders add these mysterious decorations, which usually involve zig-zag patterns made from opaque white threads. One idea is that they warn birds of the web's presence, preventing them from accidentally flying into them – and this is backed up by the feature's unusually low frequency on bird-less Guam.

A stubborn invader

Though brown tree snakes are thought to have been shifting the balance of Guam's ecosystems since they were introduced shortly after World War Two, this went largely undetected for at least four decades. By the late 1980s, ecologists had noticed that something was wiping out the island's birds – but no one had any idea what.

Julie Savidge, who was a PhD student at the time, decided to track down this mystery killer, which was suspected to be either a pesticide or a virus. Her research – published in 1987 – revealed that it was, in fact, down to the snakes. As island species, most of Guam's birds had no evolutionary programming that could help them to avoid the reptiles' insatiable appetite for poultry – there are no native snakes, so their ancestors were equally clueless. Consequently, when the predators arrived they found an all-you-can-eat buffet of defenceless birds which quickly became dinner.

By the time Savidge had worked out what was going on, for most avian species it was already too late. The Guam flycatcher was last seen in the wild in 1984, and this wide-eyed little ball of feathers is now considered extinct. Others have had a narrow escape.

Alamy

AlamyThe lurid ginger and iridescent green Guam kingfisher was considered extinct in the wild until earlier this year, when nine captive individuals were introduced to the Palmyra Atoll, some 5,879 km (3,653 miles) away from their natural home. The Guam rail, a flightless bird known locally as the Ko'ko', was also once listed as extinct in the wild. Today their reddish-brown bodies and houndstooth bellies can be seen scurrying around Rota and the Cocos islands, where they have been introduced.

But only in recent years have researchers begun to uncover the true scale of ecological chaos caused by brown tree snakes. The skinny reptiles are highly elusive, soundlessly slipping through Guam's forests and suburbs at night, tentatively tasting the air with their tongues to detect the scent of their next meal. But their slight appearance and the surprising rarity of sightings belies their wiles.

As it turns out, brown tree snakes are not normal predators. There are few limits on what this ambitious eater will attempt to swallow, and they regularly consume animals that are 70% of their own body weight – equivalent to a 60kg (136lb) human eating a small red kangaroo in a single sitting.

Recently, a team of scientists led by Rogers were monitoring the survival of fledgling Såli, a kind of forest starling that has managed to eke out an existence in the vicinity of Andersen Air Force Base, a US facility at the north of the island. The researchers attached radio monitors to the young birds and followed up to see what had happened to them. Often, the equipment was discovered inside the digestive systems of brown tree snakes. But there were also more grisly discoveries: dead birds that hadn't been eaten.

To their surprise, they found that many fledglings were being killed by the snakes, then abandoned: when their corpses were tracked down, they were coated in a silvery residue of snake saliva, a situation the scientists informally described as "sliming". Around half the time, the snakes were killing birds that were too large for them to swallow.

Ruth Hufbauer

Ruth HufbauerBut brown tree snakes aren't just greedy – they're also supremely effective hunters, with acrobatic skills that mean they can find prey in even the most inaccessible spaces. To help keep the remaining Såli safe from brown tree snakes, conservationists have been providing nest boxes and fortifying them with metal "baffles" – slippery metal poles, 3ft (0.9m) long and around 15cm (6in) across, which no snakes are supposed to be able to climb. Alas, they had been unaware of the crafty predator's special talent.

In 2021, a research team led by Savidge – now a professor in the department of fish, wildlife and conservation biology at Colorado State University in the US – discovered "lasso climbing", a method entirely new to science.

"Brown tree snakes can literally wrap themselves around a cylindrical baffle, hook their tail around their head and then shimmy up like a human climbing up a coconut tree," says Pollock, who describes the research as "mind blowing".

An irreversible shift

In the last few decades, conservationists and wildlife officials have used every conceivable method in an attempt to eliminate the brown tree snake from Guam – but the reptiles are winning. There have been visual searches, repellents, irritating substances, traps, poisons and deadly chemicals.

Researchers have even searched for viruses that could be used as bioweapons against brown tree snakes, to eliminate large numbers without affecting other wildlife. This method would operate something like myxomatosis in rabbits, which has been widely circulated on purpose – including in France, illegally, and Australia – with the intention of reducing their numbers. It has also caused widespread suffering, however.

But despite intense efforts, and an annual budget for snake control measures that's now around $3.8m (£2.9m), the invaders have proved to be impossible to remove in large numbers. That is, except from a few tiny patches of land. Take the Habitat Management Unit at Andersen Air Force Base on Guam. It just so happens that regular over-the-counter acetaminophen (paracetamol) is particularly toxic to brown tree snakes, with even the largest individuals perishing after an 80mg dose – around a sixth of the amount found in one standard 500mg tablet for humans. After a comprehensive programme which involved baiting them with poisoned food – along with erecting a "snake-proof" fence around the entire area to prevent it being immediately recolonised – their numbers dropped significantly on the air base.

Alas, many scientists believe that it would be impossible to remove significant numbers of brown tree snake in a similar way from Guam's forests, let alone altogether. This is despite there being some urgency to do so, because the very forest itself is at risk.

Alamy

AlamyIt's thought that roughly 70% of Guam's native trees relied on birds to disperse their seeds. But in the disconcertingly silent forest landscape today, many trees drop their fruit directly on the ground – only for it to rot where it fell. Some seeds won’t germinate at all unless the flesh has been eaten, says Rogers, while others struggle to grow in the shadow of their parent tree. With each passing year that the island's avian fruit, nut and seed-eaters don't turn up, the tree species that they used to rely on are dying out.

The forest is also starting to develop holes. In a healthy ecosystem, when a tree falls it creates a temporary gap – and this immediately becomes the site of intense competition, as different plants jostle to fill the space. "It's like if you take down a building in the middle of New York City, it's a prime real estate, there's going to be a lot of people wanting to put a building up there," says Rogers. But on Guam this doesn't happen. Without birds to disperse seeds, often there is nothing on the ground that can germinate, so regeneration is extremely slow. The structure of the forest is changing, and soon there may be no easy way back.

For now, Guam's brown tree snakes and the army of spiders they have created are safe. And their reign may last for some time yet.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.