Indigenous mothers are being 'failed' in Australia – so they are taking measures into their own hands

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCAboriginal mothers and their babies have higher death rates and poorer health outcomes than non-Indigenous Australians. New community-led services are trying to change that.

Edie recently gave birth to her fourth child. After the birth she took her placenta with her from hospital and buried it close to where she was born. It is something Edie – whose name has been changed to protect her identity for personal safety reasons – has done with each of her three children. The placenta, she says, is a baby's first home, so it is buried in what Indigenous Australians refer to as "on Country" to identify that place as the baby's home. It gives the newborns their first connection to the generations of ancestors that came before then and the land they inhabit.

The 35-year-old from Brisbane, Queensland, is one of a growing number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who are turning to a movement known as "Birthing on Country" as an alternative to standard maternal services offered by the Australian healthcare system. It is a concept that aims to better meet the needs of Indigenous Australian mothers and their babies.

"Birthing on Country connects what we know as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the modern world to what our ancestors did," says Yvette Roe, a professor of Indigenous health at Charles Darwin University, Australia. "It's a concept with key elements: when we talk about 'Country', we're talking about ancestral connection to the country where we're born. We're talking about 60,000 years of connection to the land and sky."

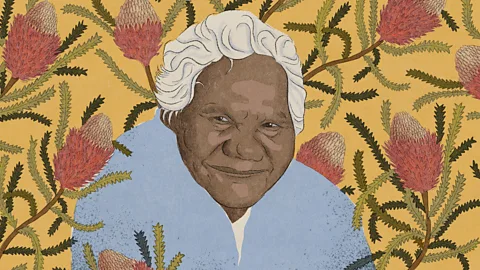

Roe, a proud Njikena Jawuru woman herself, is one of the co-directors of the Molly Wardaguga Research Centre at Charles Darwin University's Queensland campus, alongside Sue Kildea, a professor of midwifery. They are at the forefront of research, implementation and collaboration with Indigenous and non-Indigenous health and maternal services. The organisation, which was established in 2019, is named in tribute to the late Molly Wardaguga, a Burarra Elder of the Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, an Aboriginal midwife and a pioneer of the Birthing on Country movement. It was born out of a growing recognition that standard maternal care in Australia was failing to meet the needs of Indigenous women.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers are up to three times more likely to die during childbirth, and their babies are nearly twice as likely to die in their first year of life. Conditions relating to premature birth or complications during pregnancy are the major cause of infant morbidity and mortality in First Nations communities in Australia.

In 2021, preterm birth rates were 14.1% for babies born to First Nations women compared with 7.9% among non-Indigenous Australians, statistics that have changed little in over a decade.

It reflects broader gaps in the health and welfare of Aboriginal and Torrest Strait Islander people. High levels of discrimination, unemployment, poor quality housing and poor education among Indigenous Australians are among the factors that have led to worse health outcomes. It can also be difficult to access healthcare in the first place as many First Nations communities face travelling long distances to see a doctor, dentist or midwife.

Many Indigenous women live in remote areas, meaning they have to travel far from their homes to the nearest city hospitals to give birth, which can not only be expensive but also leave them feeling isolated and distressed, according to research from the Universtiy of Melbourne.

"The principle of Birthing on Country is that it is baby and woman-centred, rather than seeing birthing through a biomedical model where it is often just a transaction between a mother and a clinician," says Roe.

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCSome women also feel deeply distrustful of the modern healthcare establishment due to the chequered history of medical experiments on Indigenous Australians and children being forcibly removed from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Indeed, First Nations children in Australia are still being removed at disproportionately high rates compared to the rest of the population.

Every four years, the Close The Gap report, published by the Australian Human Rights Commission, addresses key reforms needed to address the disparity in health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people relative to non-Indigenous Australians. One of the key recommendations made in the report is the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their voices in research, policy and delivery of health services.

Birthing On Country is one attempt to do this by offering maternal care in a way that aims to recognise a woman's language and family, her health and social needs, according to its proponents.

While expecting her first child – her son – four years ago, Edie had heard bleak stories about the experiences her friends and family had had in hospital-based maternity services.

"They told me there was no sense of holistic care, and for some people that I'm close with, they felt concern around their cultural safety and the safety of their child in that hospital space," she says. "I have heard lots of firsthand experiences from many who have a distrust of the health services and the hospital system – especially with the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people having their children removed throughout history."

In response, Edie turned to her local Aboriginal health service to ask about her options.

"I wasn't sure exactly what I wanted, but I knew I wanted something culturally appropriate," she says. She eventually found the Birthing in Our Community (BiOC) programme, a multi-agency service operating in Queensland and New South Wales.

Since launching in 2003, over 1,000 women have used BiOC services, which are run by Mater Mothers' Hospital in South Brisbane and two First Nations community-controlled health services: the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane. Together they offer a system of maternal care that depends on a skilled First Nations workforce, multi-agency partnerships (community organisations, health practitioners, social workers), and a community hub or centre where these services are delivered.

All three of Edie's children have now been born within the BiOC programme. "It's been the most positive, beautiful experience, free of birth trauma," she says. "That entirely factored into my love and want for more children, which I attribute to BiOC."

Edie's care was provided by a team that included an obstetrician, an Indigenous family support worker and one of four midwives. She says that her team of carers was primarily women, which gave her an additional level of assurance. "This is what women have been doing for millions of years together with other women," she says. "Birthing was a ritual, and it was always conveyed to me that it was beautiful."

A vital aspect of BiOC is its holistic, sensitive approach, says Kristie Watego, services development officer with the Institute of Urban Indigenous Health in Brisbane. Some of the women she deals with have difficulties that go beyond just their health, such as experiencing domestic violence, and so those too need to be considered.

"We provide great clinical care but first and foremost, we provide connection and being together, teaching mothers to advocate for themselves in a medical system which constantly overlooks them," she says. "Telling a woman in a domestic violence situation to eat better during her appointment is useless. We need to ask, 'what's going on for you and how can we support you?', then we get into the clinical matters. Sometimes women say they're not in a domestic violence situation, but their partner controls all the money, so it's about saying, 'let's have a yarn about this. We'll walk with you and we'll help you through this.'"

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCWatego had worked in corporate management roles for 18 years before giving birth to her first two children. Her first child was born at the Murri Clinic, part of the Mater Mothers' Hospital, where she received care in what was the first iteration of the BiOC model. Watego's third child was born through the programme in May 2018 after she had decided herself to work in maternity care.

"A lot of our workforce [at the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health] were clients of the programme and we feel that those who are best placed to design the BiOC programme are those who have used it," she says. "We're employing our community and using their strength and knowledge to design and enhance the programme.

"The families that we work with now are people we grew up with. We have strong connections and we have a community obligation. The majority of our team are Indigenous and in caring for First Nations families, we see them as extended family. My mother has nine grandchildren born through this programme, so it has to be the best. This has to be somewhere that women feel safe, not judged, and not fearful of this system."

There are other benefits too. Owing to fewer interventions and procedures along with lower levels of neonatal admissions, Birthing on Country models have been found to be less expensive than standard maternal care. In a comparison of First Nations mothers experiencing standard care in a Brisbane maternal hospital versus community-led Birthing on Country, there was a 5.34% reduction in preterm births for Indigenous families and a saving to the health system of A$4,810 (£2,170/$2,700) per mother-baby duo.

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC"We know that the current medical system is failing First Nations women," says Roe. "There are so many clinical interventions, caesarean births and the use of forceps. We know that when you have a Birthing on Country service, there's less likely to be interventions, mothers are more likely to have a vaginal birth and less likely to have medication and drugs, and the baby is [more likely to be] a healthy weight. It's saving the system so much money."

If these findings were extrapolated nationally, then based on the 18,086 First Nations babies born in 2019 in Australia, there is potential to reduce the number of preterm babies each year by 965 and save A$87m (£45m/$56m) in Australian healthcare expenditure, according to one recent assessment.

Roe says that the reason for fewer preterm births is a result of intensive pre- and post-birth care.

"A woman gets her midwife and a suite of support services and primary healthcare services, so as she transitions into the hospital that support is still there," she says. "It's about addressing lifestyle choices, and all the maternity care services that happen before delivery. So, addressing smoking, financial distress, homelessness or nutrition, for example. The impact of women engaging early with trusted carers, receiving more antenatal care and check-ups, had a major effect."

More like this:

Trust and engagement was particularly important for Edie when she had her first child. She recalls attending a breastfeeding class in hospital that was not specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers.

"I was trying to breastfeed for the first time," says Edie. "My baby at that time couldn't latch, and I was pointed out as an example of a mother whose baby wouldn't latch. So, I had the teacher bringing the other women over to observe my breast and the baby not latching. I still remember tears landing on the floor, but I was sure I would breastfeed. I knew it would happen."

Soon after she arrived home, an Aboriginal liaison staffer – "an older auntie" – came to visit Edie at home. "She said, 'lay down with your baby and he'll feed'. That Blackfella way, that nurturing, felt so natural and I needed that reassurance. It felt empowering to me as a mother."

So far, Birthing on Country projects – collaborative partnerships between Indigenous community organisations and hospitals – have been established in New South Wales, Queensland, and the Northern Territory. NSW-based Waminda Health Service in Nowra was granted A$22.5m (£11.7m/$14.6m) over a three-year period for the construction of a Birthing on Country Centre of Excellence in May last year. It is expected to open in mid-2025.

Investment like this to expand Birthing on Country initiatives means that more women like Edie could benefit from the support and culturally sensitive care that she received during the birth of her children.

What it comes down to, Edie says, is that "Blackfella way is different when it comes to childbearing and child rearing. Some people feel safe in that medical model, but BiOC has a broader understanding around family, kinship and the strength of ancestors before us."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.