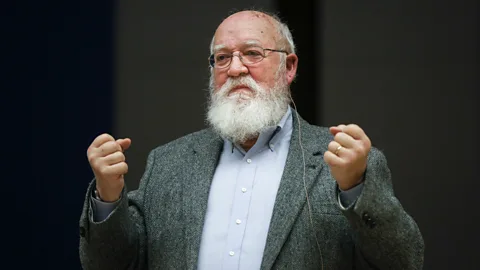

Daniel Dennett: 'Why civilisation is more fragile than we realised'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBefore his recent death, the influential philosopher Daniel Dennett spoke to the BBC about his lifelong quest to understand human experience – and why he saw new dangers from AI.

The philosopher Daniel Dennett, who died at the age of 82 on 19 April, was among the sharpest and most prophetic minds of the last half-century. Throughout his life, he dared to tackle some of the biggest questions about the human mind and consciousness. His career saw him publish over a dozen books, make major contributions to fields ranging from cognitive science and philosophy of mind to evolutionary theory, and become an ardent advocate for rationality and scepticism.

In December 2023, I spoke to him for several hours about his recent memoir, I've Been Thinking, as well as his life and work. He was still passionately engaged with the questions of truth, cognition and technological possibility that first fascinated him as a doctoral student at Oxford in the 1960s – and still willing to pick a fight in the service of rigorous thought.

In particular, our conversation focused on the grave risks posed by artificial intelligence. His warning was not of a takeover by some superintelligence, but of a threat he believed that nonetheless could be existential for civilisation, rooted in the vulnerabilities of human nature.

"If we turn this wonderful technology we have for knowledge into a weapon for disinformation," he told me, "we are in deep trouble." Why? "Because we won't know what we know, and we won't know who to trust, and we won't know whether we're informed or misinformed. We may become either paranoid and hyper-sceptical, or just apathetic and unmoved. Both of those are very dangerous avenues. And they're upon us."

Science fiction philosophy

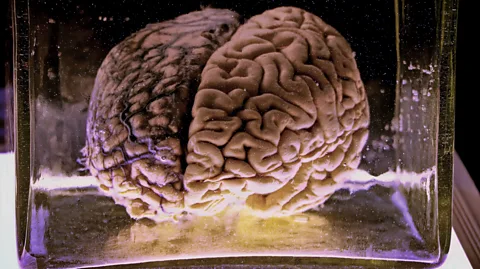

To understand Dennett's argument about AI – and what made him such a deep and original thinker – it's worth looking back to one his most unusual academic papers. In 1978, he published Where Am I?, which took the form of a science fiction short story featuring his own brain in a vat.

"Several years ago," the story begins, "I was approached by Pentagon officials who asked me to volunteer for a highly dangerous and secret mission." Thanks to an accident during a classified research project, a drilling device bearing an atomic warhead had got stuck a mile underground, beneath Tulsa, Oklahoma. They needed him to help retrieve it. More precisely, they needed his body. In order to avoid the neuron-damaging radiation being emitted by the device (plausibility isn't a necessary feature of philosophical science fiction), his brain would be surgically removed and hooked up by radio transceivers to his body. He could then remotely control it without risking exposure.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe question behind Dennett's delightful fantasy was this: assuming the procedure succeeded, and his brain continued to control his body and receive inputs via its sensory organs, where would Daniel Dennett be? In the story, he imagines his body walking into the room where his brain floats within a reinforced vat, then sitting down and looking at it.

The scene was recreated for television in a 1988 documentary by Dutch director Piet Hoenderdos – in which Dennett played himself (with gusto). It's surely one of the only cases of an academic paper receiving such an adaptation. "Well, here I am sitting on a folding chair, staring through a piece of plate glass at my own brain," the flabbergasted Dennett declares. "But wait… shouldn't I have thought, 'Here I am, suspended in a bubbling fluid, being stared at by my own eyes'?"

The second of these thoughts proves even harder to maintain than the first. And the thought that follows from this is that it's impossible ever to be certain where "I" am – or even what the word "here" means – purely on the basis of personal experience.

"How did I know where I meant by 'here' when I thought 'here'?" he continues. "Could I think I meant one place when in fact I meant another?" No matter what he may believe about his own location or mental state, such beliefs offer no special guarantee of their own accuracy. The external view of events, not the internal, is the one that matters: the facts on the ground, not how this ground appears to the person standing upon it (or floating in a vat, as the case may be).

Contrary to centuries of philosophical tradition, he proposed, we have no special knowledge about the working of our own minds – while the sense that our "self" is a unified, coherent entity is merely a marvellous, evolved illusion.

As he put it in I've Been Thinking, "there is little I can know for sure from single-handedly introspecting my own mind." But there is much to be learned by "studying the minds of others scientifically" – so long as this entails a rigorous scepticism about even the most plausible of intuitions. The truth won't free you from cognitive constraint, because no such thing is possible. But it may, if you're careful, teach you about the kinds of freedom worth wanting.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis brings us back to a technology uncannily capable of inverting the scenario at the heart of "Where Am I?": generative AI. It has the capacity to conjure convincing human simulacra from trillions of bytes of data; and, by doing so, to upend centuries of assumptions around truth, identity and our shared experiences of reality.

Given just 30 seconds of moderate quality video, for example, freely available AI services can now create an artificial version of any speaker – or a wholly fictional person – and have them say anything whatsoever. Leaders like the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have already used AI tools to create versions of themselves speaking fluently in regional languages, the better to win votes, with similar approaches being deployed in Indonesia and Pakistan. In July 2023, crude deepfake videos of female opposition leaders in Bangladesh, purporting to show them in bikinis and swimming pools, were rapidly debunked but still shared widely. And much more is coming our way. With 2024 set to be the biggest year for elections in history (no less than half the world's population will be visiting various polls), it has never been easier for the information influencing human decision-making to be manipulated – or for our everyday intuitions and inclinations to be subverted.

Indeed, there's every reason to think that, with enough data, it might soon be possible to create a convincing facsimile of a person: an entity who could conceivably pass for a politician – or you or me – not only in a pre-recorded performance but also in everyday conversation.

Presciently, Dennett imagined this scenario decades ago. In the science fiction story in Hoenderdos's documentary, scientists create an extra Dennett: alongside the original brain in a vat, his mind is duplicated as a "digital twin". They compete to gain control of his body. In this scenario, the question of whether someone actually is somewhere – or has said or done something, or even exists – becomes even more fraught.

To see how close reality has already come to fiction, consider the case of the Luciano Floridi Bot, an AI-driven imitation of another leading philosopher of technology, "designed to answer questions and write texts emulating Floridi's ways of thinking and his style of writing". It's both a fascinating pedagogical tool and a case study of how, in an age of AI, our ideas and our identities can literally start to take on lives of their own.

For Dennett, there was something troubling about the very fact of our obsession with human-seeming AI. While complete facsimiles of the human mind may not be imminent, the way we're using AI to impersonate human beings has, he told me, already put us on a dangerous trajectory. He called such AIs "counterfeit people", and told me that rolling out such entities en masse constituted "mischief of the worst sort": a form of "social vandalism" that should be addressed by law. Why? Because, if convincing digital representations of humans can be created at whim, the entire business of collectively assessing other people's claims, experiences and actions is put at risk – not to mention essential social infrastructure such as contracts, obligations and consequences. Hence the need for legal prohibitions, a case he made at length in a May 2023 article for The Atlantic. "It won't be perfect," he told me, "but it will help if we can make it against the law to make counterfeit people. We can have stiff penalties for counterfeiting people, same as we do for counterfeit money… we should make it a mark of shame, not pride, when you make your AI more human."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere's an irony, here, in the fact that Dennett spent decades arguing against those trying to carve out some elusive category of "humanness" that only our minds can possess. A thoroughgoing materialist, he repeatedly made the case that, as he put it in his 1995 exploration of evolutionary theory, Darwin's Dangerous Idea,"all the achievements of human culture – language, art, religion, ethics, science itself – are themselves artifacts… of the same fundamental process that developed the bacteria, the mammals, and Homo sapiens. There is no Special Creation of language, and neither art nor religion has a literally divine inspiration."

More like this:

Humanity's emergence from unthinking matter is marvellous, he argued, but not miraculous. Even minds as remarkable as ours are ultimately the products of an assortment of uncomprehending modules, themselves composed of cruder components, connected in unbroken sequence to the first forms of life.

It follows from this that, in principle, there is nothing preventing the algorithms of artificial intelligence from approaching or exceeding our own capacities; or from humans augmenting and re-engineering their minds through artificial means. Indeed, some of Dennett's most important early work entailed defending computation's power and potentials against those who, like the philosopher John Searle, claimed that mere calculation could never give rise to phenomena like consciousness. For Dennett, there was nothing "mere" about calculation or algorithmic processes: it was only ever a question of scale and complexity.

In this sense, the achievements of modern AIs – from their linguistic prowess and mastery of games like chess and Go to their ability to pass legal and medical examinations – are an ongoing vindication of Dennett's insistence that human-level competence can arise from wholly uncomprehending processes (not to mention that, in our case, it did).

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring our conversation, however, he was also at pains to highlight the gulf between current computational architectures and humans' analogue complexities. It's dangerous to obsess over whether AI will achieve "general intelligence", with all the cognitive flexibility of a human being, let alone something greater. Long before anything like this happens, he noted, we will need to deal with the emergence of "extremely manipulative" autonomous agents – and these will pose a far greater threat than hypothetical superintelligences ("forget about that!"). Why? Because, much as social media has proved an evolutionary hothouse for content able to exploit human vulnerabilities, the same dynamics favour both AI-generated content and AIs able to deploy an enticing combination of persuasion, seduction, shock and flattery.

From flawlessly glamorous artificial influencers to deepfake pornography, from endlessly empathetic companions to romantic scams, human loves and longings are a fertile field for the refinement of manipulation. We may not (yet) be brains in vats. But what we see, believe, belong to and do is increasingly interwoven with countless information systems; and many of these are more adept at delivering persuasion and plausibility than truth.

None of this is to deny the power and potentials of technologies like AIs, or the countless ways in which they may enhance humanity's scope and self-knowledge. But it is to make the case that, as Dennett put it, AIs are likely to "evolve to get themselves reproduced. And the ones that reproduce the best will be the ones that are the cleverest manipulators of us human interlocutors. The boring ones we will cast aside, and the ones that hold our attention we will spread. All this will happen without any intention at all. It will be natural selection of software."

Neither a human nor a machine-made masterplan is required for harmful scenarios to unfold. As Dennett's 2017 book From Bacteria to Bach argued, "once the infrastructure for culture has been designed and installed [i.e. evolved in human minds]… the possibility of parasitical memes exploiting that infrastructure is more or less guaranteed." In evolutionary terms, our minds aren't devices fine-tuned for differentiating truth from lies. We are partial, passionate, tribal creatures: social animals linked by bonds of love and loyalty that both define our humanity and make us painfully vulnerable.

What is to be done? Thankfully, another defining feature of human thought is our capacity for reflecting upon precisely these limitations: for redressing, collectively and incrementally, the blind spots of personal perception. "What you want," Dennett told me, "is your thinking to be determined by the truth about what's out there. You want to be compelled by the good evidence there is out there for how the world is. But you also want to have the elbow room to reconsider, and reconsider, and reconsider further: your prospects, your projects, your goals. You want to be a higher order, intentional system that reflects upon means and ends and goals."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis is the scientific method in microcosm, with a flavour of humanist freethinking. The "freedom" to act on the basis of manipulatively inaccurate information is no freedom at all. By contrast, actions determined by "the good evidence that is out there" are emancipatory: open to the complexities of actuality rather than snared by untruths.

To extend the thought experiment of "Where Am I?", imagine what would happen if your brain were placed in a vat and then – without your knowledge or permission – hooked up to a simulated version of reality. Within that virtual realm, you might still possess certain freedoms. In the context of the external world, however, you would be both trapped and deceived: cut off from every meaningful form of understanding and action. (Read more: The philosopher rethinking the definition of reality.)

Although it may seem purely a matter for speculative fiction, a version of this scenario plays out every time someone takes a false claim to be the literal truth – or an artificial entity to be a human. From conspiracy theories to totalitarian propaganda, from fabricated evidence to ersatz humans, reality-rejection is a booming business. And there's nothing inevitable about the endurance of tolerance, scepticism or reasoned debate in a world suffused with such things. Civilisation, Dennett told me, "is more fragile than we realised" – and all the more precious for this. Despite its conflicts, injustices and hatreds, we inhabit an era where it is possible for a large proportion of humanity to "trust each other, have long-term projects, travel freely, raise families, live with very little fear. That's just wonderful. And we should preserve that. That social structure, really, at all costs." This is the great danger of AI large language models and counterfeit people alike: "that they will destroy the trust that we have engendered over thousands of years".

Sign up for Tech Decoded

For more technology news and insights, sign up to our Tech Decoded newsletter. The twice-weekly email decodes the biggest developments in global technology, with analysis from BBC correspondents around the world. Sign up for free here.

Despite all this – and his reputation for unyielding reasonableness – Dennett made it clear to me that he had no interest in transcending the limitations of human nature. Love and loyalty weren't, for him, biological baggage we would be better off moving beyond. Rather, they were motivating forces of the most profound kind: wellsprings of purpose and goodness, so long as they could be unshackled from egotism and hatred. "Looking out for number one is a perfectly good agent rule. But number one can be understood very broadly. Number one can include your children, an idea, guitar playing, the Chicago Bears. Number one can be whatever you want it to be. That's what you care about the most. That's what you're going to protect. And this is obvious. If somebody wants to extort you, they don't have to threaten you. They just have to threaten what you love."

Biology is where it all begins and ends: the evolved, astonishing pattern of our emergence alongside every other form of life; the limitless complexities we are capable of conceiving via culture, language and computation; our common existence as creatures of flesh and blood. "My children are both adopted," Dennett told me at the very end of our conversation. "But I love them with the intensity of any biological dad. I can remember a moment in the early life of our eldest, when she was a little girl, maybe two years old or less, when I detected some possible threat on a playground or something, and it suddenly struck me, 'Oh, my goodness, I think I would kill to protect this child.' And it scared me, almost. But it also thrilled me, because it was a recognition of the intensity and depth of emotional attachment. And that's what life is all about."

*Tom Chatfield is a British author and philosopher of technology. His most recent book, Wise Animals (Picador), explores the co-evolution of humanity and technology.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.