Eclipses do odd things to radio waves. An army of amateur broadcasters wants to find out why

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontDuring the American solar eclipses of October 2023 and April 2024, hundreds of radio amateurs will take to the airwaves. Their goal is to help scientists investigate what happens to radio signals when the Moon blocks the Sun.

It's the huge tower in his back yard that gives Todd Baker's hobby away. Bristling with antennae, the 30m (100ft) structure is taller than many of the mature trees nearby. Baker, an industrial conveyor belt salesman from Indiana, goes not just by his name, but also his call-sign, the short sequence of letters and numbers that he uses to identify himself over the air: W1TOD. He is a member of the amateur radio, or ham radio, community.

"You name it, I've been in it," he says, referring to different radio systems, including citizens band, or CB radio, that he has dabbled with over the years. "Communications were just plain-o cool to me."

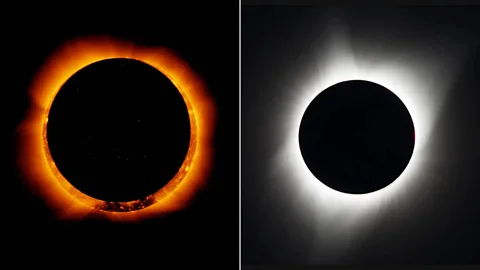

Now, he dabbles in celestial citizen science, too. On 14 October, he and hundreds of other amateur radio enthusiasts will deliberately fill the airwaves during an annular solar eclipse, as it crosses the Americas. They'll do it again next April, when a full solar eclipse becomes visible from Newfoundland to Mexico.

Why? Solar eclipses are known to affect radio transmissions, and Baker is planning to take part in a giant experiment designed to monitor how cosmic events affect radio broadcasts.

Byron Maldonado

Byron MaldonadoOn his 7.25 acre (3 hectare) plot off a highway south of Indianapolis, Baker's collection of spiky antennae pointing in various directions allows him to make transmissions across the US and much further afield. He has transmitted his voice to the other side of the world and had conversations with fellow amateur radio enthusiasts in Europe and even New Zealand, 13,000km (8,000 miles) away.

One of the antennae in Baker's garden is specially angled, he says, so that it transmits a radio signal that initially stays low to the ground. But eventually that signal will head off towards space. "As it reaches the ionosphere," says Baker, "it'll make a hop. It'll bounce."

This phenomenon, in which radio waves are purposefully reflected off some of the atmosphere's upper layers, vastly extends the distance over which radio operators can communicate. It's called the "skywave effect" and it's how the first radio broadcast was sent across the Atlantic Ocean in 1901.

It means that the curvature of the Earth is surmountable. Radio transmissions can zigzag up and down, bouncing between the ground and ionosphere, which sits at an altitude of roughly 80-650km (50-400 miles). You could say that a person's voice, transmitted in the form of electromagnetic waves, literally touches the sky during long distance broadcasts that rely on this effect.

"The fact that you can pick up radio signals from the other side of the Earth," says Cathryn Mitchell, professor of radio science at the University of Bath, "it is really quite astonishing."

You may also like:

The really amazing thing is that the skywave effect is not stable – and scientists still don’t fully understand it. The ionosphere is weird. It fluctuates, it moves around, expands and contracts, and is far from uniform. It is sometimes full of waves itself, says Mitchell, which ripple away during sunrise and sunset – almost like throwing a stone into a pond.

The Sun's presence or absence is one of the reasons for this. In the daytime, the ionosphere thickens because sunlight strikes atmospheric gases, ionising them to produce electrons. At night, the collisions lessen, and the ionosphere's lower layer disappears. This night-time thinning allows radio waves to travel much further, because they reach higher altitudes before the electrons bounce them back towards Earth. It is why people have long been able to pick up distant radio stations in the early hours.

THE RULES OF RADIO

To find other "ham" radio amateurs, sites like QRZ.com serve as a kind of phone book. After connecting, operators sometimes send each other QSL cards – like postcards – about their broadcasting station. (QSL is code for "I confirm receipt of your transmission".)

Ham radio enthusiast Todd Baker has encountered many personalities over the airwaves, from US apocalypse preppers to Ukraine citizens caught in the war with Russia. It's an unwritten rule to avoid politics or religion, though. "Some people go ahead and do it, I try to avoid it," says Baker. "If you disagree or agree with, say the President or the Vice President of the United States, it's still an office that should be respected."

It's not all conversation, though. In the US, some amateur volunteers lend support to local authorities in emergencies. During the eclipses, they'll track traffic issues, cell phone problems and other hiccups.

The ionosphere's weirdness requires investigation on a large scale. An eclipse provides the perfect opportunity to bring together lots of people in order to test our understanding of what happens to it as it fluctuates, and also at a convenient time – during daylight hours. Plus, eclipses aren't the same as night-time in terms of how they affect ionisation activity. The shadow cast by the Moon is particular – a point shape that travels quickly across the Earth's surface. During an eclipse, therefore, unexpected things might happen to the ionosphere, which scientists are keen to observe.

Enter the amateur "ham" radio community, whose members have signed up to a citizen science collective called HamSCI. As the two upcoming American eclipses approach, hundreds of volunteers will begin broadcasting, so they can track their experiences and share them with scientists. Baker is among the volunteers. "They want to be able to hear how signals come and go," he explains. "No other times do you have the ability to shut the Sun off and turn it right back on."

Leading the experiment is Nathaniel Frissell, a space physicist and electrical engineer at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania, who founded HamSCI. Via Zoom, he explains why there's still so much to learn about the ionosphere. He shows me an animation featuring the ionosphere figured as a curved, fuzzy layer neatly sheltering the ground below. "Do you see how smooth this ionosphere is? In real life, the ionosphere is not that smooth," he says. There are transient lumps and bumps, for want of a better phrase, that scientists are still not good at predicting.

During the upcoming eclipses, Frissell – whose own call-sign is W2NAF – will gather data from, among other sources, individual ham radio operators, volunteers who plan to use highly sensitive transmitting equipment during the events, and online databases that track public radio activity. It is an experiment on a scale that simply would not be possible with standard academic instrumentation alone, he stresses – there's just not enough of it over a wide enough area. The upcoming experiments follow a similar effort during a total solar eclipse above the US in 2017. Baker took part in that, too – he's kept the local newspaper cutting with his picture in it.

Byron Maldonado

Byron MaldonadoUnderstanding the ionosphere matters because, during military or disaster response operations, for example, precisely targeted radio communications can make the difference between life and death. It's crucial for radio operators to know how best to set up their transmission for a successful broadcast. Also, ionospheric variations sometimes affect satellites, says Ruth Bamford of RAL Space, based at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, which is part of the UK's Science and Technology Facilities Council.

Solar flares, for instance, cause the ionosphere to expand, which increases the drag on satellites orbiting the Earth, meaning they might have to get boosted back up to a higher altitude lest they plummet towards the ground.

Bouncing radio waves off the ionosphere is like probing a giant, ever-shifting sea of ethereal matter. "It's quite a hard thing to do," says Bamford. "You've got a mirror up there that is changing with the Sun."

QUIET AIRWAVES

Ham radio appears to be in decline in many parts of the world, including in the UK and Australia. And while the Covid-19 pandemic prompted a ham radio renaissance in places such as Japan, the outlook in the US isn't great, says Michelle Thompson, who has studied the demographics of ham radio operators there. "We're treading water," she says, pointing out that licensee numbers across the states are either level or in a slight decline. Plus, the hobby has become less diverse, at least in terms of gender representation, she adds: "We're kind of in trouble here. Radio seems to be taken for granted."

Bamford praises the radio volunteers. She enlisted similar help herself, back in 1999, during a rare total solar eclipse visible in the UK – the next one won't occur until 2090. In 1999, volunteers tracked variations in signal strength during the eclipse and many recorded a significant spike, revealing how radio transmissions could briefly travel much further than they normally would in the daytime. Bamford and her colleagues also asked members of the public to tune their home radios to a frequency used by a Spanish broadcaster. Normally, this station wouldn't have been audible on domestic radios during the day but many hundreds of people in the UK reported hearing the broadcast fade in and then out again as the eclipse came and went. Given our imperfect understanding of the ionosphere, there could be more surprises during the upcoming eclipses, she says.

"Amateur radio is a very, very good vehicle for this," argues Michelle Thompson, chief executive of the Open Research Institute, a non-profit organisation involved in amateur radio research and development. Thompson's call-sign is W5NYV.

Radio operators who make transmissions during the eclipses will act as a kind of giant "distributed receiver", she suggests. And as radio equipment improves, every time an experiment like this is carried out, there's more opportunity for finer discoveries about variations that occur in the ionosphere.

As for Baker, he is looking forward to reading the results from the upcoming eclipses. The data could improve his ability to make successful broadcasts at certain times of the day, he suggests. Many ham radio operators are keen to hone such skills. Baker enjoys setting himself challenges such as making long-range transmissions using very low-powered signals. Or throwing a portable antenna into a tree and broadcasting from scenic spots on holiday.

The attraction is, in part, the uncertainty of what will happen next. There's something about firing up a radio, getting your signal to bounce off the ionosphere, and virtually bumping into complete strangers across enormous distances that can't compare to just tapping out a message to one of your contacts on a smartphone app. "It's unscheduled communication, just totally serendipitous, opportunistic," says Thompson. She's made many friends through her broadcasts. It even led to her presenting research at a conference in Japan.

Unlike picking up a telephone, it's more akin to heading out onto the ocean in a boat, she explains. You have to understand and pay attention to big forces of nature, the weather, even the invisible turbulence of the atmosphere, in order to get where you're going.

"It makes for an adventure every single day," she says. "You never know who you're going to be able to talk to."

--