The 'cosmic dust' sitting on your roof

Alamy

AlamyIt comes from outer space. Mary Westover talks to the scientists searching for hidden micrometeorites in Antarctica and on cathedral roofs.

It's in the dirt on the ground, the debris on your roof, and the dust that tickles your nose – tiny pieces of "cosmic dust", everywhere.

These microscopic particles from outer space are micrometeorites – mostly the debris from comets and asteroids – and they have settled all over our planet.

The dust, scientists are learning, contains clues to how Earth and our Solar System formed. But while the stuff is everywhere, finding in amongst the dirt and debris is far from straightforward.

You may also like:

Most cosmic dust probably comes the Zodiacal cloud, an interplanetary dust cloud that orbits our Sun. Earth passes through this cloud, and the cosmic dust is swept up by our planet's atmosphere.

Once the particles settle to the ground, they can be found anywhere; they could be sitting on your clothes right now. But despite their widespread presence, finding cosmic dust isn't easy.

The Infinite Monkey Cage

This story is adapted from an episode of The Infinite Monkey Cage on BBC Sounds. Listen to more episodes.

One place that the particles show up more easily is Antarctica. Around a decade ago, Matthew Genge at Imperial College London spent seven weeks searching for and collecting dust there, as part of the Antarctic Search for Meteorites program (Ansmet), a US-led field-based science project that recovers meteorite specimens. Since then, he's spent years analysing the materials he found on this trip.

"Sometimes I feel like it's a bit like the emperor's clothes, I've spent my life studying something no one can see," Genge says.

Antarctica may seem like a long way to travel just to sweep up some dust, but it's the perfect place to go if you're looking for cosmic material. "It's the driest place on Earth because all the water that is there is ice. And that means that the cosmic dust and meteorites last a long time," Genge says.

Matthias van Ginneken

Matthias van Ginneken"You can imagine, if a meteorite falls in the UK, try finding it in the grass. It's literally looking for the cosmic needle in the haystack," says Genge.

Samples collected from Antarctica are more likely to contain cosmic material and will be a lot cleaner than samples collected from environments with a lot of people, cars, and rain that can wash the dust away. Out of the 5kg (11lb) of dust that Genge collected in Antarctica, he found thousands of micrometeorites.

Graze the roof

The downside to collecting dust from Antarctica is the cost and complications of travelling there. That's why Penny Wozniakiewicz of the University of Kent in the UK has focused her research closer to home. The key is to collect material from a fairly undisturbed spot.

Wozniakiewicz scours the rooftops of old cathedrals in the UK as the source of her samples. As of this month, she has collected dust and debris from the cathedrals in Canterbury and Rochester in the south of England.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe focused on these roofs because they are old and more untouched than modern buildings. What's more, historic buildings like cathedrals usually have well-kept records that indicate when maintenance and cleaning have been done. That makes it easier to determine how long cosmic dust has been collecting and gives researchers insight into what other particles might be present in the dust they collect. This allows them to more efficiently remove the Earth stuff, and focus on the space stuff.

Dust in space

Soon we may be able collect cosmic dust far away from Earth. Nasa's Lunar Gateway is set to be the first extraterrestrial space station. It will orbit our Moon and serve as a base for deep space exploration. Gateway could also collect interstellar dust, which would be much less likely to be contaminated by human activity and debris from spacecraft than dust orbiting around Earth. These samples of interstellar dust could lead to deeper insights into the origins of the Universe and the composition of celestial bodies.

The sorting process can be tedious. First, the material must be cleaned, because the rooftops of buildings are not as pristine as Antarctica. The clean material is then put through sieves, to separate out the pieces that are small enough to be cosmic dust and big enough to be studied. What's left is put under a microscope.

A scientist with as much experience as Wozniakiewicz can identify a potential cosmic particle by its shape, but determining the elemental composition confirms it. Unlike regular dust, the cosmic dust bears the unmistakable signs of radiation exposure from the Sun and the wider galaxy: radioactive isotopes that decay very rapidly.

Wozniakiewicz and her joint lead on the cathedral project, Matthias van Ginneken, have plans to visit the rooftops of several other cathedrals with their vacuum collection bags. And eventually they hope to display what they have found to the public in a unique, artistic way. They hope to turn detailed scans of cosmic dust into much bigger 3D models to be displayed at the cathedral in which they were found.

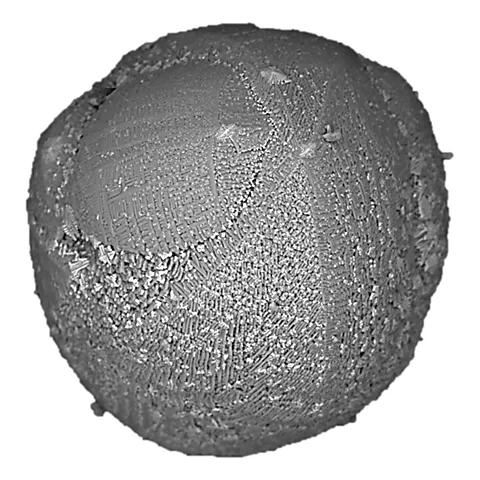

M. van Ginneken/RAS/L. Folco, University of Pisa.

M. van Ginneken/RAS/L. Folco, University of Pisa."The idea is to actually take something you can barely see on your finger, and then make it much bigger so you can hold it in your hand," says Wozniakiewicz.

Each year, approximately 100 billion particles of space dust land on Earth, carrying secrets from asteroids and offering glimpses into the formation of planetary systems. These micrometeorites not only contain water but also organic molecules; they potentially served as the building blocks for life on Earth. We know that water and life both came after the formation of our planet, so had to come from outer space – possibly from icy asteroids.

Cosmic dust could, therefore, tell scientists about the intricate relationship between these celestial bodies and Earth. It acts as a bridge, connecting us to the wider cosmos.

--