Mission to the Moon: Who will win Russian and India's race to the lunar South Pole?

Alamy

AlamyTwo spacecraft – one built by India and the other by Russia – are hurtling on missions towards our Moon by very different routes. But does it matter which touches down first?

Right now, a mini space race is afoot. Two spacecraft, one Russian and the other Indian, are headed for the South Pole of the Moon – where no lander has ever successfully gone before. The Russian and Indian vehicles are on competing quests to search for water ice and potentially useful minerals that might be tucked away in the lunar dust.

Such was the timing of the crafts' departures that they are due to reach their destinations around the same date. No one planned this showdown, it is simply a curious twist of fate – but one that has got the world watching, and wondering: who will get there first?

Worries around the Moon

The timing of Luna-25's arrival seems to have worried the Indian Space Research Organisation, who two days before Russia's planned launch issued a public statement assessing the increasingly cramped orbital space around the Moon. It warned that there are already six active spacecraft orbiting the Moon – four belong to Nasa, one is from South Korea and another from an earlier Indian mission – but added that with the arrival of Luna-25 followed by nine further spacecraft over the next two years there will be a growing risk of collisions. It said that its own Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft, which launched three years ago, has already had to perform three collision avoidance manoeuvres to prevent close encounters with Nasa's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter.

For decades, our reading of things that happen in space has been unavoidably shaped by the original space race of the 1960s, in which the United States and the Soviet Union vied to put a human being on the Moon. Despite the Soviet Union becoming the first nation to put a satellite in Earth orbit, launch a human into space, and land an uncrewed spacecraft on the Moon, the US grabbed the biggest prize of all when the Apollo 11 mission carried astronauts to the lunar surface. Their adventure was broadcast on TV screens around the world and it was followed by further crewed Apollo missions in subsequent years, with the last taking place in 1972. More than 50 years later, the US remains the only country to have achieved a crewed Moon landing.

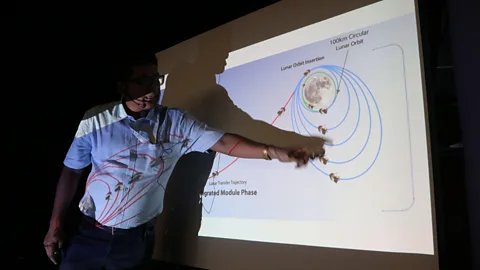

The Indian lander, Chandrayaan-3, blasted off from Earth on 14 July, packed with a payload of scientific equipment as well as a small, six-wheeled rover for exploration of the lunar surface. It's due to touch down on the lunar surface on 23 August after first sling-shotting around the Earth a few times and spending several weeks orbiting the Moon in preparation for the landing. The Russian lander, meanwhile, Luna-25, departed our planet only recently, taking off just after 2am Moscow time on 11 August (11pm GMT 10 August). It is taking a much faster, more direct route to the Moon and could reach the surface in as little as 10 days post-launch, on 21 August. Officials at the Russian space agency Roscosmos have made no secret about their desire to be first to make a soft landing at the Moon's South Pole.

But Luna-25's journey might take slightly longer than that, meaning Chandrayaan-3 could arrive on the Moon first, in the end. Slow and steady could win this race.

The missions, however, reflect the renewed interest in the Moon for space exploration. The recent discovery of significant pockets of water ice on our nearest celestial neighbour has excited scientists because hydrogen in the water could potentially be extracted to make rocket fuel at a future Moon base. Plus, the water might even be drinkable after treatment.

The so-called race between Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 encapsulates a new era of lunar exploration, in which nations including the US, Israel, and China, as well as private companies, are targeting the Moon with spacecraft and forthcoming crewed missions. For many, it's just friendly competition. And yet, a fresh chapter of human exploration is at stake. The small steps taken by individual landers and crewed missions could add up to giant leaps in conquering the Solar System in the coming decades and centuries. Who gets there first really could matter.

"It's turned out to be more of a coincidence than anything," says Wendy Whitman Cobb, professor of strategy and security studies at the US Air and Space Force's Air University, referring to the timing of the Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 missions. "But it is a very interesting coincidence." Luna-25's launch has been repeatedly delayed – it was originally scheduled for 2021.

India has a "leg up", she says, since its spacecraft is already in orbit around the Moon. The Russians probably feel some pressure to get there first, though, she suggests, given their more direct route. Chandrayaan-3 is twice as heavy as Luna-25 and was also launched using a much less powerful rocket, meaning it needed to build up speed by taking large elliptical orbits around the Earth before it could swing out towards the Moon itself. Operators of the two craft will have to assure themselves of the performance of each vehicle before starting the touchdown procedure. Unexpected malfunctions could push the attempt back or scupper it entirely. They won't know how it's going to go, really, until they get there.

National pride will probably be a factor in pushing ahead wherever possible. Russia is arguably hoping to prove its continued capabilities in space given that the country's space programme has been affected by sanctions following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. "Their space industry has really, really suffered," says Whitman Cobb.

But it's hardly a race to the Moon, as such, for Russia, says Stefania Paladini, who studies the space industry at Queen Margaret University in the UK, because the former Soviet Union succeeded in putting multiple landers and even rovers on the Moon 50 years ago. In that sense, the Russians won the race long ago and, clearly in homage to that, the name Luna-25 harks back to the last Russian lunar mission, Luna 24 in 1976. The Soviet Luna 1 space probe is regarded as the first spacecraft to reach the Moon (observers concluded that it was designed to impact the lunar body but instead passed it by, 3,725 miles (5,995km) above its surface) in 1959.

Conversely, if Chandrayaan-3 touches down as planned, it "would be the first time for India to actually succeed", in achieving a "soft landing" on the Moon, says Paladini, noting how the nation's previous attempt, with the Chandrayaan-2 lander, ended in failure when the vehicle crashed onto the lunar surface in September 2019. (India has technically sent a spacecraft to the Moon's South Pole before with its Moon Impact Probe, which smashed into a ridge close to Shackleton Crater in November 2008, but it was far from being a soft landing and the spacecraft was never expected to survive the landing.)

You might also like:

What is new here is the targeted landing sites at the South Pole of the Moon. No spacecraft has ever touched down there successfully. All of the Apollo missions went to locations further north, near to the Moon's equator – those landing sites featured relatively smooth terrain and plenty of sunlight. At the South Pole, in contrast, the terrain is much bumper, littered with craters, and light from the Sun arrives at a harsher angle. (Read about how the boots worn by the next astronauts to walk on the Moon will cope with the conditions at the lunar South Pole.)

Getty Images

Getty Images"The sun is very low over the horizon," explains Jack Burns, a professor of astrophysics and planetary science at the University of Colorado Boulder. "The shadows are very long, the Moon is very uniform in terms of its grey surface, so being able to differentiate between craters and boulders is going to be much more challenging."

The US aims to send a crewed mission, Artemis III, to the lunar South Pole as early as 2025, so learning from the experiences of robotic landers before that date will presumably be useful to some extent. But crewed spaceflight will always be much harder than uncrewed, notes Whitman Cobb. "I don't even see it as being necessarily in the same league," she says.

What really matters, going forward, is who is able to set up a sustained and worthwhile presence on the moon, argues Vishnu Reddy, professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona. He disapproves of talk of a race or competition between nations and private companies. "Honestly, I think it's a distraction," he says. "Competitions only take you to the flag. You can't have sustainable, long-term presence based on politics or trying to beat one nation or the other."

The scientific equipment aboard each lander is relatively similar, he points out. The vehicles will hopefully help scientists to better understand more about the crucial lunar water ice, minerals, and the Moon's limited atmosphere, among other things. Just getting a clearer picture of the lunar South Pole is helpful, as is proving the capacity to land safely in such a tricky location.

There is another way of framing current expeditions to the Moon, though, says Anu Ojha, engagement, international and inspiration director at the UK Space Agency, who was previously involved in reviewing the Luna-25 mission before the invasion of Ukraine led the European Space Agency to discontinue its activities with Russia. Think of it like international "architectures" competing against one another, he suggests. The US, UK and India are among 27 countries signed up to the Artemis Accords. Meanwhile, Russia and China are collaborating on their own future Moon base, the International Lunar Research Station. Construction could begin as early as 2026. Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 are essentially early forays from each of these two international conglomerations.

Alamy

AlamyAnd the question that hovers over the lunar horizon is this: what next? What if we do set up lunar bases and begin extracting resources from the Moon for use in future space missions? The Outer Space Treaty, signed in 1967, establishes the fact that no nation can own the Moon. However, a subsequent treaty, known as the Moon Agreement, which more carefully defines that no nation can own resources on the Moon, has never been signed by key countries including the US, China and Russia.

"What does that mean going forward, when you're mining resources? Does everybody have an equal claim?" asks Burns, pondering the political headaches that will likely face new lunar pioneers. These headaches are going to have to be sorted out somehow, he notes. "We don't want to end up in some territorial disputes on the Moon, things are bad enough on Earth."

For now, Luna-25 and Chandrayaan-3 fly silently through the vacuum of space, just small players in a human quest to explore the Moon and potentially expand the reach of our species into the vast Solar System beyond. These two landers are but tiny chess pieces on one very big board. But, as players of chess know, it is a game where every move counts.

--