What will the next footprints on the Moon look like?

Nasa

NasaThe moonboots worn by astronauts on the Artemis missions will need to protect their wearers from difficult terrain and extreme temperatures, but their most memorable role will be the prints they leave behind.

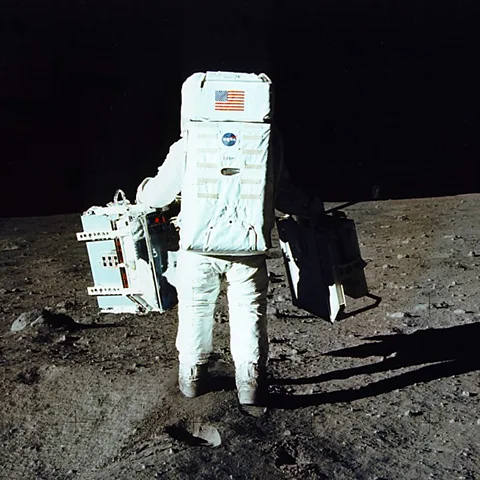

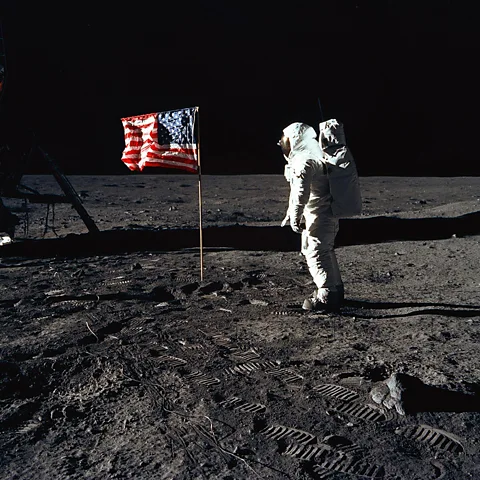

It is one of the most enduring images of the Apollo space era – a lone, shallow lozenge pressed into the grey, dusty soil of the lunar surface. Bars of compacted regolith streak horizontally across, formed by the grips on the sole of astronaut Buzz Aldrin's boot. Now unmistakable as one of the first footprints a human has ever left on another world, it is a potent symbol of human endeavour.

In reality, the print is just one of hundreds left by the 12 astronauts who set foot on the Moon between 1969 and 1972.

And, as far as we know, those prints are still there to this day. Without wind or rain to erode them away, they will remain on the surface for millions of years.

As Nasa now prepares to send a new crop of astronauts to the Moon's South Pole, there could be another set of footprints making their indelible mark on the lunar surface. But what will the first footprints on the lunar surface in 50 years look like? And how different will the boots that create them be from those worn by the original Apollo astronauts?

Nasa and its commercial partners have spent years designing and finessing the materials for the next generation of moonboots. When the four new astronauts finally land on the Moon in 2025 with the Artemis Programme, their footwear will need to perform in ways the Apollo boots never had to in order to keep their wearers comfortable and safe. They will need to protect the astronauts for extended periods in temperatures as low as -225 (-373°F), as well as keeping them steady on the heavily cratered terrain of the lunar South Pole.

Alongside incorporating innovative materials and technologies into the boots, engineers are also turning their attention to the prints that will mark the surface of the Moon for millenia to come. The soles of these lunar shoes will not only need to give adequate grip on the surface of the Moon, but they will be as iconic and instantly recognisable as those left by the first moonwalkers.

"There's definitely some functional characteristics that have to be built into it," says Zach Fester, a space suit engineer at the Nasa Johnson Space Center who has been leading the research and development on the new moonboot. "Traction is absolutely important – you're exposing the boot sole to a variety of surface features, so it needs good grip on harder rock and the fluffy regolith but also on harder metal surface such as vehicles, ladders and rovers. The tread also has to be robust against wear and tear. But aesthetics are certainly part of it too, because those pictures [of the footprints] are pretty iconic."

Nasa

NasaThe overall design of the spacesuits that will be used in the Artemis missions has been contracted to Axiom Space, a commercial space company that earlier this year conducted its second all-private astronaut mission to the International Space Station. A key part of the new spacesuits, which were revealed in March 2023, will be the moonboot itself. However, the exact design for the boots has yet to be made public. (Find out more about what it takes to make a suit fit for the Moon.)

But research published by Nasa about the requirements the boots will need to fulfil, together with early tests on some of the designs put forward, offer some clues.

Perhaps the biggest challenge will be the temperatures the astronauts will face compared to the Apollo missions, which were mainly conducted in relatively flat landing areas in the equatorial regions of the Moon. When Artemis III lands on the Moon, its crew will be touching down in a very different environment in the lunar South Pole.

"For the South Pole, we're looking at much colder temperatures," says Fester.

The region is known to have areas that remain permanently in shadow. "They haven't seen the sun for thousands of years," Fester says. "Some of them can get down to 48 degrees Kelvin (-373F/-225C ) or lower. If you are in the Sun, it can get north of 150F (65C). And a spacewalk can be anything from four to eight hours, so in that time you can encounter pretty large swings in temperature."

This means insulation is going to be key. Both Nasa and Axiom have been testing new types of insulating foams and coatings to help keep the temperature inside the boot comfortable.

"The boot is specifically designed to withstand the temperature extremes of the lunar South Pole, using advanced materials that didn't exist during Apollo," says Russell Ralston, extravehicular activity (EVA) deputy program manager at Axiom Space, which has called its moonboot the AxEMU. "We are using several unique materials to withstand the cold temperatures at the lunar South Pole. This includes novel formulations of fluoropolymers, insulation materials, and coatings designed to thermally protect the astronaut’s feet."

One option Nasa's engineers have considered was to add "active heating" elements into the boots to provide additional warmth. But the bootie radiators come with a trade-off, says Fester. "If you are actively heating you need to draw power from somewhere." This would mean batteries and cabling that could add weight to the boots and the overall load carried by the astronauts.

With astronauts due to explore the lunar surface for extended periods of time, and potentially constructing a permanent base on the moon in future missions, even small amounts of extra bulk could make moving around less efficient. The engineers will have to ensure the fit of the boots is as perfect as it can be, but face other challenges their counterparts in Apollo did not – the range of body sizes of the astronauts. Artemis will see the first woman set foot on the Moon. This will mean a far great range of sizes may be required for the boot than in the Apollo missions, where the astronauts were all male and were almost all the same height, age and weight.

"We are looking at ways we can work with the individuals to get a boot that's just right for them," says Fester, who spends many hours walking around in prototype boots and suits to test how they feel. But rather than make numerous custom sizes, the boots will come in select sizes that can then be fine-tuned with padding inserts and external tightening mechanisms.

"The AxEMU lunar boot will be much more comfortable and mobile than those used during the Apollo missions," adds Ralston.

The astronauts will also spend a considerable amount of time before they launch training in their boots to ensure they perform as expected on the Moon. "They are going to train and train in those boots, try different options, until they get the perfect fit," says Fester. "Breaking in moonboots is just as important as breaking in a new pair of shoes."

And for those who like an extra bit of comfort, there are always lower tech solutions. "I personally wear two socks on each foot – it feels way better over six hours," says Fester.

Nasa

NasaAnother major consideration comes from the lunar surface itself. The fine dust that covers much of the Moon is irregularly shaped and sharp, making it highly abrasive. It also carries an electrical charge that makes the dust stick to surfaces easily but can also play havoc with electrical equipment. Tracking this material back into a landing module or lunar habitat is definitely undesirable.

Ralston says the boots his company are designing will have an almost seamless design to minimise areas where dust could be trapped and they will use materials that can prevent the electrically charged dust from adhering to the boots.

But what about the footprints they will leave?

During Apollo, the astronauts wore stiff overboots that they strapped on top of a softer inner shoe that was part of the spacesuit itself. It was these overboots that gave the distinctive pill-shaped print on the lunar surface. And when they returned to the lunar capsule, the astronauts removed the overboots and left them on the Moon.

"The overboot was put on specifically for surface operations and then they tossed them afterwards – leaving them on the surface to save on mass when they came back home," says Fester. (Read more about the other strange objects left on the Moon.)

Fester and Ralston both say it has yet to be decided if the Artemis lunar boots will adopt a similar approach by using an overboot, but say it will be driven by the requirements for temperature and abrasion resistance. Early prototypes tested by Nasa seem to indicate this might be the preferred option. And the soles themselves appear quite different to those used during Apollo. One silicon outsole featured chevron shapes, while another had complex treads more like a hiking shoe to give better grip in the cratered surface of the South Pole.

Axiom Space

Axiom SpaceAlthough Ralston is keeping the details of what the final tread might look like under-wraps for now, he did offer one clue: "We have plans for a specific tread design that may incorporate a logo or other imagery that symbolise the significance of the return to the Moon."

Exactly what that might look like, however, he isn't saying.

One thing is clear – the next footprints on the Moon will be just as significant as the last, marking a new era in space exploration. Rather than simply being a destination in itself, the Moon is set to be a staging post for further manned exploration of the Solar System including Mars.

When asked what it feels like to be working on something that will leave an iconic mark on another world for possibly millions of years, Fester admits to some nerves.

"No pressure, right?" he says. "There's absolutely a strong sense of responsibility that comes with that. To me that picture represents a lot more than just a footprint left behind – it represents all the testing that happens on the ground, the rockets, the crew capsules, and the landers that get us to the surface. It's an image of what we can do together and how successful we really can be."

--