Should 'three-person babies' have the right to know their donors?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA growing number of children have been born with the help of a pioneering technique that effectively means they carry genetic material from three people. It is opening up a new debate on what rights they should have.

A groundbreaking fertility procedure that uses DNA from three people to prevent devastating mitochondrial diseases has resulted in the birth of several healthy babies in a number of countries around the world – including, most recently, in the UK.

The new technique, called mitochondrial replacement therapy, gives hope to couples who have lost children to rare genetic conditions. But it has also faced opposition, partly because of broader concerns around processes that involve genetic modifications in humans.

With some of the first children to be born using mitochondrial donation turning seven years old this year, and the technique becoming more widely used, regulators and parents are also facing ethical questions to do with the children's identity and origin.

One crucial question being raised is whether the children should have the right to know their mitochondrial donors' identity.

Experts say that existing research on more established forms of donor-assisted conception, such as sperm and egg donation could help answer those questions – and find the best way to ensure the children's emotional wellbeing.

Alamy

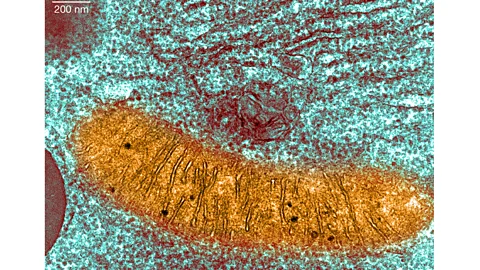

AlamyMitochondria are special compartments inside our cells that convert the energy found in food into a form that can be used to power bodies. But they can't do this if they carry faults that lead to disease. We inherit our mitochondria from our mothers, so a woman who carries some faulty mitochondria can pass these onto her children.

Mitochondrial replacement therapy is a form of IVF that combines the DNA from a mother and father inside an egg donated by another woman that contains healthy mitochondria.

The resulting embryo carries DNA from the two parents, but also carries a tiny amount of genetic material from the donor – around 0.1%. This donor DNA is contained within the mitochondria itself. Experts emphasise that the baby should not be regarded as a "three-parent" baby, but a "three-person" baby: they have two parents, and a donor.

Around the world, rules around the procedure are still evolving. The UK has pioneered laws and regulations to allow mitochondrial replacement techniques, and remains one of the few countries to have explicitly legalised it. Australia also legalised the procedure in 2022.

In the United States, the procedure is de facto banned: clinical research using mitochondrial replacement techniques in humans cannot legally proceed after the Food and Drug Administration expressed safety concerns. In Canada, the procedure is also banned. However, people have found ways to circumvent such restrictions by involving countries with laxer or absent rules. In 2016 a boy was born to a Jordanian couple in the US with the help of a mitochondrial replacement procedure, part of which was carried out in Mexico.

Unlike the parents' DNA, the donor's mitochondrial DNA does not influence traits such as hair or eye colour, or personality. This difference, and the fact that only a tiny bit of genetic material is from the mitochondrial donor, has had important regulatory consequences.

In the UK, a woman who donates her eggs for use in mitochondrial donation treatment is not considered the genetic parent of the resulting child, and remains anonymous – and the resulting child cannot apply to find out her identity. From the age of 16, a child can, however, access some non-identifying information about their mitochondrial donor, such as information about their personal and family medical history.

Sperm and egg donation, in contrast, is now open-identity only in the UK (the child can apply to know the donor's identity when they are 18).

John Appleby, a lecturer in medical ethics at Lancaster University, in the UK, disagrees with the UK's regulatory decision to make mitochondrial donation legally anonymous. He argues that children conceived via mitochondrial donation should have the right to find out the donor's identity, as they do in the UK in the case of sperm and egg donation.

"The psychological evidence to date indicates that some people conceived with donated eggs, sperm or embryos, feel it is important to know identifying information about their donors," he says. "They tend to express a number of reasons why, ranging from wanting to thank the donor, wanting to find other siblings, or because it matters that they have any genetic tie to their donor and possibly want to meet them."

In his view, many of those interests would also potentially apply to mitochondrial donation, which, after all, uses part of the eggs from a donor. In particular, there may be reasons that are not just about the genetic connection, and the quantity of genes passed on. "Based on what we know about people's motivations for wanting to contact their donor, the fact that a mitochondrial donor gave someone a life free of a terrible disease is likely a good reason for the donor-conceived person to want to contact them."

You might also be interested in:

Decades of research on new forms of families suggests that children are far more flexible about issues like their biological origins and genetic-relatedness than was previously thought. Open communication with the child about their origins, and being donor-conceived, has also been shown to be very important for their wellbeing.

A longitudinal study by the University of Cambridge Centre for Family Research followed up children born through egg donation from infancy to adulthood. It investigated a range of questions about their wellbeing, identity and relationships, such as how they felt when they learned about their biological origins and the quality of their relationship with their mothers (who used donated eggs to have them). Findings from the most recent phase of the study, published in 2023 and based on research done when the young people reached the age of 20 showed that they had good relationships with their parents and high levels of psychological wellbeing.

Susan Golombok, professor emerita of family research and former director of the Centre for Family Research at the University of Cambridge, who led the study, says she would expect similar findings among children born after mitochondrial donation.

"As 50% of the children's genes were from an egg donor, whereas only mitochondrial DNA comes from the egg donor in children born through mitochondrial donation, it is not expected that the children would experience psychological difficulties as a result of their method of conception," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn important finding from the study is that children born through egg donation benefit from being told about their donor conception when they are young, says Golombok. "Although the psychological implications of mitochondrial donation [might] appear to be less significant, it seems likely that these children also would benefit from openness about their conception," she adds.

Research on families created with the help of sperm donation sheds further light on the benefits of openness, and may help when it comes to envisaging how a three-person IVF baby may one day feel about their donor.

"I think it's terrific that parents who would ordinarily lose a child to mitochondrial disease now have a potential option for giving birth to a healthy child," says Nanette Gartrell, a psychiatrist and principal investigator at the National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study in the US. The study, which began in the 1980s, has followed a group of lesbian mothers who conceived children via sperm donation, and also followed the children's development and wellbeing into adulthood. Gartrell says the study's findings hold important wider lessons, for example when it comes to the issue of openness versus secrecy around donor conception.

"Children conceived by sexual minority parents through assisted reproductive technology know about their conception from early childhood," says Gartrell. The mothers in the study, for example, were always open with their children about their origins. As adults, roughly half of the donor-conceived children in the study reported good relationships with their donors, while 20% wished for more contact.

Interestingly, those who had a positive relationship tended to highlight factors other than their genetic connection, such as the donor's kind personality, or the fact that they talked to each other a lot. Some participants said that looking for a resemblance was part of why they had wanted to meet their donor, while others reported a more general curiosity. One participant wrote that before meeting his donor, he felt "the mystique of unknown origins".

Based on her research and wider knowledge of the impact of secrecy versus openness on children conceived via sperm donation, Gartrell argues that openness and the opportunity to contact the donor at an age-appropriate time are more beneficial for the children than concealing it. "Human beings have a right to know their genetic origins to the extent possible," she says.

In the case of mitochondrial donation, there may also be other reasons why the child may wish to know, according to Gartrell. "Informing children of the mitochondrial donation that prevented a fatal disease is also important because this information may prove medically helpful to those children in ways that scientists are currently unaware. As a psychiatrist and researcher, I would consider this disclosure similar to informing a child that a life-saving foetal cardiac procedure was performed on them, for example."

For now, the pioneering procedure of mitochondrial donation treatment may feel like we're treading completely new ground – creating an entirely new kind of human, in a way. But as these studies on other reproductive technologies suggest, the children themselves may be far less fazed by their origins than the public. Whether and how soon the public will embrace the technique may, however, continue to vary from country to country – just as societies still show varying attitudes to standard IVF.

--