How assassins revealed a hidden side to Queen Victoria

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring her long reign, Queen Victoria faced seven threats to her life from men who had decided to kill her. Outwardly stoic in the face of these incidents, her personal diaries reveal a different story of the toll they took on her mental state.

On 27 June 1850, Queen Victoria had a brush with death. That evening, she took three of her children to visit her ailing uncle in his mansion on Piccadilly. Outside, hundreds of excited Londoners gathered and waited for her to emerge.

Most onlookers only wanted to catch a glimpse of the monarch, but one man had a different goal. Just as the royal party left, Robert Pate pushed to the front of the crowd, ran towards the Queen's open-topped carriage, and struck her on the head with a metal-tipped cane. The crowd erupted in panic. Amidst the chaos Victoria is said to have stood, adjusted her bonnet, and calmly announced, "I am not hurt".

Bob Nicholson is a reader in history at Edge Hill University and the host of the podcast series Killing Victoria. Find out more about the men who tried to kill the Queen by listening to the podcast on BBC Sounds in the UK or as a Podcast in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

This was the fifth time that she had been attacked since her 1837 ascension to the throne. Media accounts often emphasised her coolness. The Morning Post reported that "her Majesty betrayed no feeling of alarm" and had the "complete self-possession" to courteously acknowledge groups of cheering spectators as her carriage made its way back to Buckingham Palace.

This description of the Queen as resilient, unflappable, and committed to duty chimes with her popular image, both then and now. Victoria's famous quote – "we are not amused" – may never have passed her lips, but it has come to symbolise the sangfroid of the Queen and the mood of an era. Many people imagine the 19th Century as a time of repressed emotions, while others celebrate its supposed stoicism. (Read more about the origins of the "stiff upper lip".)

Despite her public façade, Victoria's personal journals reveal an emotional side. Looking back on the attack from the safety of Buckingham Palace, she wrote that it now seemed "like a horrid dream". As her account of the incident unfolded, fear and confusion gave way to anger, and she came to see the "outrage" as "the most disgraceful and cowardly thing that has ever been done". Victoria wasn't the only one to feel some emotion. Prince Albert was "dreadfully shocked", while Sir George Grey, the home secretary at the time, arrived at Buckingham Palace "greatly distressed & in tears". In the hours after the attack, Victoria was still "shaken, nervous, & unable to eat".

Still, she ventured to the opera where joyful crowds threw their hats in the air and serenaded her with spontaneous renditions of "God Save The Queen". While not all Victorians were enthusiastic monarchists, attacks on the Queen prompted these outpourings of emotion. As Victoria herself quipped, "it is worth being shot at to learn how much one is loved".

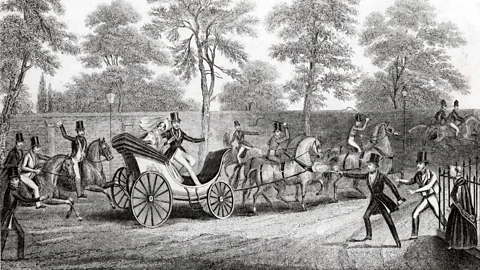

Her determination not to hide away in the wake of the attacks was typical of Victoria in her younger years. Back in 1842, a teenage boy named John Francis had pointed a pistol at her carriage as it drove up Constitution Hill. Albert spotted him, but Francis didn't fire and managed to slip away. Knowing that a potential assassin was on the loose, Prime Minster Robert Peel urged the Queen to stay at home while his new police force hunted the attacker. Victoria refused. The next evening, she and Albert rode out in their open-top carriage flanked by guards but still exposed. Sure enough, Francis made another attempt, this time managing to fire his pistol at the royal couple moments before being seized by a policeman. Victoria emerged unhurt, but it could have ended very differently.

Alamy

AlamyFollowing Francis' assault, the Queen immediately resumed her royal duties and continued to appear in public, seemingly unscathed. This was a defiant and public display of courage by the Queen, and the press lauded her bravery. A poem in The Times described her as a "lion-hearted monarch" and dubbed her "A King in courage, though by sex a Queen". It was important for Victoria to project this strength in public. Some Victorians – including one of her subsequent attackers – bristled at the idea of living under "petticoat government" and believed that women lacked the grit and composure to rule.

But traumatic experiences like this can be difficult to shake off. Four different men shot at Victoria in the 1840s. By the time Robert Pate attacked her in 1850, she had begun to feel anxious in crowds – a not uncommon outcome of a traumatic event like being a victim of a violent crime. In her journal, she confessed that when the public pressed close to her carriage it "always makes me think more than usually of the possibility of an attempt being made on me".

In the end, however, the most devasting emotional blows didn't come from assassins, but from the deaths of people she loved. A few days after Pate's attack, Robert Peel – a staunch ally of the Queen and friend of Albert – died after falling from his horse. Victoria's uncle passed away shortly after. In her journals, she confessed to being "overcome with a feeling of awe & sorrow".

This, of course, was nothing compared to the intense grief she experienced when Albert died in 1861. For the following decade, she withdrew from public life and sank into a deep depression. She later described it as a "violent grief" during which her "nightly longing to die" never left her. She lived for another 40 years, but never fully recovered. She was eventually coaxed back into making occasional public appearances – two of which drew out yet more assassination attempts – but never with the same regularity or relish as in her youth. The final year of her life was marked by more loss, as well as chronic pain and disability, and her journal entries suggest another depressive episode.

Victoria survived the seven attempts on her life, gave birth to nine children, and found a way to "endure", as she put it, after losing Albert. While her wealth and power insulated her from many of the trials that less fortunate Victorians faced, she still felt the impact of personal grief. Her public displays of bravery and self-control tell only half her story.

* The seven attacks on the Queen are explored in the seven part podcast series Killing Victoria, out now on BBC Sounds in the UK and as a Podcast in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Each episode traces the lives of the assassins and considers the impact that their actions had on the Queen.

--