The lost medieval sword fighting tricks no one can decode

Alamy

AlamyNo one knows how medieval knights really fought.

One day, in the mid-12th Century, an unremarkable monk sat down in St Edmund's Abbey, Suffolk, and set pen to parchment. He was chronicling the scandalous life of a man he had met some years earlier – the story, he hoped, was not too improper.

The anonymous monk's interest had begun at another abbey, in Reading, where he had been visiting. Within the imposing building's rough flint walls, in the shadows of a virtually unlit room, he met the resident brothers. Among them was one who immediately stuck out as unusual – a monk who, though now dressed in the same hooded robes as the rest, had once led a very different life. In hushed tones, this man explained how he had become a monk by accident.

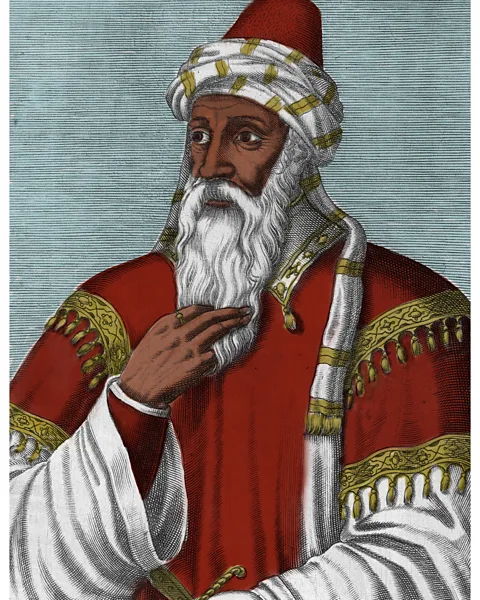

In 1157, Henry of Essex had been noble – by birth, rather than deed – wealthy, and powerful. He was a knight famous for his skill with a sword, and trusted by Henry II of England. He also wasn't very nice – he stole money, brought shame on women, and had an innocent man tortured.

Then a bizarre incident at a battle in Wales threatened everything. Essex mistakenly announced that the king was dead, almost causing the army to give up and flee. Six years later, in Reading, one of his own relatives publicly declared that this had been treason and challenged him to a duel. This would be a trial by combat.

With crowds watching from the muddy banks of the River Thames, the accusing relative – also a knight – attacked with "hard and frequent blows". At first, Essex defended himself with skill, but after a series of visions of those he had wronged, he was filled with shame and fear. He flew at his opponent blindly, abandoning everything he had ever learned. Amid much clattering of blades on armour, he fell.

The king ordered the local monks to carry Essex's body away and bury it. Miraculously, Essex survived, and lived the rest of his life in penitence among them – where many years later, he met the unremarkable chronicler. It was written as a moral tale, but there's another perspective: Essex had abandoned his sword-fighting knowledge, and lost everything.

Alamy

AlamyKnights were the biggest celebrities of the medieval era. The best among them were rewarded for their skill with castles, lands, and courtly influence. They were widely celebrated as the romantic heroes of their age – livening up legends, poems and paintings with their clashing blades and chivalrous deeds.

Of course, becoming a knight required more than just shining armour and a noble steed – they needed technique. It was normal for ambitious warriors to train for up to a decade, often from childhood, practicing nimble footwork, how to deflect attacks, and various gruesome ways to kill opponents as quickly as possible.

Sword fighting was not a matter of random slashing or prodding – it was a sophisticated martial art to rival kung fu or sumo wrestling. But centuries later, crucial information needed to understand its secrets has been lost. Despite years of studying them, to this day the techniques involved remain mysterious.

In fact, the elaborate back-and-forth swordplay in every film, series, or play of the period has been largely made-up. "It does suck the enjoyment out of watching TV sometimes," says Jamie MacIver, a longsword instructor and the former chairman of the London Historical Fencing Club, "because you look at it and you think, 'Oh my God, wait, what are you doing?'."

How has this happened? And will we ever work out how it was really done?

Heroes and butchers

The ultimate experts in medieval sword fighting were the "fight masters" – elite athletes who trained their disciples in the subtle arts of close combat. The most highly renowned were almost as famous as the knights they trained, and many of the techniques they used were ancient, dating back hundreds of years in a continuous tradition.

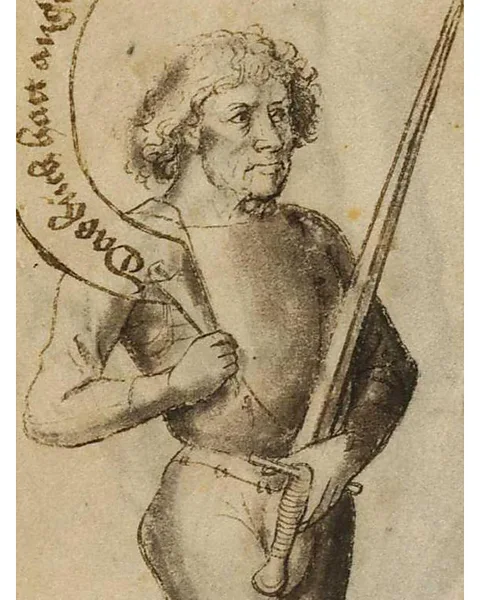

Little is known about these rare talents, but the scraps of information that have survived are full of intrigue. Hans Talhoffer, a German fencing master with curly hair, impressive sideburns and a penchant for tight body suits, had a particularly chequered past. In 1434, he was accused of murdering a man and admitted abducting him in the Austrian city of Salzburg.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

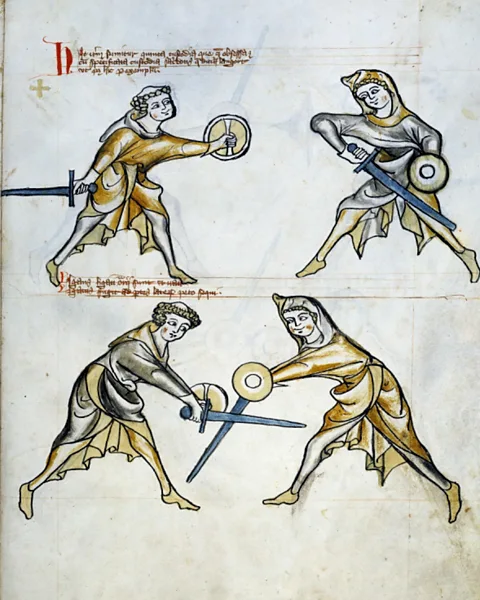

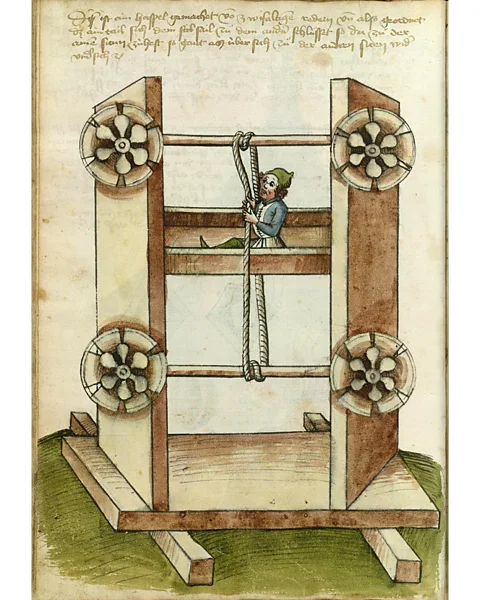

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkFight masters worked with a grisly assortment of deadly weapons. The majority of training was dedicated to fencing with the longsword, or the sword and buckler (a style of combat involving holding a sword in one hand, and a small shield in the other). However, they also taught how to wield daggers, poleaxes, shields, and even how to fight with nothing at all, or just a bag of rocks (more on this later).

It's thought that some fight masters were organised into brotherhoods, such as the Fellowship of Liechtenauer – a society of around 18 men who trained under the shadowy grandmaster Johannes Lichtenauer in the 15th Century. Though details about the almost-legendary figure himself have remained elusive, it's thought he led an itinerant life, travelling across borders to train a handful of select proteges and learn new fencing secrets.

Other fight masters stayed closer to home – hired by dukes, archbishops and other assorted nobles to train themselves and their guards. A number even set up their own "fight schools", where they gathered less wealthy students for regular weekly sessions.

Neil Grant, a trustee of the Royal Armouries in the UK, explains that one such teacher set up a programme at the University of Bologna in northern Italy, where records show that attendance cost about the same as a modern gym membership. There he taught aspiring warriors, knights, and ordinary citizens – preparing them for war or mentoring them to survive judicial duels or tournaments.

It was no game. In the Middle Ages, apprentice fighters had the highly motivating prospect of not dying as a reward for their efforts, but there was also social honour to be gained – the very best fighters were able to transcend the hierarchies of the day, catapulting themselves into the ruling classes.

At the very least, sophisticated swordplay was essential so as not to waste money. "To make even a small sword would take an incredible amount of steel," says Richard Scott Nokes, an associate professor of medieval literature at Troy University in Alabama, US, who explains that it would also have taken hundreds of kilograms of charcoal to get it hot enough. "The sheer cost meant that you didn't just have a weapon and say, 'Well, I'll just go out there and stick them at the pointy end'," he says. "You didn't want to damage it."

Alamy

AlamySome fight masters regarded their techniques as top secret, though exactly how classified they actually were is up for debate. One particularly famous 14th Century Italian knight, Fiore de'I Liberi, vowed to keep his craft under wraps so that his students could have an advantage – otherwise anyone could have learned how to fight against them.

However, as Grant points out, this may have been more about marketing than integrity: "If you've got three fight masters and one of them is going 'I'll teach you the stuff everybody knows' and the others are going, 'No, I have mystic arts that no one else could possibly counter', which one are you going to go with?"

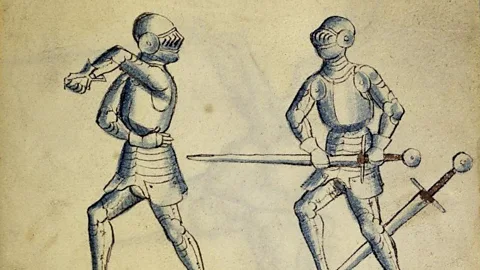

Fortunately, a number of knights had the opposite idea, writing their tricks up in "fight books". These ornately decorated manuscripts included descriptions of various techniques, often accompanied by illustrations – sometimes of real medieval people – demonstrating them in practice. The books would have been commissioned by the instructors' wealthiest employers and could take several authors working together years to complete.

For all their beauty, the hand-drawn works could also be decidedly bloodthirsty. In Talhoffer's 1467 manual, neat sequences of moves that look almost like dancing end abruptly with swords through eye-sockets, violent impalings, and casual instructions to beat the opponent to death. Some signature techniques even have names – chilling titles like the "wrath-hew", "crumpler", "twain hangings", "skuller" and "four openings".

Despite passing through countless generations of owners, and – in some cases – centuries of graffiti, burns, theft, and mysterious periods of vanishment from the historical record, a surprising number survive today. This includes at least 80 codexes from German-speaking regions alone.

Impossible moves and missing clues

But there's a problem. Many of the techniques in combat manuals, also known as "fechtbücher", are convoluted, vague, and cryptic. Despite the large corpus of remaining books, they often offer surprisingly little insight into what the fight master is trying to convey.

"It's famously difficult to take these static unmoving woodcut images, and determine the dynamic action of combat," says Scott Nokes, "This has been a topic of debate, research and experimentation for generations."

Alamy

AlamyOn some occasions these manuals seem to depict contortions of the body that are physically impossible, while those that attempt to convey moves in three dimensions sometimes give combatants extra arms and legs that were added in by accident. Others contain instructions that are frustratingly opaque – sometimes depicting actions that don't seem to work, or building upon enigmatic moves that have long-since been lost.

Oddly, the text is often written as poetry, rather than prose – and a few authors even made it hard to interpret their works on purpose.

Lichtenauer recorded his instructions in obscure verses which remain almost incomprehensible today – one expert has gone so far as to call them "gibberish". According to a contemporary fight master he trained, the grandmaster wrote in "secret words" to prevent them from being intelligible to anyone who didn't value his art highly enough.

Even when it is possible to decipher what a combat manual is describing or demonstrating , some experts suspect that crucial contextual information is always missing.

Take Philippo di Vadi, another Italian fencing master. He wrote his fight book in the 15th Century, and it's mostly text-based – again, written in poetry, some of which includes passages chosen purely because they rhyme. As one analysis points out, to get to any meaningful insights translators must wade through obscure metaphors that have long since vanished from common use, such as: "If you have salt on your brain [if you're gifted], You must consider here, The best way to climb these stairs [the best way to become successful]."

Even the parts that are genuinely instructive about a certain technique often lack critical details. "Most of the time it's not so much that you can't work out what's said, it's that there's four or five possibilities what it could be. And sometimes they don't make sense," says MacIver.

For MacIver, one of the hardest moves to grasp is di Vadi's footwork – where you step while "cutting", a kind of attack made with a chopping motion of the sword. "Throughout the text, he's like, 'Oh I've got new footwork, it's better than the ancestors' footwork'," says MacIver. "So he's really emphasising how important it is for him. And then he writes about it – and it's just incomprehensible."

Alamy

AlamyThen there's the images. At the time, it wasn't yet common to draw or paint in three dimensions. So while this emerging fashion in art was being finessed, attempts to convey depth in pictures could often be confusing – and this includes those in fight books. "Sometimes you can't actually work out which of the two fencers involved is supposed to be winning," says MacIver. "There's one in particular… both fencers have a sword against their neck."

To get to the bottom of what knights were really doing, all this needs to be untangled. But even when it is, there are countless other unknowns, such as exactly how often the most peculiar techniques were actually used.

"Some [fight books] bring in stuff that's so weird you're going 'this cannot be used with any frequency'," says Grant. He gives the example of a sequence of fight books known as The Gladiatoria Series, which contains some eyebrow-raising tips. "One of the moves involves unscrewing the pommel of your sword [the circular fitting by the handle] and throwing it at somebody," he says.

Where they're only mentioned in one book, it's hard to tell whether such outlandish tricks really were in common use, just neglected by most authors, or so rare they almost never happened.

More monks …and women

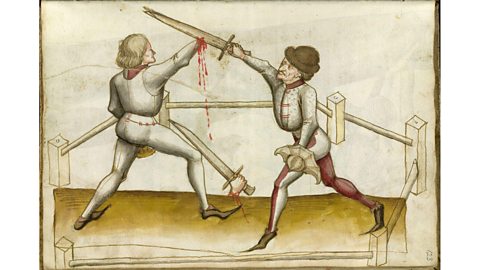

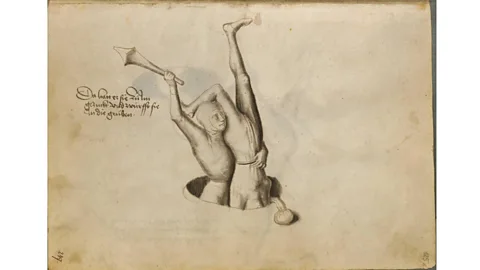

Tucked away in the back pages of Tahhoffer's book, past the endless images of medieval men disembowelling each other with swords, clubs, and poleaxes, is an arresting sight: a man stands waist-deep in a hole, looking rather anxious, while a woman in a loose-fitting bodysuit calmly swings a kind of improvised club through the air above him. In fact, she's wielding a 4 to 5lb (1.8-2.3kg) rock – roughly equivalent in weight to a standard modern brick – which has been wrapped in her veil. He is armed with a club of equivalent length.

The strange scene, which has baffled historians for decades, is thought to be a "judicial duel" – the same method used to try Henry of Essex for treason. In the medieval era, this was a perfectly legal way to settle disputes, and relied on the judgement of God. According to the logic of the age, there must be a guilty party – and naturally, the celestial power above would ensure that they lost.

Alamy

AlamyIt was normal to train for these fights exactly as you would for any other combat, and the images seem to be instructive. There are nine images in total, each depicting a different move. As usual, they're not particularly easy to follow, but in some, the man successfully kills the woman – in one particularly dramatic scenario, she's pulled into the hole head-first – while in others, she is the victor.

It's been widely speculated that this particular battle is an attempt to resolve a marital dispute, and possibly even "divorce by combat" – the unusual setup may have been contrived to remove some of the man's advantage. But as with many bizarre techniques in fight books, it's a total mystery.

"It's very, very odd – please do not ask me to explain it!" says Grant.

And this is not the only unexplained incidence of women in fight books. The oldest known European combat manual is a roughly 750-year-old book known as MS I.33 – the title page with its actual name and author is missing. This curious tome contains instructions for sequences with the sword and buckler, and involves a cast of characters that's still confounding historians today.

Alamy

AlamyFor a start, around half the scenes depict a priest – complete with the characteristic bald patch, or "tonsure" haircut, and robes – duelling with a scholar. This alone is highly unorthodox. Does this mean fencing was a common pastime at monasteries? Is it even possible that disgraced nobles like Essex may have continued honing their skills after enrolling as a monk? Or is the inclusion of the religious figures somehow symbolic? The book's earliest recorded home was, in fact, a monastery. But to this day, no one knows.

The rest of the images are just as odd – depicting a woman named Walpurga battling the priest. She wears her hair loose in waist-length braids, or dons the traditional headdress popular with women at the time.

Why did sword fighting disappear?

Though knights had their heyday in the medieval era, sword fighting remained an important part of European culture for centuries. By Tudor times, it was more popular than ever.

Previously, fight schools had been common in German towns, but banned in England – they were seen as a threat to law and order. Then the rules began to loosen up. "If anything, you start getting the rise of civilian duelling. For most of the Middle Ages, people don't walk around with swords all day any more than modern people walk around with assault rifles on their shoulders," says Grant. Then in the 16th Century, this became perfectly acceptable – even fashionable. "We start getting duels over increasingly silly points of honour," he says.

By this time, many of the ancient sword fighting techniques were already being abandoned, and the practice was starting to evolve into modern fencing. One contemporary historian was particularly scathing about the decline of the old ways, including the recent preference for the rapier over traditional short swords – although "he is also the kind of guy who [if he were alive today] would rant on YouTube about things," suggests Grant.

The final blow came with the invention of pistols. In the 18th Century, these new weapons eventually replaced swords as the preferred method of duelling – while you had to learn how to wield a sword, anyone could simply pull a trigger.

It wouldn't be completely unprecedented for a woman to fight in the Middle Ages. In Europe, Joan of Arc, a peasant from northeast France, famously donned armour to participate in the Hundred Years' War, and Margaret of Anjou, an English queen in the 15th Century led her own army into battle. However, it's not thought that women were routinely allowed to fight, so the casual way Walpurgia is included is striking. "People have come up with all sorts of theories. but we just don't know," says Grant.

Padded jackets and blunted swords

Surprisingly, the people trying to figure this out are often not historians, but modern martial artists.

Over the last 20 years, interest in Historical European Martial Arts (Hema) has been steadily growing, and today there is a thriving community of amateur enthusiasts who spend much of their free time poring over fight books – often translating them from ancient European languages such as Middle High German themselves.

These raw conversions still need some interpreting, so to go any further the martial artists talk them through and come up with some possible moves that could fit them. And this is where it gets serious. "Really, the only way of getting to some kind of answer is to try them out with your friends," says MacIver.

The goals of modern enthusiasts and medieval fight masters are not well-aligned – the former strives to avoid injuries at all costs, while the latter wanted to teach how to murder an opponent as quickly as possible. So, nothing happens without comprehensive protective equipment – thick jackets with foam inserts around the vital organs, protective gloves and trousers, and a heavy-duty fencing mask.

Then the move is performed at a glacial speed, to work out the mechanics. Instead of real swords, they use blunted ones of a similar weight. "And they're more flexible. So if you thrust at a person it doesn't just push into them," says MacIver.

Eventually, after several attempts with different methods, the martial artists might settle on the one that most closely matches the images and captions. Finally, it's performed at a normal speed, usually as part of a sequence with other ancient techniques.

If they're successful, the reward is almost a form of time-travel – interacting with fight masters who died hundreds of years ago, and experiencing long-forgotten physical actions. Who knows, perhaps the same swish of a sword is what felled Henry of Essex?

"It is very satisfying, when you're finally in a [Hema] tournament, and you do something that you can trace back to a book that was written 500 years ago," says MacIver.

Alamy

AlamyBut the process can be extremely convoluted – often fraught with confusion and giant leaps of guesswork. "It's a lot of back and forth, you know, you go down blind alleys all the time," says MacIver, "So you'll think, 'okay, I think I've got it', and you try something and you're like, 'this doesn't work at all.'"

In the quest to solve di Vadi's famous fancy footwork, MacIver came up with four possible moves that broadly fit the ambiguous poetry laid down for his instruction. "And they all seem to work fine," says MacIver, "so it's almost impossible to work out which one he meant… I have a friend who speculated that maybe he meant all four, but I think that might be giving him too much credit."

In other cases, the clue they might be onto something is a sharp pain and a cry to stop. While attempting to simulate an arm-breaking move, MacIver and his friend discovered this was one to add to their blacklist. "We were trying all these different options – that doesn't seem right, or that doesn't do anything, that's no good…," he says. When they finally found a likely solution, there was a sudden yelp. "…after the barest pressure, he's like, 'No, no, no, stop, that's it.'"

Alamy

AlamyOf course, it's not always so easy to tell if a technique has worked as intended, and martial artists are continually updating their interpretations as new evidence emerges. Take di Vadi's "guards" – defensive postures that you adopt before beginning a sequence of sword fighting actions. MacIver explains that getting these starting points right is essential, because everything that happens afterwards involves moving from one to another.

For about two years, he believed one was instructing him to hold his sword on the right side of his body – then one day, something clicked, and he realised it was the exact opposite. "It's very hard to tell from the image, because perspective isn't very good. It was kind of flat. And there are some kind of visual cues but they're not obvious like, how bent is the elbow, and a few other bits and pieces as well," says MacIver.

Even with the more obvious moves, some historians believe martial artists are attempting the impossible. In this view, attempting to recreate ancient fighting techniques is a bit like resurrecting long-lost music – both relied on intangible assumptions that were common knowledge at the time, but have long been forgotten.

As with medieval fighting, descriptions of the music at the time are frustratingly vague – long before it was expressed in notes, it was written up via "melodic outlines". Everything else you needed to interpret a particular song was stored in the musicians' brains, passed down faithfully through aural traditions. Once it had gone out of fashion, it stopped being transmitted – and as they died off, it vanished with them.

In fact, historians are increasingly recognising the importance of so-called "embodied knowledge" – where the body learns how to act through practise or observation – for understanding the past. This kind of sensory memory includes things like riding a bike, which can be described in words but not mastered without physically getting on a saddle.

Unfortunately, medieval sword fighting is riddled with opportunities to get these physical details wrong. There's the unknown strength with which blows were landed, the tempo different moves were performed at – including how long to linger in each position, which could have varied widely – the exact angles of the sword's blade as it slashed through the air. Like trying to teach someone how to become a professional ballerina while only communicating via email, what are the chances of performing all the moves correctly?

Alamy

AlamyThat's not to mention the drastic difference between how you would behave when in real mortal peril, versus during a highly choreographed session at an after-work hangout. MacIver points to a striking fact highlighted by de'l Liberi, who told his students "…for him that plays at sharp swords, on a single cover [attempt to block a strike] that fails, that blow gives him death.". Fighting without armour was so dangerous, the man himself only did it five times in his entire life – and never voluntarily.

In fact, many modern assumptions about how knights fought probably don't hold up. One is the elegance of sword fights, which were nothing like the depictions on television or even in medieval literature. In theory, knights were bound by the code of chivalry – a set of standards for how to behave fairly on the battlefield. And yet, according to Grant, these lofty ideals often weren't even honoured even in theory, let alone in practise.

"Certainly Fiore [de'l Liberi] knows what a fair fight looks like and he wants no part of it," says Grant. "The important thing is it's about making sure you're the one alive in the end. If that means pulling dirty tricks, 'Okay, great. Go for it.'"

In fact, there are hints that real-world combat would have been shockingly barbaric. Grant points to the insights provided by medieval skeletons, which show that fights rarely occurred on a blow-by-blow basis, at least in war – they were messy, rapid, and often involved several men attacking a single adversary simultaneously.

"What happens is you get a good strike into somebody's head and they go down under a flurry of blows," he says. "…very commonly what you'll see [on the skull] is they have six head wounds, of which two or three will probably be fatal. The second you're off balance, your opponent is going to follow up and they're going to be on top of you – they're going to keep hitting."

However, despite the large gaps between modern re-enactments and historical reality, MacIver is undeterred. He's optimistic that – irrespective of inevitable mistakes – the ancient fight masters would approve of what Hema enthusiasts are attempting. After all, some recorded their secrets exactly because they wanted to avoid them being lost.

As di Vadi explained 540 years ago, he wrote his own fight book so that the ancient techniques he learned "do not disappear through my negligence". Though it's very much a work in progress, you could say he's on track to achieving this goal.

*Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett

--