The tank that could fly into battle

Public Domain

Public DomainIn World War Two, the Soviet Union devised a tank that could fly into battle. What happened to this ingenious, if unorthodox, concept?

The rapid evolution of armoured warfare in the years after World War One changed the way wars would be fought.

The Western Front had quickly devolved into static lines of trenches, with thousands of men dying in attacks that might only lead to the gain of a few hundred yards of territory. Barbed wire, artillery and machine guns made frontal advances hugely costly. It was the advent of the first armoured tanks in 1917 which broke the deadlock – the tanks were able to drive through barbed wire and were largely impervious to machine gun fire.

Army tactics pivoted to a new form of warfare that mimicked the cavalry campaigns of old – huge battles undertaken at speed across vast swathes of land. Another more modern weapon – aircraft – broadened the scope even further. Military planners had to grapple with the idea of armoured advances that would cover tens of miles in a single day – a feat almost unthinkable a few decades before.

In the 1930s, several armies began to think of how troops isolated by the course of battle or dropped by parachute far beyond enemy lines could get armoured support quickly. Delivering small tanks via large bomber aircraft seemed to be the best way, and cautious experiments took place, notably in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. One concept was to sling small tankettes – a lightly armoured tank armed with machine guns – under the wings of a large bomber aircraft, which would land, unload the tanks and fly off again. This was technically feasible but had one major flaw – there would have to be enough flat land nearby for such a large aircraft to land.

Another idea was more outlandish – why land the plane when the tank could land itself? Enter the 'glider tank'.

You might also like:

Military use was a major reason for glider development in the first half of the 20th Century. Germany, the USSR, the UK and US poured much effort into gliders which could carry troops and cargo into battle. The gliders were towed behind transport aircraft – much as modern sports gliders are towed behind a light aircraft – and released near the target to continue towards the target. Though the gliders needed a clear landing space to be effective (which restricted where they could be used), they proved to be a decisive weapon in World War Two.

In the early 1930s, tanks became smaller as military planners gravitated towards more mobile warfare. American engineer J Walter Christie, who invented an innovative suspension system used in many World War Two tanks, first looked at the concept of a flying tank in the early 1930s. Christie's design was more ambitious than those that followed. It involved bolting a pair of biplane wings and a tail onto the tank, as well as a propeller powered by the tank's engines. According to Christie, the tank would be able to get airborne at little more than 100 yards (330ft) and then be able to carry on towards its landing ground under its own power.

Sergey Ryzhov/Getty Images

Sergey Ryzhov/Getty Images"What is more, the pilot of the flying tank does not need the level ground required by a bombing plane to take off," Christie was quoted in Popular Mechanics in 1932. "He can take off through mud, through bumpy ground, and ground which would prevent the average plane from rising."

The US military was less convinced than Christie, and the innovative idea was not taken up. But a few years later, another equally visionary designer in the USSR took the concept off the drawing board – and into the air.

Oleg Antonov had been fascinated with aviation from his childhood days. While still a teenager he designed a glider of his own. His talents for design eventually led him to a role as the chief designer in the Moscow Glider Factory, where he designed more than 30 different gliders.

Soviet military planners were beginning to understand that paratroop units might need heavier weapons to help them survive in isolated pockets, far from friendly forces. One option investigated was to drop small tanks from large bombers using large parachutes, but as Stuart Wheeler, a curator at the Bovington Tank Museum in the UK explains, this was not without problems.

"One of the things that we see with the Soviets in the post-war period is this idea of dispersal, dropping vehicles with multiple parachutes. But where were the crew? They also threw the crew out but they might land far away and have miles to travel to the vehicle.

Kaboldy/CC BY-SA 3.0

Kaboldy/CC BY-SA 3.0"The tankettes slung under a Tupolev is as solution to a problem, and not far away from what was happening in the US in the 1960s, with Sikorsky helicopters slinging vehicles underneath the aircraft." But in the 1930s, such ideas just weren't practical.

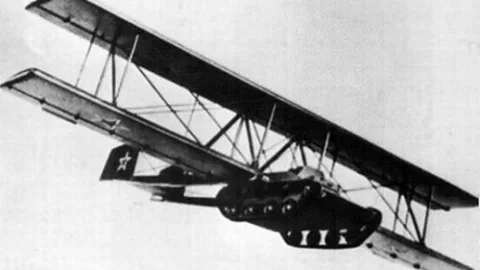

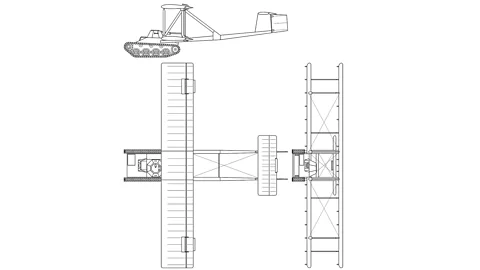

In 1940, just a year before the German invasion of the USSR, Antonov was brought in to work on a glider that could land small tanks. But Christie's design had intrigued him, and he worked instead on a flying tank design called the A-40. The prototype used a T-60 tank – a small, fast tank used for reconnaissance – on which were bolted a pair of biplane wings and a long tail boom. It was not an ideal compromise, says Wheeler. "The problem is the only vehicle they can actually get in there is a 1937 design which is hampered by its thin armour and its small gun." What worked in the gliding tank's favour was that it wouldn't expose large, slow carrying aircraft to ground fire – the tank would be released some way from the landing zone, and glide to a stop.

A scale model of the A-40 built a few years ago by a Dutch museum shows the sheer scale of this ingenious, if unorthodox vehicle (you can see it above). "The tank only weighs about six tons, and it's pretty small," aviation journalist Jim Winchester tells BBC Future. "But the wingspan is as long as a small bomber and it has twice the wing area." Two sets of wings stacked one above the other – are needed to generate enough lift to keep the tank aloft.

Antonov's design, however, stayed on the drawing board until long after Germany's invasion of the USSR in 1941. It's here that Antonov realised just how difficult it can be to get the idea from paper to reality. Only in 1942 was a prototype actually built. On 2 September 1942, test pilot (or in this case, test driver) Sergei Anokhin took the controls of the tank, connected to a Tupolev TB-3 bomber by a long tow rope. The A-40 was about to make its maiden flight.

"To test fly it, they have to leave the ammunition out and most of the fuel to save weight," says Winchester. "The concept was that as the tank's turret turned, you moved the controls on the wings. You just move the gun left or right." But the tank was so heavy that the turret had to be removed as well.

The Tupolev took off with the A-40 attached, but it had to ditch the tank early to avoid crashing – the drag created by the cumbersome vehicle proved too much. Anokhin managed to glide the tank to rest in a field. After landing, he was able to dismantle the wings and tail and then drive the tank back to base. The A-40's basic aerodynamics had proved to be sound, but the first – and it would turn out, only – flight showed the difficulties in getting such a heavy vehicle into the air.

"It's called a flying tank, but if you say that people will think of something scooting about and firing its gun, but that really wasn't the case," Winchester says. "In some ways it was a solution in search of a problem."

The Tank Museum, Bovington

The Tank Museum, BovingtonSoviet planners ultimately wanted the A-40 concept to be used with the much heavier and effective T-34 tank. But the botched maiden flight showed there was no aircraft powerful enough to get the glider off the ground – a fully-laden T-34, at 26 tons, was more than four times that of the diminutive T-60.

Such a small tank might have been useful as support for partisan units, who operated far behind the frontlines, but it would have proven less useful in a major battle. "You have a tank that might be useful in certain circumstances, but not in a properly contested environment," Winchester says.

Antonov's design never flew again, but it was not the end of the flying tank concept. Japan, which had also been interested in Christie's concept, also explored the idea during World War Two. Their Special Number 3 Light Tank Ku-Ro was an entirely new design built especially for the task. Like the A-40, it was intended to be towed behind a large aircraft, and released to glide its way on to the battlefield.

The designers found the stress of taking off at high speed would quickly shred the tank's tracks, so fitted a pair of skis. Like the wings and tails, the skis could be quickly dismantled after landing, and the small, 2.9-ton tank could go into action. But two years later the project was cancelled, as Japan found itself fighting a defensive war, and increasing US air superiority made it too dangerous to deploy such weapons from slow, vulnerable aircraft. The project never went beyond the prototype stage, and the tank itself never flew.

Britain too made some tentative moves towards a flying tank during the war, with a design that was simpler if no less outlandish – and it even flew. The Baynes Bat was a glider concept for exploring a larger design which could be used with a tank. Unlike the A-40, the Bat had one set of wings rather than two.

Public Domain

Public DomainIf the Bat had gone into production, it would have featured a particularly large wingspan– more than 100ft (30m) wide. The wing was also swept back, a common feature used in supersonic jet fighters introduced a decade later, but an aerodynamic leap forward rarely seen during the World War II. The Bat had no tail and instead had vertical stabiliser, much like tailfins, mounted on the end of each wing. The Baynes prototype did not actually feature a tank – the pilot sat in a tiny fuselage, dwarfed by the giant wing.

Its pilot, Robert Kronfeld, later remarked: "In spite of its unorthodox design the aircraft handles similarly to other light gliders with very light and responsive controls and is safe to be flown by service pilots in all normal attitudes of flight." But a few years later Eric 'Winkle' Brown, the British test pilot who flew more aircraft than any other in history, was less impressed. He said it suffered poor control, and a "particular sensitivity fore and aft which coupled with the indifferent view from the cockpit, made the glider a touchy proposition for landing in confined spaces. The thought of a medium tank appended to it makes the mind boggle. It seemed a good idea at the time but..."

The full-sized version of the Bat was never made. "The Bat was a way of taking something to the battlefield, but the problem was they never really had the something," says Winchester.

Britain ditched the idea of a flying tank. Instead, it built a glider large enough to carry one – the Hamilcar. The order to produce a glider big enough to carry a tank had come from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill himself in 1940. The cumbersome Hamilcar was big enough to carry a Tetrarch two-man tank, which could be driven through the open front doors of the glider after it had come to rest. They were used in the D-Day landings but encountered the same problems as the T-60 – the Tetrarch was as big as you could get into a glider and still get it into the air, but woefully under-armoured and under-gunned for combat against German tanks. The similar Locust tank built by the Americans, which could also fit inside a Hamilcar, suffered from the same issues.

Charles E Brown/RAF Museum/Getty Images

Charles E Brown/RAF Museum/Getty ImagesEighty years after its only flight, Winchester says the A-40 showed an interesting concept, but was ultimately a dead end. "There was effort involved in building these wings for one-off flights, and their vulnerability – you could see them from miles away and they wouldn't be able to move very quickly if they were in danger."

The advent of large helicopters and dedicated military transports after the end of World War Two rendered the flying tank idea redundant. During the Cold War, the Soviets devised several vehicles that could be parachuted to the ground with their crew inside. The vehicles were loaded into pallets with parachutes attached, and a special rocket system which fired when the pallet neared the ground. The rockets significantly slowed the descent, and allowed the vehicles to instantly head into battle.

In the US, one small tank was able to be delivered in an even more hair-raising fashion. The M551 Sheridan would be loaded onto a metal pallet with parachutes, and the parachutes opened while still inside the aircraft. The force of the parachute opening drags the pallet out the aircraft, with the pallet taking most of the force of the landing. The crew, however, had to parachute to the ground separately from another plane. (You can see a video of a Sheridan being landed in dramatic fashion here.)

The winged tank concept might have crashed to earth, but the dream of tanks from the air didn't die.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List" – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.