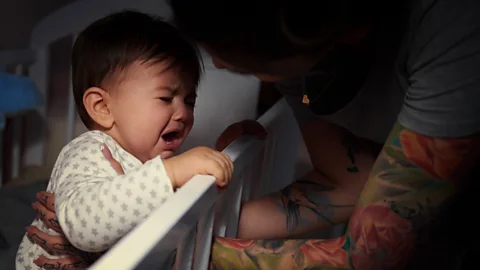

What really happens when babies are left to cry it out?

Alamy

AlamySome parents see "sleep training" as the key to a good night's rest. Others argue that it's distressing for babies. What do scientists say about its risks and benefits?

In 2015, Wendy Hall, a paediatric sleep researcher based in Canada, studied 235 families of six- to eight-month-old babies. The purpose: to see if sleep training worked.

By its broadest definition, sleep training can refer to any strategy used by parents to encourage their babies to sleep at night – which can be as simple as implementing a nighttime routine or knowing how to read an infant's tiredness cues. Tips like these were an important part of Hall's intervention.

Best of 2022

This article is part of BBC Future's "Best of 2022" collection, where we bring you some of our favourite stories from the past 12 months. Discover more of our picks here.

So was a strategy that has become commonly associated with "sleep training" and tends to be far more divisive: encouraging babies to put themselves to sleep without their parents' help, including when they wake up at night, by limiting or changing a parent's response to their child. This may mean a parent is present, but refrains from picking up or nursing the baby to physically soothe them. It can involve set time intervals where a baby is left alone, punctuated by parent check-ins. Or, in the cold-turkey approach, it may mean leaving the baby and shutting the door. Any of these approaches often mean letting the baby cry – hence the common, if increasingly unpopular, moniker "cry-it-out".

(Read part one of this two-part series: the biggest myths of baby sleep).

In global terms, the idea of "training" babies to sleep alone and unaided is uncommon. Modern Mayan mothers, for example, expressed shock when they heard that in the US, babies were put to sleep in a separate room. But in North America, Australia and parts of Europe, many families swear by some form of the technique. Parents can be especially willing to give it a shot when broken nights begin to affect the entire family's wellbeing – poor baby sleep is associated with maternal depression and poor maternal health, for example. In the US, more than six in 10 parenting advice books endorse some form of "cry-it-out". Half of parents who responded to questionnaires in Canada and Australia and one-third of parents surveyed in Switzerland and Germany said they've tried it (although the surveys are not necessarily representative of parents as a whole in these countries, due to the way they were conducted). Around the world, an entire industry is devoted to helping parents sleep train.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn their study, Hall and her team predicted that the babies whose parents were given instructions for sleep training along with advice would sleep better after six weeks than those who were not, with "significantly longer longest sleep periods and significantly fewer night wakes".

This would be in line with existing findings. Dozens of studies say they have found sleep interventions effective; paediatricians routinely recommend sleep training in countries like the United States and Australia (although infant mental health professionals often do not). However, research is never perfect, and many of those prior studies had attracted some criticism – which Hall was hoping to address.

For one, relatively few studies on sleep training have met the gold standard of scientific research: trials where participants are randomly allocated to receiving the intervention, that have a control group that did not receive the intervention (especially important with sleep research, since most babies naturally sleep in longer stretches over time), and that have enough participants to detect effects.

A number of studies, for example, have been non-randomised, with parents deciding on the method of treatment themselves. This makes it hard to prove cause and effect. For example, parents who have reason to think their babies will only cry for a short while (or not at all), then fall asleep, may be more open to trying out controlled crying to begin with – which could skew results to make it seem more effective than it is. Alternately, it could be parents whose babies really struggle to fall asleep by themselves that are more drawn to the method, making it look less effective than it is. And, of course, the difficulty of studying something like sleep training is that even in a randomised trial, parents assigned a controlled crying method may decide against it – so a "perfect" study is impossible to set up. Many trials often have high drop-out rates, meaning parents who found sleep training especially difficult may not have their experiences reflected in the results.

Meanwhile, the majority of studies rely on "parent report", such as questionnaire responses or sleep diaries kept by the parents, rather than using an objective measure to determine when a baby is awake or asleep. But if a child has learned not to cry when he wakes, then his parents might not wake, either – which could lead them to report that their child slept through the night regardless of what happened.

There is also the problem of confirmation bias: if parents expect an intervention to help their child's sleep, then they may be more likely to see that child's sleep as having improved after an intervention.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHall's study – involving 235 babies and their parents – was designed to respond to some of these criticisms. As a randomised controlled trial, half of the parents were instructed in what's called either "graduated extinction", "controlled comforting" or "controlled crying": soothing a crying baby for short increments, then leaving them for the same amount of time, with intervals gradually getting longer regardless of the child's response. For parents who were "really uncomfortable" leaving their child crying alone in the room, Hall says, the researchers advised staying in the room – but not picking the child up – in an approach called "camping out".

The intervention group also received tips and information about infant sleep, such as myth-busting the idea that fewer naps would lead to more nighttime sleep. (It's worth noting that this mix of a controlled crying method with other advice is common in studies examining sleep training, but makes it more difficult to parse which, if any, results are from the controlled crying alone.) To ensure both groups received some kind of instruction, the control group parents received information about infant safety.

As well as asking parents to record sleep diaries, Hall's study included actigraphy, which uses wearable devices to monitor movements to assess sleep-wake patterns.

When the researchers compared sleep diaries, they found that parents who had sleep-trained thought their babies woke less at night and slept for longer periods. But when they analysed the sleep-wake patterns as shown through actigraphy, they found something else: the sleep-trained infants were waking up just as often as the ones in the control group. "At six weeks, there was no difference between the intervention and control groups for mean change in actigraphic wakes or long wake episodes," they wrote.

In other words, parents who sleep-trained their babies thought their babies were waking less. But, according to the objective sleep measure, the infants were waking just as often – they just weren't waking up their parents.

To Hall, this shows the intervention was a success. "What we were trying to do was help the parents to teach the kids to self-soothe," she says. "So in effect, we weren't saying that they wouldn't wake. We were saying that they would wake, but they wouldn't have to signal their parents. They could go back down into the next sleep cycle."

The actigraphy did find that sleep training improved one measure of the babies' sleep: their longest sleep period. That was an improvement of 8.5%, with sleep-trained infants sleeping a 204-minute stretch compared to 188 minutes for the other babies.

Another part of her hypothesis also proved correct. Her team expected that parents who did the intervention would report having better moods, higher-quality sleep and less fatigue. In a finding that won't surprise anyone who has rocked or nursed an infant to sleep several times a night, this proved to be true – and, for many experts and parents, is a key upside of sleep training.

But for anyone who has ever read, Googled, or been served social media ads about infant sleep, the fact that sleep training researchers believe training isn't meant to reduce the number of times a baby wakes – and that it might extend their longest sleep stretch by an average of just 16 minutes – might come as a surprise.

The origins of "cry it out"

Sleep training is a relatively new phenomenon, even in countries where it is now quite common. As BBC Future has covered before, before the 19th Century, new parents didn't seem to be particularly concerned about their infants' sleep. This changed as the Industrial Revolution brought longer work days and as the Victorian era emphasised independence, even among babies.

In 1892, the "father of paediatrics", Emmett Holt, went so far as to argue that crying alone was good for children: "in the newly born infant, the cry expands the lungs", he wrote in his popular parenting manual The Care and Feeding of Children. A baby "should simply be allowed to 'cry it out'. This often requires an hour, and in extreme cases, two or three hours. A second struggle will seldom last more than 10 or 15 minutes and a third will rarely be necessary."

It wasn't until the 1980s, however, that the first official cry-it-out "programmes" were introduced. In 1985, Richard Ferber advocated what he called the "controlled crying" or "graduated extinction" method, letting a child cry for longer and longer periods. (He later said he'd been misunderstood and, contrary to popular belief, that he wouldn't suggest this approach for every child that doesn't sleep well.) In 1987, Marc Weissbluth advised simply putting the infant in his crib and closing the door – dubbed "unmodified extinction".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith some variations, these are largely the versions of sleep training that have persisted, with one 2006 study of 40 popular parenting books finding that twice as many promoted cry-it-out as opposed it. Some books suggest following some form of controlled crying even for newborns.

It's worth noting that even researchers who advocate for sleep interventions, including Hall, think starting so young – any time before six months old, in fact – is a mistake. They also say they would not recommend sleep training for children who could be more prone to psychological damage, including babies who have experienced trauma or been in foster care, or babies with an anxious or sensitive temperament. (Breastfeeding mothers have an additional reason to wait until six months to sleep train, say lactation experts, since early night-weaning may reduce supply.)

Sleep training strategies for babies under six months old are unlikely to work in any case, researchers have found. "The belief that behavioural intervention for sleep in the first six months of life improves outcomes for mothers and babies is historically constructed, overlooks feeding problems, and biases interpretation of data," one review of 20 years' worth of relevant studies put it. "These strategies have not been shown to decrease infant crying, prevent sleep and behavioural problems in later childhood, or protect against postnatal depression."

In addition, the researchers wrote, these strategies risk "unintended outcomes" – including increased crying, an early stop to breastfeeding, worsened maternal anxiety, and, if the infant is required to sleep either day or night in a separate room, an increased risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

Hall once received a telephone call from a concerned grandmother, she says, saying that her son and his wife had taken their three-month-old to a sleep trainer. "The sleep trainer had been basically really hard line, and this kid was now seven months old and was having huge attachment issues," Hall says. "I just wrote her back and said, no one should ever do that to a three-month-old. They don't have object permanence, they don't know that if you're not in the room you haven't disappeared from the planet. It's psychologically damaging.

"And this is the problem with having a lot of people out there who just put up a shingle and start working with parents and telling them what they should or shouldn't do, without an understanding of what they're potentially doing to these babies."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOlder babies' reactions can vary. For some, tears are brief or non-existent. For others, it can be hours of crying, even to the point of vomiting (common enough to be a frequent topic of conversation on sleep-training forums and addressed by baby sleep books including Ferber's). And while methods like camping out – where parents stay in the room but don't pick up, nurse or cuddle the baby – often are considered gentler, they can upset and confuse some babies more than harder-line strategies and tend to take longer.

Either way, many parents feel sleep training is a necessary rite of passage – not only to get a good night's sleep themselves, but because they're told that their babies will sleep better, longer and more deeply, and that they need this to thrive. This refrain is especially common in the world of sleep coaching, an unregulated industry where consultation fees can be hundreds of dollars.

But that's not quite what the research shows.

This article is the second part of a two-part special Family Tree report by Amanda Ruggeri on safe and healthy baby sleep. Read the first part here, on the biggest myths of baby sleep.

Crying it out – but still waking up

One of the few long-term studies done on sleep training, for example, compared eight-month-old babies who were trained using controlled crying (waiting longer and longer before responding to cries), or camping out (sitting with the baby until they fall asleep without picking them up, and gradually moving further and further away), versus continuing to respond to their babies as normal. All of the babies in the trial, conducted in Australia, were described by their mothers as having sleep problems.

In questionnaires they filled out, some of the mothers did report that sleep training helped their babies in the short term. But not all. Eighty-four percent of those who used controlled crying, and 49% of those who used camping out, said those approaches were helpful. (It's also worth noting that the intervention that the most mothers rated highest was very different: "having someone to talk to", seen as helpful by 95%.)

And for those who did find a form of sleep training helpful, effects didn't necessarily last. Two months after the intervention, when the babies were 10 months old, 56% of sleep-training and 68% of the other mothers reported that their babies still had sleep problems. When the infants were 12 months, 39% of sleep-training versus 55% of the other mothers did.

This doesn't just mean that sleep training may not work for every baby. It also means that, for the families which did find sleep training effective, it often needs to be repeated for the effects to last. This is backed up by other research: one Canadian questionnaire found that, on average, parents tried controlled crying between two and five times in their baby's first year.

Longer-term, the Australian study found that any parent-reported improvements in sleep from sleep training disappeared by age two.

When the children were six years old, the researchers found no difference on any measure – negative or positive – between those who were sleep trained and those who weren't, including in their sleep patterns, behaviour, attachment, or cortisol levels.

"What we found was no difference to children's sleep, no difference to children's behaviour, and parents were no more harsh, abusive or disengaged from their children," says Harriet Hiscock, one of the study's authors and a fellow at Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council.

The study's finding that sleep training can reduce sleep problems for some families in the short term, meanwhile, is consistent with a large body of research. One authoritative 2006 review of 52 studies found that more than 80% of children who received an intervention (including strategies other than cry-it-out methods, like implementing a bedtime routine) demonstrated "clinically significant improvement that was maintained for three to six months".

But there was no objective sleep measure used in more than 77% of the studies included in the 2006 review – part of the reason why, of the 52 studies reviewed, the researchers considered only 11 of them to have high-quality data. There also was no objective measure used in Hiscock's study. As one review of sleep training research put it, "there are weaknesses" even in many of the randomised controlled trials, "as many intervention studies have used parental reports, questionnaires and diaries, and not objective measurements such as actigraphy data, as outcomes".

Research conducted with an objective measure such as actigraphy, on the other hand, has found no real difference in sleep between infants that were sleep-trained and those who were not. Hall's study is not the only one. One Canadian study of 246 mothers and their newborns found "no significant differences" in number of wakes or amount of sleep between the infants whose mothers received information on strategies to optimise their babies' sleep, and those who did not. Interestingly, the mothers received this advice slept just six minutes longer than those who did not. A study of 802 families in New Zealand found that, there was "no significant intervention effect on sleep outcomes" at six months, with night wakes reducing by 8% and sleep duration increasing by six minutes in babies who were left to fall asleep independently, compared to babies who were rocked or fed to sleep.

And one very small study of 43 infants which compared three groups – controlled crying, bedtime fading (where babies are put to bed so late that they drop off easily, with bedtime then being brought forward gradually), and a control group – was widely reported when it was published as showing sleep training to be successful, with parents in the non-control groups reporting that their babies woke less and slept longer. But, again, that wasn't found with an objective measure. As the study's authors noted, "no significant sleep changes were found by using objective actigraphy, suggesting sleep diaries and actigraphy measure different phenomena (eg, infants' absence of crying by parents vs infants' movements, respectively), further suggesting infants may still experience wakefulness but do not signal to parents".

Sleep researcher Jodi Mindell, associate director of the Sleep Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and a proponent of sleep training herself, says the reason for this is simple: sleep training's main goal is not to keep babies from waking, or to help them get more sleep. It's to teach them to go back to sleep by themselves, rather than waking their parents.

"All babies wake frequently during the night. It's just whether or not they have the skill to fall back to sleep independently," she says.

"I don't expect babies to wake less frequently. I don't always expect that they're going to sleep more on an objective measure."

These frequent wakes may be tough on parents, but they play an important role in keeping babies safe and healthy. As we've covered previously, babies have evolved to wake frequently for nutrition, caregiving and their own protection, including against SIDS.

Even when done as a randomised controlled trial with an objective measure, meanwhile, sleep training research has other challenges. There is some evidence, for example, that trial participants may feel more pressure to follow through a sleep intervention than they would otherwise, raising questions about how applicable these findings are to everyday parents – a phenomenon that is hardly unique to paediatric sleep research.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTake the questionnaire in Canada: only 14% of parents reported that controlled crying eliminated all night wakings, and almost half said it didn't reduce wakings at all – results, the researchers wrote, which indicate "that parents in the community are experiencing considerably less success with graduated extinction than parents in clinical/research setting".

The discrepancy makes sense, especially if you consider that many of these trials have been run by sleep clinics or their researchers, says Helen Ball, the director of the Durham Infancy and Sleep Centre, professor of anthropology at Durham University and a long-time critic of cry-it-out methods of sleep training. "The people who run those trials have a particular mindset," she says – for example, that sleep training works – which may translate to study participants being more committed to the intervention.

"I'm always somewhat sceptical that the data that these studies produce are actually applicable to real life."

Soothed or stressed?

If sleep-trained babies are still waking frequently, just not crying or signalling, this points to a different debate at the heart of sleep training. When they wake, are these babies actually learning to calm themselves down from a stressed state (emotionally "self-regulating")? Or are they just as stressed and in need of caregiving when they wake, but have simply learned that if they cry, no one will respond?

Many sleep training researchers firmly believe the former. "Don't underestimate the abilities of children to self-regulate," says Hall, the paediatric sleep researcher who used actigraphy in her study of 235 Canadian families. "Parents can help them learn to self-regulate by giving them opportunities to self-regulate. That's how you can look at self-soothing – it's an opportunity to calm themselves down."

It's difficult to measure objectively whether babies are truly soothing themselves, or have just given up calling for help.

One way could be to measure cortisol, which is often known as the stress hormone. But cortisol rises and falls in response to factors besides stress, and the studies that have measured it have had mixed results. One found that the babies' cortisol levels were elevated right after a sleep intervention, but there was no control group of un-trained babies to compare it to. The small study of 43 infants found that cortisol declined, but it didn't measure cortisol until a week after the intervention. And in an attempt to find out whether sleep training led to elevated stress levels long-term, a third study, Hiscock's longitudinal study in Australia, took cortisol samples five years later and found no difference between the cohorts.

"I personally have an issue with the cortisol studies," says Mindell. "Cortisol changes throughout the day. Even sampling cortisol is very difficult. It's based on many things, including how many hours a person has been awake, how it's sampled – it's a complicated thing. People often think 'oh, if we measure cortisol, we'll know if the baby's stressed or not stressed'."

Even the term "self-soothing" has a confusing history. Coined by sleep researcher Thomas Anders in the 1970s, it's often used synonymously with the idea that babies can self-regulate. For Anders, however, a self-soothing baby was simply one who put themselves back to sleep without parental intervention – he wasn't trying to quantify their stress levels.

Of the few studies that have looked at the short- to longer-term outcomes of sleep training, none have found an effect on a baby's attachment or mental health. Hiscock's study, for example, the largest and longest longitudinal study done on sleep training, found sleep-trained children were no more likely to be insecurely attached to their caregiver at six years of age than their peers. (Experts like Hiscock say they aren't aware of any studies that look at potential long-term effects of cold-turkey cry-it-out, just at modified extinction. They also examined healthy babies at least six months old. So these findings aren't necessarily applicable to infants trained at younger ages, or in other ways.)

Like other longitudinal studies, Hiscock's lost touch with a number of families when it was time for the final follow-up: 101 of the original 326. That means it is theoretically possible that the sleep training did affect some children in either a negative or positive way long-term, but that their experiences weren't captured. It's more likely, though, that any effects of a single intervention simply "washed out" after six years, says Hiscock.

The upsides of responding

Another way to examine the self-regulation question is to consider babies' developing brains – and their limitations. Human babies are born very neurologically immature compared with other mammals, with brains around one-third of the size of an adult's. The prefrontal cortex, the "home" of emotional regulation in the brain, is one of the last parts of the brain to mature, not developing fully until one's mid-20s.

As a result, throughout infancy and toddlerhood, the brain relies on "co-regulation" – the aid of a soothing caregiver – to calm down. In a position adopted by the American Academy of Pediatrics, for example, the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child defines a "positive" stress response as one that results from stress that is brief, "mild to moderate" and which hinges on "the availability of a caring and responsive adult who helps the child cope with the stressor, thereby providing a protective effect that facilitates the return of the stress response systems back to baseline status".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn particular, one of the most crucial periods for developing emotional regulation is from six to 12 months, says Dan Siegel, clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles' School of Medicine and author of numerous books on child development including The Whole-Brain Child. "The second half of the first year of life is a big moment of learning to regulate yourself," he says. For that reason, he says, there may be an argument for waiting at least until after the first year to sleep train.

While cortisol measurements need to be taken with a grain of salt, scientists point out that studies consistently show that babies of less responsive parents have higher cortisol levels, particularly after a stressful event. Researchers have found, for example, that newborns whose mothers were more "sensitive" to them during a bath – defined as being aware of, and responding appropriately and promptly to, an infant's communications – better regulated their cortisol levels when they were taken out. The cortisol levels of seven-month-olds with less sensitive mothers also took longer to regulate after a stressful situation.

This is no less true overnight. One study found that responding to three-, six- and nine-month-old infants overnight was associated with lower infant cortisol levels. Another found that the young infants of mothers who were emotionally available at bedtime – including responding to their babies within one minute of crying – had lower cortisol levels than babies of less responsive mothers (though, again, we need to be cautious about over-interpreting the significance of cortisol findings). "Because infants may be especially tired at bedtime, they may have reduced tolerance for stress and therefore require additional help in regulating their emotions," the researchers wrote. "Thus, parents' ability to soothe their children and create a quiet, safe environment which allows them to fall asleep may be particularly relevant to infant regulatory processes such as cortisol secretion."

Meanwhile, a large body of research has shown that a caregiver's consistent responsiveness is "most often associated with language, cognitive and psychosocial development", including better language acquisition, fewer behavioural issues and less aggression, higher intelligence and more secure attachment.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor researchers like those who found babies had lower cortisol when responded to overnight, the risk of stress is longer term. "Because early experiences of stress may program the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis to be more stress reactive, increasing risk of physical and mental health problems in later life, our results suggest that parenting in infant sleep contexts may play an important role in shaping how the child responds to stress across childhood," they wrote.

Plus, for pre-verbal infants, crying is one of their only forms of communication, particularly if they are trying to wake sleeping parents – leading to concerns about the impact of an intervention specifically aimed to "extinguish" their cries. (Critics of cry-it-out note that this intention and end goal is one of the differences between a baby crying in sleep training versus in a situation where a baby is crying but a parent may be unable to provide their usual level of comforting, such as while driving.)

And if an infant is regularly waking frequently or having difficulty settling, it could be the sign of an underlying health issue like reflux or a tongue tie, so it's important to rule out any medical reasons for sleep problems first.

Sleep training critics also argue that we may simply not be asking the right questions, or using the right scientific tools, to fully understand the potential risks.

"I think [attachment and cortisol levels] are just two things that we've got tools to measure. So that's why they're picked," says Ball.

Different personalities

There is a further complicating factor: the degree to which a baby's individual personality plays a part in whether they put themselves to sleep independently on their own, or whether sleep training is a success.

For example, research has found that the more parents actively help their infants in going to sleep, the longer it can take those babies to learn to sleep independently. This is often interpreted to mean that you must leave your baby to it or sleep train for them to become an independent sleeper. But these were observational studies – so it could be, instead, that babies who need soothing to go to sleep have parents who respond by soothing them.

Indeed, other research has found that babies with more difficult temperaments are also poorer sleepers – and parents respond to them more at night. One longitudinal study found that if babies slept poorly, their parents were more likely to engage in behaviours to help them settle even when they were toddlers. The results "suggest that early sleep problems are more predictive of future sleep disturbances than are intervening parental behaviours", the researchers write.

Recent research also has found that children with more sensitive temperaments (sometimes nicknamed "orchid children") can react more strongly to their environments – such as being more negatively affected by stress.

Indeed, some children remain calm and collected even when a caregiver walks away momentarily, sleep researchers say. Others become upset and frustrated. This is a sign, they say, that some children learn to self-regulate earlier than others.

"It means that you have to be really careful when you're giving parents suggestions about how to manage sleep problems, that you're taking those differences in separation anxiety into account," says Hall.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThese differences in temperament may help explain why sleep training (or, for that matter, suggestions such as "put your baby down drowsy but awake") seems to work brilliantly for some families, who find their baby barely grizzles before drifting off, and don't work at all for others, whose infants might sob for hours and days on end. The questionnaire of Canadian parents, for example, found that 25% reported using controlled crying for bouts of more than two weeks at a time – 13% even tried for more than a month. (Mindell's advice: "Stick with it for seven to 10 days, and after seven to 10 days, if it's not working, take a break. Don't just keep going down that path.")

It's also worth noting that in their top-line results, studies normally report on the average outcome, which doesn't show the variation of every family's experience, especially those at the extremes – such as those who found sleep training a smashing success, or a total failure.

Given those individual differences, when talking about helping a child with any new skill, Siegel says, he encourages parents to consider the "zone of proximal development". The lower part of the zone is what the child can do on their own, while the top part is a more complex skill that you must do with a child. "The best imparting of skills is within the zone. 'Let me teach you how to do it. Here's how you brush your teeth.' 'Now, let's see if you can do it on your own. Oh, you really can't, okay.' 'Okay, now you're a month older, and now you can'," he says.

Not everyone believes that falling asleep independently is a skill, pointing out that it normally happens developmentally with or without teaching and that, unlike, say, crawling, it can be something that comes and goes (a child might self-settle at nursery but not at home, or for a few months and then stop). But if it is a skill, then it's most effective to work within that zone, not pushing a child past their edge, Siegel says.

So how do you know what the edge is? Does 15 minutes of crying mean the step you're trying to teach is too advanced for the child at that time? An hour?

"I can't answer as a scientist," says Siegel. "But intuitively, as a parent, as a therapist, as an educator, if within five minutes, your child is not finding a way to bring them into a calmer state, then their zone of proximal development has been pushed, I think, beyond its limits. And then you would want to give them support."

The difficulty is that sleep training is based on the understanding that you are "rewarding" a child's crying if you respond to them, teaching them that you will respond if they signal you – so this is exactly what extinction-based programmes say not to do.

Family fatigue

Researchers tend to focus on sleep training's potential impact on babies – which makes sense, since they're the most vulnerable, helpless members of the family unit. But sleep training obviously affects the rest of the family, too.

It's worth noting that it can go either way: some parents deeply regret using an extinction method with their little ones, for example, especially if it goes against their instincts. On average, the Canadian questionnaire found, parents tend to find controlled crying "quite stressful" for both themselves and their child. "You risk parents' mental health by overriding their instincts, because I think that makes parents feel anxious about what they want to be doing (comforting their baby) versus what they end up doing (leaving them to cry). And then I think it's really difficult to know what you're risking on behalf of the baby," says Ball.

What you hear more frequently, however, is that sleep training can help families, and some research backs this up. Hiscock's study found that the mothers of sleep-trained babies were less likely to be depressed when the baby was two years old. Other research has found that the fathers of four-month-olds with sleep problems had greater anger towards their babies and more depressive symptoms, and that infant sleep problems were associated with poorer health in both mothers and fathers.

Family Tree

This article is part of Family Tree, a series of features from the BBC that explore the issues and opportunities that parents, children and families face all over the world. You might also be interested in some other stories about babies' and children's wellbeing:

You can also climb new branches of the Family Tree on BBC Worklife.

A parent's mental health may in turn affect the infant's actual sleep patterns: one small study using actigraphy found that depressed mothers were more likely to have babies who have more disturbed sleep. A parent's poor mental health can also put babies at a higher risk of insecure attachment.

Hall's study also looked at this element. While actigraphy showed that babies slept and woke similarly whether they were sleep trained or not, their parents' perceptions of the situation were very different. At six weeks, parents of just 4% of the sleep-trained infants versus 14% of the control-group infants reported that their child had a severe sleep problem. And the parents' levels of fatigue, sleep quality, and depressed mood all improved significantly.

While there are some caveats to the findings – such as that they may apply mostly to mothers who already have symptoms of depression – many experts see this as a strong argument for using sleep training to ultimately boost the whole family's wellbeing.

"If we're not healthy and functioning as parents, it's very hard to look after our children and give them the love and parenting that they need," says Hiscock. "There are some people who say we have to put the baby first and don't worry about the parent, and I just think that's wrong, because if you don't have a mum who's healthy and thriving, it's hard to have a baby who's healthy and thriving. It's a relationship dynamic – it's not one or the other."

Academics who oppose sleep training agree that these factors are important. Their issue, they say, is with the fact that many parents often are simply advised to sleep train, without being told about nuances – such as that it doesn't work for every baby or that it often needs to be repeated – and that they aren't presented with other options.

"I think it's often sold to parents who feel like they're in a tight spot, and they've got to sleep train their child in order to be able to survive. But actually, I think we need to help them come up with other strategies way before they get to that crisis point," says Ball.

One strategy that both Ball and James McKenna, the founder and director of the Mother-Baby Behavioral Sleep Laboratory at the University of Notre Dame, have found works for some low-risk families is bedsharing, or cosleeping. Small studies have found that mothers report having better sleep when bedsharing than when sleeping separately from their infants, even though objective measures find only modest changes to their sleep, and while research has shown that while bedsharing infants wake more frequently, their total awake time doesn't differ from solitary sleepers. (The Lullaby Trust lists guidelines for safe bedsharing here).

Kathryn O'Donnell

Kathryn O'DonnellThere are other strategies which researchers on both sides of the debate agree on. Implementing a bedtime routine is one. One review co-authored by Mindell found that following a bedtime routine is linked to children falling asleep faster, waking less and sleeping for longer. Putting a routine in place even worked when it was the only sleep strategy families followed: one randomised controlled trial of 405 children aged seven to 36 months found that those who were randomly assigned a three-step routine of a bath, massage or lotion, and a quiet activity like reading slept better and longer than babies who were not assigned a routine.

Ball, who recently has worked with other researchers to adapt the Australian sleep programme Possums into a version for UK NHS practitioners, also points out that there are many ways in which we often make things even harder for ourselves.

"We have this cultural obsession with getting children in bed at seven o'clock at night," she says. "But most babies are going to need another feed before their parents go to bed. And usually when a baby falls asleep, the first block of sleep is the longest one of the night." That first four hours of sleep also is when we have most of our deep sleep. "So if you align your period of deepest sleep with the time your baby gets its longest stretch of sleep by going to bed when they do, you're maximising the benefit. Why are we sitting downstairs watching television? And when you say stuff like that to parents, some of them are like, 'We want some us time, we want some child-free time.' Well, then that's your choice. You're trading that off against sleep."

Giving parents more support and information may help, too. Remember the intervention that was seen as helpful to the most mothers in Hiscock's longitudinal study: "having someone to talk to". A higher percentage of parents also scored learning about what made their child's sleep worse and about normal sleep patterns as helpful than said the same of controlled crying – and receiving advice on how to look after their own well-being and getting information about managing dummies was rated by more mothers than was camping out.

More broadly, critics also point out that baby sleep is a societal issue. Many modern families rely on two incomes and have little or no parental leave – aspects that pressure parents to get solid night's sleep quickly, often long before an infant would be developmentally ready to do it on their own, without prodding. It's common to see calls for better (or any) maternity or paternity leave among anti-cry-it-out circles.

Whether families choose to sleep train or not, there is good news: eventually, with or without training, most children stop requiring a caregiver's help at night.

One study of more than 4,000 children, for example, found that 71% of five-month-olds who regularly woke at night stopped night wakes by 20 months, and 89% ceased by 4.5 years old. (Those who woke frequently as infants were also more likely to wake as pre-schoolers, but again, it's unclear how much of this is down to temperament: a baby who wakes could also be more likely to be a child who wakes).

The bottom line on sleep training?

"It's only worth doing when parents want to do it and see it as an issue they need help with," says Hiscock. "I meet parents who might be up three, four, five times a night, but they're happy to be, or they're coping and managing with that."

Mindell agrees. "If you're rocking a baby to sleep at four months of age, they're waking once a night, it's working for the family, why would you mess with success? Why would you do sleep training?

"We only really recommend it when there's a problem," she says.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.