Time capsule 2020: The 37 objects that defined the year

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontIf we were to create a time capsule of objects that captured life in 2020, what might we choose?

The eyes of future historians are on us now. The year 2020 has been tumultuous, disruptive, exhausting, and pivotal – and one day, our great-grandchildren may wonder what it was like to live through these times. Yet with all that has happened over the past 12 months, only snapshots may be recorded in the long-term: the most salient traumas and the most dramatic turning points. History often charts the stories of the privileged, the powerful or the notorious, but cannot capture all of human experience.

So, what might we wish future generations to know about this year? If you could leave behind an object that spoke of 2020, what would it be?

As the year comes to an end, BBC Future decided to assemble a virtual time capsule – a list of objects that matter, and that tomorrow's generations should know about, 100 years from now.

Collaborating with the School of International Futures, we asked their network and global next-generation fellows to nominate a series of objects. To that list, we added a few extra submissions from other future thinkers – plus one or two of our own.

Some might wish to forget this year. However, the objects we collated are intended to be symbols of acts, experiences, ideas and changes that are worth preserving. We asked our submitters to propose items they believe deserve attention and memorialisation during these turbulent times. As well as the trauma, this year has also brought some positive changes that we don't want to lose, moments when things got a little bit better amid the chaos, local wisdom or inspiration, as well as warnings that we might hope will not be forgotten.

Time capsules have always been about what a society wishes to remember and pass on: its best version of itself, projected into the future. They are usually subjective, often eclectic, and always tell a human story. And that's exactly what we got when we asked for submissions.

Here's what we chose:

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontPerhaps the most obvious item to place in our hypothetical time capsule would be the face mask. In 10 years' time, you might find yours in a drawer and marvel at how it became such a dominant part of life in 2020.

We had a couple of variants on this theme. One was for masks with company logos (Mansi Parikh), to capture the idea that the world remained just as consumerised as it was pre-pandemic. Until 2020, personal protective equipment (PPE) was largely limited to health workers, builders and other professionals that needed protecting. "That shift from specialised equipment to a mainstream consumer product is very iconic of 2020," says Parikh.

Meanwhile, Angela Henshall found the smaller face masks for toddlers particularly evocative. With their cartoon characters printed on the front, they marked a sharp contrast between the dangers of the disease and the innocence of childhood.

But if we had to include only one item in the "mask" category it would be the needle and thread (Pupul Bisht). "The pen is mightier than the sword goes the saying, but in 2020 the humble needle and thread emerged as two of the mightiest tools against the deadly pandemic," says Bisht. When masks were in short supply, "some old cloth scraps, a needle and some thread went a long way for communities to be able to protect themselves. These tiny little objects often tucked away in old cookie tins made it possible to save lives".

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontIn the early lockdowns when shop shelves emptied and supply chains broke down, a spirit of self-reliance and make-do-and-mend was essential to get through times of shortage and restriction.

Until stocks were replenished, many were forced to turn to DIY disinfectants, such as homemade hand sanitiser (which, it should be noted, is not recommended unless you really have to and know what you're doing). Christy Casey nominated a plastic disposable wipe container filled with cloth scraps. "My favourite DIY solution was my mum's reusable bleach wipes," Casey explains. "It's such a simple solution: take rags made from T-shirts or other fabric and place them in the container from the disposable set you just finished (or a jar), and add bleach and water."

Meanwhile, other capsule submissions told stories about how their nominators had managed to meet specific, personal needs with a dash of creativity. One submission was for a hand-made candle (Olga Remneva, Anna Peplova, Irina Danilicheva, and Anastasia Evgrafova). "With a little bit of light and scent, one can make his/her/their place nice and cosy. Watching a candle reminded one to look inside, and to find there a whole world," they wrote.

Another was a homemade digital drawing stylus (Rocco Fazzari), constructed using an old pen casing, steel wool and aluminium foil.

And when Amy Charles and her housemate Eleanor found their usual exercise routines disrupted, they made a homemade weight to keep fit. "We bought sand, cement and some toilet piping, and poured the mixture into a lunchbox to create a 5kg (11lb) weight with a handle. It's crude, and can also be used as a doorstop, but it was a fun project."

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontOne suggestion that manages to capture the spirit of make-do-and-mend in a single object was a kintsugi-repaired bowl (Will Park). Kintsugi is a traditional Japanese practice involving refashioning old possessions into new. "Kintsugi involves sealing cracks with lacquer that is then coloured with gold or silver dust. It creates an appearance of veins of rare metal running through the porcelain. The result can be even more beautiful than the original," wrote Park in an article for BBC Future earlier this year.

Home comforts and neighbourhoods

With so much time spent in lockdowns this year, it's perhaps not surprising that many people looked close to home for their inspiration. We had nominations for a set of pyjamas (Deepshikha Dash), a home office chair (Kate Rahme), and the wire of a phone/laptop charger (Iman Jamall) because it enabled connection to the internet and other people.

Other objects offered reminders of a sense of play, such as a chessboard (Shakil Ahmed) from Bangladesh. Or creativity and home comforts, such as Maggie Greyson's proposal to include a breadknife. Like many, she and her husband discovered sourdough this year, after learning how to make it from a friend who lived near her parent's farm. When they returned home to Toronto, "we tried to buy a breadknife instead of mashing the bread with our dull kitchen knives, but they were out of stock. Two months later, a package came in the mail with the best breadknife we had ever seen".

Many also discovered new ways of getting around this year, which is why one person suggested a pair of running shoes (Maryann D'sa), and another their old mountain bike called Hendrix (Griesham Taan). "I found myself digging out the 17-year-old bike from my father's shed, dusting off cobwebs and oiling the wheels," says Taan. "In a world full of fear and uncertainty – Hendrix, my old mountain bike – gave me a sense of control, freedom, purpose and safety."

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontOne idea for inclusion that spoke to the monotony of lockdown was a hypothetical calendar of views from the same window (Fiona Macdonald). The calendar would be one scene taken multiple times "like a timelapse, as the seasons rush by", explains Macdonald, whose own window view features "bedraggled shrubs, forgotten toys, and the windows of the neighbours opposite".

It's an idea that reminded me of the website Window Swap, which gained popularity this year. People from around the world shared scenes from inside their homes of mountain views or verdant gardens, allowing visitors to instantly transport themselves to a new location.

Solace from local beauty was also the thinking behind the suggestion of a flaming red bombax flower (Pupul Bisht), from New Delhi. "The old seemal tree (English: bombax) outside my window had turned into a flaming red hue by the third week of March like clockwork. Despite everything feeling unfamiliar, the tree brought a sense of normalcy to my days. 2020 made a statement loud and clear – that flowers bloom in dystopias too."

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontHome working was, of course, a luxury that many people did not have this year. With that in mind, we also had a nomination from more than one person for a delivery bag (Olga Remneva and others), in recognition of the way that drivers, shop-workers and many other professions kept the world turning.

Similarly, it would be an omission for us not to include an item that recognises healthcare and care-home workers. In many countries, that object was a child's drawing of a rainbow, a universal message of thanks to those in risky, pressured and stressful environments, looking after the most vulnerable and ill.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontMoving around

Environmental change – for better and worse – was the theme of a few other suggestions, drawing connections between nature close to home and in the broader world.

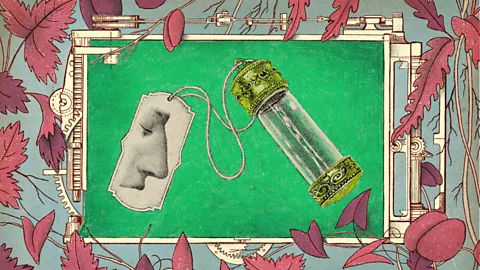

My own nomination for inclusion is a sealed vial of clean city air. Before the pandemic, I would run home from work, and when I stepped through my apartment door, I could often still taste the metallic traffic fumes in my dry throat and nose. During the lockdowns, however, many cities saw air pollution plummet. Harmful particulates will return – in some cases, they already have – but a vial of clean air is a reminder of possibility, and a memory of a less polluted city where it was easier to breathe.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontOther environmental changes in 2020 were less welcome. In particular, we had a number of nominations aiming to capture the memory of this year's wildfires, which came due to the climatic change that was sometimes overlooked this year. The starkest objects proposed were a piece of burnt wood (Leonardo Soares) – "a painful reminder that, despite the existence of a global pandemic, humanity still faces a massive environmental crisis" – and a piece of black granite rock (Paul Brown), from Washpool National Park in New South Wales, Australia. "Charred by fire, shedding its blackened 'skin', the rock survives in landscape utterly devastated by fire, though beginning to regain life – eucalypts, waratahs and ferns regenerating first."

But others submitting in this theme were more hopeful. Rodrigo Mendes, who lives in Brazil where Amazon fires raged, chose an object that captured both a popular pastime of lockdown and what he saw as increased international concern over the fires in his country – a plant in a pot – because plants "require daily care and make us reflect on the importance of biodiversity", he explains.

You may also like:

And a second suggestion from Australia was a pair of dirty gardening gloves from a local community garden (Claire Marshall). "Feeling safe in nature was quite a profound thing to feel after the horrendous bushfires," she explains. Gardening also offered a respite from thinking about the pandemic. "In March we thought everything we touched could harbour the virus (glass, hard surfaces, plastic etc). I remember telling my children 'don’t touch that' a million times, but in the garden, it was safe: the dirt, the leaves, the neighbour's strawberries."

A final development related to the living world and environment this year, which could have long-running impacts, was the rise of artificial meat. Late in the year, lab-grown chicken meat was approved for consumption for the first time, in Singapore. Meanwhile, there's been a dizzying rise in the popularity of plant-based "meat" products already on the market. That's why one capsule submission was a pack of artificial plant-based burgers (Sarah Castell, Stephanie Barrett and the Ipsos Mori Trends and Futures team). By reducing carbon emissions and the farming of animals, these products reflect a potentially broader societal change towards more ethical consumption, say Castell and colleagues. Future generations may see the introduction of healthier artificial meat as "an early signal of the tide turning towards an attitude to wellness that considers the whole planet, as well as the consumer themselves".

Social and political change

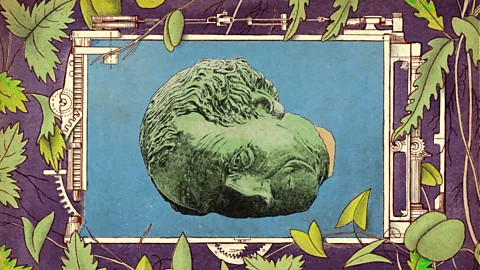

This year was also one of social change, with the rise of the Black Lives Matters movement and other equality protests around the world. To capture these broad and diverse changes in a single object, Samantha Matters proposed the toppled head of a statue. She specifically chose Montreal's statue of John A Macdonald, Canada's first prime minister, which was pulled down by protestors in August because of his links to cruel policies that killed many indigenous people in the 19th Century. Yet it could equally be any one of the many ancestor statues that were either toppled or peacefully reassessed this year.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont"The stories we choose to tell matter, the legacies we immortalise hold meaning," says Matters. "2020 was a time for old stories to land on new ears. This year was not the first to witness such an uprising, but perhaps amid the calamity that we continue to navigate, we will find a way for it to be the last," she continues. "Can we look at these defamed relics of the past not as something to be rebuilt and upheld, but as a symbol of the traumas of a future that will continue to divide us if we cannot find the courage to acknowledge the harms we have caused and make space for collective healing?"

In case you missed it, there was also an election in the US. There was much about that event that was unprecedented, and historians will record in detail what happened for future generations. But one suggestion for the time capsule spoke to a specific facet: the erosion of truth, and the rise of misinformation. Mathew Markman proposed we include a local printed newspaper. It may be an increasingly archaic medium, but it speaks to what we are leaving behind as we move deeper into the digital age, he argues. "While not immune to the perils of politics and propaganda, the printed press is a tangible product that carries the potential to ground our reality in the local community," Markman explains. "It is an allusion to a time when (dis)information was slowed by its corporal form, and that which was most important to us could be found in our immediate surroundings."

Connection and care

One of the more popular themes running through our capsule nominations was the concept of community. While in 2020 there were many points of tension and anger, selfishness and polarisation, a number of our proposers spoke of the relationships they forged, and the neighbourliness they discovered.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontOne nomination we got from Thailand was literally the neighbours (Aline Roldan): "I did not know who they were and suddenly they were the only people I could interact with on a daily basis". (Heartening as this is, we would never dream of burying her neighbours inside a time capsule.)

Another community-minded nomination was the Indian diya (Deepshikha Dash), an oil lamp usually made from clay. "This earthen artefact has been a symbol of hope and victory for centuries and is often seen as the remover of darkness, both literally and figuratively," says Dash. This year, many Indians lit the lamps at the same time: 21:00 for nine minutes, "demonstrating how an old cultural artefact was used to motivate and build hope in the masses, while giving them the strength to unite and move forward during darkness and uncertainty".

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontOther nominations spoke to personal relationships within the pandemic – those created and those missed. One suggestion for inclusion was the hug curtain (Javier Hirschfeld), the slightly strange plastic sheet with arms that allowed relatives and friends to embrace this year without spreading the virus. In this vein of unusual inventions, one person nominated a futuristic piece of clothing called the Micrashell (Leah Zaldi), which looks like a cyberpunk astronaut suit, and allows people to socialise and dance together while remaining distanced.

Maggie Greyson suggested an object that told a specific personal story about friendship: a hand-typed telegram on yellow paper. It was a meaningful thank-you note, she explains, sent by a friend who was struggling after being laid off. Greyson had helped her rediscover her passions. "An old-timey French man with a moustache and postmaster hat showed up at my door with a note of love and gratitude. He delivered a deeply human experience in a hand-typed telegram, on yellow paper. He left his sweet bicycle on the sidewalk and my husband remarked on how beautiful it was."

Virkein Dhar nominated a journal of her drawings that helped to connect her and others via a WhatsApp group this year. Every day between 28 March and 7 November, Dhar's friend read a poem in Hindi, Urdu and English for the group via a WhatsApp audio note, and Dhar drew illustrations in response. The end result was called "226 – Zoon", named after the Kashmiri word for "moon" – "a journal of 226 sheets of drawings, interspersed with snippets of prose and ramblings, hand sewn into an archive of the sense of each day as it has played out in lockdown". The project was captured in this digital archive.

Future gifts

The last category of submissions we received fell under the theme of "gifts to the future".

Erica Bol, from the Netherlands, suggested a set of teaching materials called the Futures Thinking Playbook, which features interactive exercises that Bol hopes could help tomorrow's children anticipate and influence the future. "It is difficult to teach something that doesn’t exist yet, but children can learn the skills to better prepare for the future," she says. "Covid-19 brutally showed us 'change' is around the corner, the world does change, sometimes faster, sometimes slower and we can better prepare for it."

And the final object to go in our time capsule? Roman Krznaric, the author of the book The Good Ancestor, had a mischievous-but-meaningful suggestion: another, smaller time capsule, inside the first one. "On one level this time capsule is a symbol of our desire to communicate with future generations," he explains. "It tells them that we care about the world we are bequeathing them, which is full of risks and possibilities. But the time capsule is also in itself an intergenerational gift we are passing down, which the citizens of the future can fill and themselves pass on to their descendants.

"As each generation passes on a time capsule inside their capsule to the next generation, the time capsules may well become progressively smaller, but they will also become a great chain connecting all generations through time."

So, with that, our time capsule is almost full. But there is room for one or two more objects that we may have missed. What would you want to propose? Let us know on our social media channels below.

When this year becomes a distant memory, and the difficulties it has brought have long since passed, there's little doubt that we'll be glad it is behind us. But that doesn't mean there aren't many things about 2020 that ought to be remembered: the moments of light, the good ideas, the sacrifices, the self-reliance, the relationships, and the communities. To paraphrase the often-quoted wisdom: a society that forgets its past is doomed to repeat it, but a society that forgets its humanity has no future at all.

*Richard Fisher is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @rifish

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

+ Thank you to the following for their creative contributions:

School of International Futures and Next Generation Foresight Practitioners

Pupul Bisht, who coordinated submissions

Shakil Ahmed

Nour Batyne

Erica Bol

Christy Casey

Deepshikha Dash

Virkein Dhar

Maggie Greyson

Iman Jamall

Mathew Markman

Samantha Matters

Rodrigo Mendes

Mansi Parikh

Olga Remneva, Anna Peplova, Irina Danilicheva, and Anastasia Evgrafova from Future Culture Lab

Aline Roldan

Leah Zaidi

BBC.com & others

Amy Charles

Javier Hirschfeld

Roman Krznaric

Leonardo Soares

Fiona Macdonald

Will Park

Griesham Taan