How to rehabilitate old oil supertankers

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe enormous ships that ferry crude oil around the world embody the fossil fuel era and its legacy of pollution. But can they be transformed to be good for the environment?

As you read this, around 10,420 giants are heaving their way across the world’s oceans. Their enormous metal bodies lumber onwards in spite of inclement weather and rough seas.

In their bowels, these beasts are carrying 3.8 billion barrels of crude oil among them, enough to fuel around 420,000 transatlantic flights and for the world’s cars to cover around 3 trillion miles between them. Their sticky cargo is the raw material for billions of plastic bags, combs, trainers, drinking straws, synthetic clothing, toys, water bottles and hundreds of other plastic-based goods that we use in our daily lives.

You might also like:

There are few vessels that better symbolise the achievements and the problems of our thirst for fossil fuels than the oil tanker. Their number include some of the largest moving human-made objects on the planet – vessels of intimidating scale. Without them, our modern lives would grind to a halt. But as they chug relentlessly across the oceans, these supertankers release their own thick plumes of pollution into the atmosphere and, on occasion, into the water.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a world where climate change poses a very real threat – one that could force us to wean ourselves off our fossil fuel habit – the diminishing demand for oil tankers could produce new problems. As renewable energy, bio-based plastics and other sustainable materials reduce our reliance on oil, what will we do with the gigantic vessels that currently carry it around the world?

Like most sea-going ships, they could be sent to the scrapheap, their bodies cannibalised for valuable metal that can be melted down and reused. But disposing of them is a dirty, dangerous and poorly paid business for those who undertake this work in some of the most deprived parts of the world.

There are some, however, who believe that these dirty monoliths of the oil age can instead be rehabilitated – they want to transform them into sources of clean, renewable energy. Engineers believe it is possible to use the vast hull of oil tankers to create floating power stations that can convert the ocean swell into electricity. This is the ambitious plan to create the world’s first “waveships”.

“The current problem with most wave energy projects is that they are fixed in place, close to the shore so they can be connected to the electricity grid,” says Andrew Deaner, managing director of ShipEco Marine, the company behind the waveship project. “This isn’t necessarily where the best waves are. With a ship you are mobile, so you can move to the edge of low-pressure weather systems where the waves are bigger and there is more energy.”

Transforming a supertanker into an environmentally friendly mobile power station draws on other areas of the oil industry for its inspiration. Growing up, Deaner spent a great deal of time on diving support vessels built by his father for installing and repairing oil wells and pipelines on the sea bed. These vessels have special chambers cut through their hulls, known as moon pools, which allow divers and submersible vehicles to be lowered safely into the ocean.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn choppy seas, the water levels in these moon pools can move up and down as waves pass along the length of the ship. This in turn can change the air pressure inside the chamber above the pool of seawater as it rises and falls.

“It works like a giant piston,” says Florent Trarieux, a renewable energy engineer who led tests on the waveship concept in scale models at Cranfield University. “We would put a turbine at the top of the chamber that is driven by the air as it is pulled back and forth by the water. We could put these in columns all down the length of a ship like an oil tanker.”

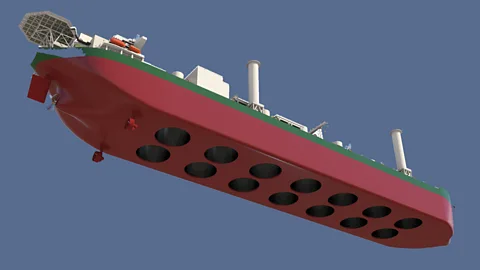

While cutting holes in the bottom of a ship might not seem like the smartest move, tests by Trarieux have shown the huge displacement that oil tankers generate would help to ensure they remain buoyant. Depending on the hull size, the team believe a tanker could have a capacity to produce between 10 and 30 megawatts of electricity. A very large tanker could have up to 35 moon pools, each 20m in diameter, they say.

ShipEco Marine

ShipEco MarineThe technology needed to do this is far from pie-in-the-sky. In the 1970s the Japan Marine Science and Technology Center built a boat shaped buoy that used air turbines at the top of 22 bottomless chambers cut into the hull. But tests of the vessel, which was anchored in the Sea of Japan, showed its ability to absorb energy from the waves was “disappointing”.

More recently, however, engineering giants Siemens have developed a more efficient “hydroair” turbine that can turn the oscillating flow of air inside a water filled chamber into electricity. Another firm, called Ocean Energy, has also built buoys that use a similar principle that are being tested in the Atlantic Ocean.

Like many other wave energy devices, these systems are mounted on platforms that are moored in place and so rely upon the weather at a single spot in the ocean to generate sufficient waves. Wave energy generators also need to be able to transmit the electricity they produce back to shore, and so need to be close to the coast so they can be connected through cables.

Deaner and Trarieux, however, believe this is limiting the potential of wave power. They say that putting oscillating air flow turbines above moon pools on board ships could allow them to chase storms around the oceans to get the best waves.

“Effectively we would be going ‘fishing for energy’,” says Trarieux. Out on the open ocean where unimpeded winds can generate larger waves, the amount of energy that can be generated is many times greater than can be produced in coastal areas. “It is a completely different approach to wave energy.”

ShipEco Marine

ShipEco MarineThe project has already received the backing of the UK government, which funded some of the feasibility studies and scale model tests. These have shown that the tankers can be modified to create moon pools without compromising their strength and stability, according to Trarieux.

The next challenge is getting hold of a suitable ship. Second-hand oil tankers are not cheap and even an ageing, relatively small ship can cost millions of dollars on the open market. But the team believe the prevailing wind could work in their favour as the world moves away from using fossil fuels.

“There are thousands of oil tankers currently in operation and hundreds reaching the end of their service lives every year,” says Trarieux. “All that steel could be cut up and reused, or we could repurpose them to make wave energy.”

The number of large oil tankers being scrapped reached record levels in 2018, with more than 100 vessels being sent for demolition. The majority ended up on beaches in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan where they are taken apart by unskilled workers, often with little or no safety equipment. The life expectancy of those doing this dangerous work at these enormous shipbreaking yards has been estimated to be 20 years lower than the general population in these countries and the industry has faced accusations of human rights abuses. Environmental campaigners have also raised concerns about the hazardous substances and pollutants that leach out from the ships as they are dismantled, which has led to calls for stricter environmental regulations around ship breaking.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesConverting these vessels into waveships could be a tempting alternative to scrapping them. “Transforming old oil tankers, used to ship millions of gallons of oil around the world, into a potential clean energy source is yet another example of the UK leading the global shift to clean growth,” says Claire Perry, energy and clean growth minister in the UK.

But Deaner’s vision goes beyond simply turning them into power stations where the energy will be stored on board in expensive, heavy batteries. Instead, he sees these giant ships becoming floating, self-sustainable factories by putting the electricity they produce to immediate use.

“We are looking at making products onboard so we are not tied to any electricity grid connection,” he says. “We are looking at producing fresh water – we think we could make somewhere between 18,000 and 36,000 tonnes a day before bringing it ashore. We could also make hydrogen or liquid nitrogen, which we could sell to industry.

“But if someone wanted to put a chocolate factory on the deck of our waveship we could actually be manufacturing products as it is being shipped to markets around the world.”

Chris Collaris Design

Chris Collaris DesignBut not everyone is convinced by the idea. Stephen Salter, a leading wave energy expert at the University of Edinburgh who invented one of the early wave energy devices commonly known as Salter’s Duck, says air turbines may struggle to cope with the wide range of flow speeds caused by natural waves on the ocean. He also worries about how resilient an oil tanker would be on the high seas with holes cut in its hull.

“Cutting a round hole raises stress by a factor of three,” he says. “If the tanker designer did a good job, then a great deal of modification will be needed. Any sharp corners will also dissipate lots of energy.”

But there could be some alternative uses for the world’s discarded oil tankers. One New York-based artist recently proposed tipping a 300-metre-long supertanker on its end and anchoring it vertically in a harbour as a visual reminder of the need for mankind to end the fossil fuel era.

A group of Dutch architects have also proposed turning old supertankers into floating public villages that contain shopping malls, concert venues, museums, swimming pools and a public park on the top deck. But the firm behind the concept, Chris Collaris Design, say they have yet to find anyone brave enough to take the concept further.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut anchoring an oil tanker in such a way that it can be safely boarded and used by thousands of people is a tricky problem. Others believe it may be better to turn these enormous steel beasts into something that provides services to people rather than being somewhere they can meet and gather.

A Norwegian company called EnviroNor is developing technology it hopes can be used to convert oil tankers into mobile waste water treatment plants. These offshore treatment plants could then be sent to cities around the world that are struggling with water shortages. EnviroNor say a single tanker could treat the waste water from a city of 250,000 inhabitants. Mooring these converted tankers alongside wind farms, they could also use renewable energy to desalinate water for coastal cities.

But one of the most common current uses for old oil tankers after scrapping is perhaps also the most surprising – turning them into wildlife havens. Oil tankers are more commonly associated with harming marine life due to spills after accidents, but at least 40 of these vessels have been deliberately sunk to create artificial underwater reefs.

“If they are cleaned properly, oil tankers have a very big surface for things to attach to underwater and they will have a long lifespan,” says Dalia Conde, director of science at Species360, an international conservation research organisation, who recently created a global database of ships that have been deliberately wrecked to create artificial reefs. “There is the potential to attract a lot of fish, molluscs, different seaweeds.”

Alamy

AlamyCleaning up an oil tanker is an expensive business, though – it can cost several million dollars to mop up all the toxic mess that accumulates in these vessels. But since 1985, 39 tankers of various sorts have been sunk off the coast of the US and one off the coast of Malta. Unfortunately, little work has been done to monitor the impact these vessels have had on the ocean environments where they were sunk.

Anecdotal reports from divers who have visited some of these tankers, however, suggests they host a rich diversity of life including lobsters, shellfish, barracuda and sharks. The wreck of the supertanker MT Haven, which sank off the coast of Genoa, Italy after an explosion on board in 1991 has also become a popular diver site. Although 40,000 tons of oil poured into the sea in the accident, it has since become home to a wide array of marine animals.

“It is surprising that so many of these ships have been deliberately sunk to provide habitats for fish,” says Conde. “But we need to start monitoring these sites properly. With the crisis we are facing in our oceans and climate, it would be good if there was a way of using ships like oil tankers to do some good.”

* The original version of this article incorrectly stated that operational oil tankers held enough oil for the world's cars to drive 3 billion miles. That figure has been corrected to 3 trillion miles.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.