'Out of sync': The trillion-dollar climate puzzle that's become a diplomatic nightmare

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs countries negotiate a new global goal to raise climate cash, these five charts show why discussions are so fraught.

A hundred billion dollars. It's a staggering amount of money, although there are in fact now 16 individuals with personal assets worth more than this amount. But at the ongoing UN climate talks it's also a highly loaded figure, especially for countries on the frontlines of climate change.

It's the threshold amount that, back during turbulent negotiations in 2009, rich countries promised to "mobilise" each year by 2020 to help the billions of people in developing countries transition to a greener economy and cope with the impacts of climate change.

This may sound like a lot, but it is already considered too little. The new number that's being floated by many developing countries: at least a trillion.

Climate negotiators at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, are discussing the details of how much money rich countries should provide to poor countries to help them mitigate emissions and cope with climate impacts. What they haven't decided yet is how much it will be – or many of the other details, such as the target date to deliver the money and who will contribute. A huge range of options have been put forward by different groups and countries.

The question is ultimately one of justice, those countries say. Richer nations have, after all, historically caused the lion's share of climate change. Poorer nations not only have less means to make costly climate adaptations, but the problem of climate change was also largely not of their making. (Read more about the world's fight for climate justice).

Climate finance is "not charity", Ani Dasgupta, president of the World Resources Institute, a non-profit based in Washington DC, told a press briefing ahead of COP29. It is needed for the world to be "in a better place," he said, adding: "Developing countries cannot meet their transition goals if there is no finance."

As talks continue in Baku, here are five key charts to help put the fraught discussions into context – and show what is really at stake.

What's been paid so far?

Money is a tough topic that has caused a lot of tension at climate talks for decades now, even as climate costs around the world continue to rise.

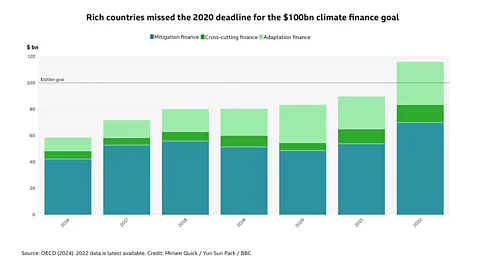

Rich countries failed to meet their promised 2020 deadline for the $100bn goal, only reaching the yearly goal for the first time two years later in 2022, as the chart below using figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows.

Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park / BBC

Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park / BBCThese countries have also been criticised for how they are delivering the money: for example, they are primarily providing money in the form of low-interest loans, that have to be repaid, rather than grants, which don't. Countries have also reclassified existing development aid rather than contributing fresh funding, according to a report by the climate news site Carbon Brief. Analysis by other organisations and researchers say the amount transferred is actually far lower than the OECD figures, meaning the $100bn goal still hasn't been met.

Speaking at COP29, UN climate chief Antonio Guterres said "now more than ever" finance promises must be kept. "Developing countries eager to act [on climate change] are facing many obstacles: scant public finance; raging cost of capital; crushing climate disasters; and debt servicing that soaks up funds," he said. "We need a new finance goal that meets the moment."

If the new climate finance goal fails, we will all feel the impact, says Charlene Watson, senior research associate at Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a global think tank based in London, UK. "It [would be] a global failure. We are all not reaching the global 1.5C target." (Read more about why 1.5C is a critical threshold for the climate).

Why do we need a new finance goal?

The focus on climate finance is coming now because back in 2015, countries at the COP21 talks in Paris agreed to set a new collective goal for it before 2025.

The $100bn goal, which was announced 15 years ago at a previous conference, COP15, is "now clearly out of sync with the total needs" of developing countries, says Joe Thwaites, senior advocate in international climate finance at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a US non-profit.

The only conditions fully agreed so far for the new goal are that it will be "from a floor of $100bn per year" and "take into account the needs and priorities of developing countries".

The original $100bn goal, in contrast, was a political number, says Watson. "It wasn't a number that was based on developing country needs. The [new goal] is supposed to be based on those needs. And those needs are just tremendous."

What's actually needed?

It's hard to say exactly what reducing emissions and coping with climate impacts has already cost developing countries or will cost in the future. This has led to a huge range of estimates of the money that is needed via the new goal.

Scientific understanding of these needs has come on "leaps and bounds" in recent years but is still challenging, "particularly as we've got so many moving pieces", says Thwaites. "The cost of [green] technology is going down in many cases, but on the other hand, climate impacts are increasing far faster than we were necessarily expecting. So it's very complicated to model these things out."

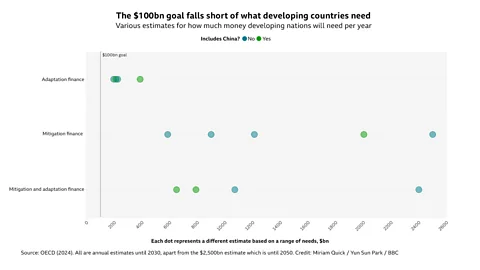

The chart below shows the large range in estimates of annual climate finance needs in developing countries by 2030. Even though estimates of what's needed are "not perfect", adds Thwaites, "they do show that total needs are in the trillions of dollars per year".

Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park/ BBC

Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park/ BBCOne key estimate of needs comes from research by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) of developing countries' national climate plans. It found that, in total, these countries have said they need $502bn (£394bn) specifically from developed countries each year until 2030.

Their total financial needs, however, amounted to more than 10 times this value at $5.8-5.9tn (£4.5-4.6tn), and it's not clear where most of the remaining money would come from. Many countries also didn't account for all the costs of climate change, such as the irreversible losses and damages caused by climate-related disasters, which is not covered by the $100bn goal but developing countries are calling for the new goal to include this.

These values may also change when countries update their national climate plans by early 2025. On the other hand, a stronger new climate finance goal at COP29 could lead to stronger national climate plans from poorer countries.

Ahead of the current talks, some developing countries and groups of developing countries put "very big numbers on the table", says Watson. "They want the goal to look like a trillion [dollars per year]," she says. "Developed countries haven't yet officially put a quantum on the table, so we don't know how much bigger than $100bn it's going to be."

An expert group of economists established by the COP26 and COP27 presidencies has similarly recommended that rich countries spend $1tn (£785bn) annually by 2030 on climate and nature investments in developing countries, out of $2.4tn (£1.88tn) in total needs in these countries.

But this calculation does not take into account China's financial needs. China is considered to be a developing country in the UN climate process, this makes the economists' calculation "a difficult number to try and use in a [final COP] decision", says Thwaites.

How $100bn compares to fossil fuel earnings

It's often pointed out that $100bn is a drop in the ocean compared with the money flowing through financial markets around the world.

Notably, revenues in the oil and gas industry have averaged close to $3.5tn (£2.75tn) per year since 2018.

Oil and gas earnings soared from 2022 due to the surging price of oil and gas following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2023, the world's largest five fossil fuel companies paid their shareholders $111bn (£87.4bn), according to analysis by Global Witness, a non-profit with offices in London and Washington DC. BP and Shell both reported their second highest annual profit in a decade in 2023, a total of $13.8bn (£11bn) and $28.2bn (£22.3bn) respectively.

Fossil fuel companies' revenues, combined with soaring coal, oil and gas emissions, have led some groups to suggest sourcing climate finance directly from the fossil fuel sector.

One proposal, backed by several climate vulnerable nations and a range of non-profits, is for polluters to pay an international tax on fossil fuel extraction, which they say would also encourage the phase out of fossil fuels. An analysis by campaign group Stamp Out Poverty found this "climate damages tax" could raise $720bn (£565bn) by 2030 to help the world's poorest countries with climate damages.

Another proposal is to tax the windfall profits of fossil fuel companies that benefit from high energy prices.

However, fossil fuel taxes could only fund climate losses and damages temporarily as governments have agreed to transition away from coal, oil and gas. (Read more about what the world would look like if polluters footed the climate bill.)

Other suggestions for raising climate cash include a G20 wealth tax, a shipping emissions tax or even a frequent flier levy.

How the $100bn compares to climate damage

Climate change is already causing huge financial losses around the world. One 2023 paper found that the global costs of extreme weather attributable to climate change was an average of $143bn (£113bn) per year between 2000 and 2019. (Read more about how climate change is rewriting the rules of extreme storms.)

Developing countries are often especially hard hit. While overall financial losses tend to be greater in richer countries, poorer countries see higher shares of GDP loss. These countries also suffer the most in terms of lives lost and disrupted.

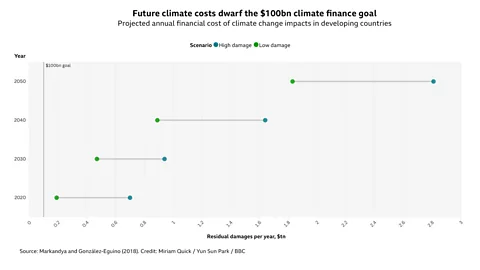

Such losses are only set to get worse. A 2018 paper found that the loss and damage due to climate change in developing countries will reach $290-580bn (£228-456bn) in 2005 money by 2030, equivalent to $468-936bn (£368-737bn) today. These damages could more than triple by 2050, it found.

Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park / BBC

Miriam Quick/ Yun Sun Park / BBCDamage to farming, infrastructure, productivity and health around the world will cost $38tn (£30bn) per year by 2050, according to analysis by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. Climate change has already committed the world economy to an income reduction of 19% up to 2050, the researchers concluded.

A Marshall plan for the climate?

The unprecedented scale of the climate challenge has led some to call for a green Marshall plan. The idea refers to the US programme to help fund Europe's recovery after World War Two. The US forked out $13.6bn (£10.7bn) in 1948 in economic aid, equivalent to around 5% of its GDP at the time.

"I have some sympathy with analogies of the Marshall plan," says Thwaites. "It is a helpful framing in the sense that is shows that human societies are able to organise themselves and mobilise massive amounts of resources".

However, the Marshall plan only covered a few years, while most people see the climate finance effort as needing to go "probably to mid-century", Thwaites says.

One of the biggest debates over the last few years has been who is going to contribute to the new fund, says Watson. The previous $100bn goal was agreed to by 23 developed countries and the EU, and notably didn't include China, now the world's largest polluter.

Many developed countries think some of the increasingly wealthy developing nations should be contributing to the new finance goal. "[They] want to see very specific provisions for who needs to contribute," says Watson. It's worth noting that many developing countries, including China, already provide some international climate finance, but that this is currently not counted towards the climate finance goal.

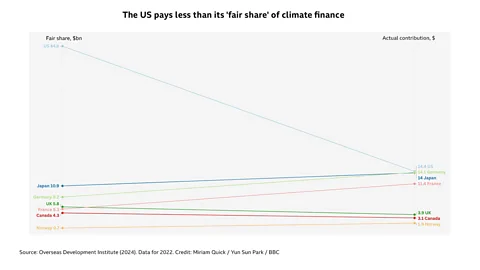

There is mounting frustration among developing countries that the world's biggest emitters have not paid their fair share of climate finance to date. ODI has estimated countries' fair share, based on their historical responsibility for cumulative emissions, GDP and population.

Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park/ BBC

Miriam Quick / Yun Sun Park/ BBCBig emitters' failure to pay their fair share has led to "a lot of anger and frustration and a lack of trust and confidence", says Sarah Colenbrander, director of the climate and sustainability programme at ODI.

The US, for example, paid just $14bn (£11bn) in climate finance in 2022, less than a third of its fair share of $45bn (£36bn). In 2021, the country provided $9bn (£7bn) of its $44bn (£35bn) fair share, according to ODI analysis.

"America just repeatedly fails to deliver," says Watson. Climate experts also now see a Trump presidency as a major setback for global climate action and a huge roadblock to raising critical funds for climate vulnerable countries.

Even without US leadership, though, debates on finance will continue to be a huge focus in Baku and future climate talks.

"In the future, all COPs will be about finance," says Dasgupta. "That is where we need to come to an agreement and where the question of justice looms largest."

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.