A frozen graveyard: The sad tales of Antarctica’s deaths

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBeneath layers of snow and ice on the world’s coldest continent, there may be hundreds of people buried forever. Martha Henriques investigates their stories.

BBC Future has brought you in-depth and rigorous stories to help you navigate the current pandemic, but we know that’s not all you want to read. So now we’re dedicating a series to help you escape. We’ll be revisiting our most popular features from the last three years in our Lockdown Longreads.

You’ll find everything from the story about the world’s greatest space mission to the truth about whether our cats really love us, the epic hunt to bring illegal fishermen to justice and the small team which brings long-buried World War Two tanks back to life. What you won’t find is any reference to, well, you-know-what. Enjoy.

In the bleak, almost pristine land at the edge of the world, there are the frozen remains of human bodies – and each one tells a story of humanity’s relationship with this inhospitable continent.

Even with all our technology and knowledge of the dangers of Antarctica, it can remain deadly for anyone who goes there. Inland, temperatures can plummet to nearly -90C (-130F). In some places, winds can reach 200mph (322km/h). And the weather is not the only risk.

Many bodies of scientists and explorers who perished in this harsh place are beyond reach of retrieval. Some are discovered decades or more than a century later. But many that were lost will never be found, buried so deep in ice sheets or crevasses that they will never emerge – or they are headed out towards the sea within creeping glaciers and calving ice.

The stories behind these deaths range from unsolved mysteries to freak accidents. In the second of our new series Frozen Continent, BBC Future explored what these events reveal about life on the planet's most inhospitable landmass.

1800s: Mystery of the Chilean bones

At Livingston Island, among the South Shetlands off the Antarctic Peninsula, a human skull and femur have been lying near the shore for 175 years. They are the oldest human remains ever found in Antarctica.

The bones were discovered on the beach in the 1980s. Chilean researchers found that they belonged to a woman who died when she was about 21 years old. She was an indigenous person from southern Chile, 1,000km (620 miles) away.

Analysis of the bones suggested that she died between 1819 and 1825. The earlier end of that range would put her among the very first people to have been in Antarctica.

Yadvinder Malhi

Yadvinder MalhiThe question is, how did she get there? The traditional canoes of the indigenous Chileans couldn’t have supported her on such a long voyage through what can be incredibly rough seas.

“There’s no evidence for an independent Amerindian presence in the South Shetlands,” says Michael Pearson, an Antarctic heritage consultant and independent researcher. “It’s not a journey you’d make in a bark canoe.”

The original interpretation by the Chilean researchers was that she was an indigenous guide to the sealers travelling from the northern hemisphere to the Antarctic islands that had been newly discovered by William Smith in 1819. But women taking part in expeditions to the far south in those early days was virtually unheard of.

You might also like:

Sealers did have a close relationship with the indigenous people of southern Chile, says Melisa Salerno, an archaeologist of the Argentinean Scientific and Technical Research Council (Conicet). Sometimes they would exchange seal skins with each other. It’s not out of the question that they traded expertise and knowledge, too. But the two cultures’ interactions weren’t always friendly.

“Sometimes it was a violent situation,” says Salerno. “The sealers could just take a woman from one beach and later leave her far away on another.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA lack of surviving logs and journals from the early ships sailing south to Antarctica makes it even more difficult to trace this woman’s history.

Her story is unique among the early human presence in Antarctica. A woman who, by all the usual accounts, shouldn’t have been there – but somehow she was. Her bones mark the start of human activity on Antarctica, and the unavoidable loss of life that comes with trying to occupy this inhospitable continent.

29 March 1912: Scott’s South Pole expedition crew

Robert Falcon Scott’s team of British explorers reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, just three weeks after the Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had departed from the same spot.

The British group’s morale was crushed when they discovered that they had not arrived first. Soon after, things would get much worse.

Attaining the pole was a feat to test human endurance, and Scott had been under huge pressure. As well as dealing with the immediate challenges of the harsh climate and lack of natural resources like wood for building, he had a crew of more than 60 men to lead. More pressure came from the high hopes of his colleagues back home.

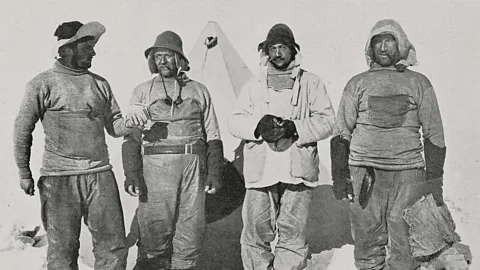

Herbert Ponting/Wikipedia

Herbert Ponting/Wikipedia“They mean to do or die – that is the spirit in which they are going to the Antarctic,” Leonard Darwin, a president of the Royal Geographical Society and son of Charles Darwin, said in a speech at the time.

“Captain Scott is going to prove once again that the manhood of the nation is not dead… the self-respect of the whole nation is certainly increased by such adventures as this,” he said.

Scott was not impervious to the expectations. “He was a very rounded, human character,” says Max Jones, a historian of heroism and polar exploration at the University of Manchester. “In his journals, you find he’s racked with doubts and anxieties about whether he’s up to the task and that makes him more appealing. He had failings and weaknesses too.”

Despite his worries and doubts, the mindset of “do or die” drove the team to take risks that might seem alien to us now.

On the team’s return from the pole, Edgar Evans died first, in February. Then Lawrence Oates. He had considered himself a burden, thinking the team could not return home with him holding them back. "I am just going outside and may be some time," he said on 17 March.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPerhaps he had not realised how close the rest of the group were to death. The bodies of Oates and Evans were never found, but Scott, Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers were discovered by a search party several months after their deaths. They had died on 29 March 1912, according to the date in Scott’s diary entry. The search party covered them with snow and left them where they lay.

“I do not think human beings ever came through such a month as we have come through,” Scott wrote in his diary’s final pages. The team knew they were within 18km (11 miles) of the last food depot, with the supplies that could have saved them. But they were confined to a tent for days, growing weaker, trapped by a fierce blizzard.

“They were prepared to risk their lives and they saw that as legitimate. You can view that as part of a mindset of imperial masculinity, tied up with enduring hardship and hostile environments,” says Jones. “I’m not saying that they had a death wish, but I think that they were willing to die.”

14 October 1965: Jeremy Bailey, David Wild and John Wilson

Four men were riding a Muskeg tractor and its sledges near the Heimefront Mountains, to the east of their base at Halley Research Station in East Antarctica, close to the Weddell Sea. The Muskeg was a heavy-duty vehicle designed to haul people and supplies over long distances on the ice. A team of dogs ran behind.

Three of the men were in the cab. The fourth, John Ross, sat behind on the sledge at the back, close to the huskies. Jeremy (Jerry) Bailey, a scientist measuring the depth of the ice beneath the tractor, was driving. He and David (Dai) Wild, a surveyor, and John Wilson, a doctor, were scanning the ice ahead. Snow obscured much of the small, flat windscreen. The group had been travelling all day, taking turns to warm up in the cab or sit out back on the sledge.

Ross was staring out at the vast ice, snow and Stella Group mountains. At about 8:30, the dogs alongside the sledge stopped running. The sledge had ground to a halt.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRoss, muffled with a balaclava and two anoraks, had heard nothing. He turned to see that the Muskeg was gone. Ahead, the first sledge was leaning down into the ice. Ross ran up to it to find it had wedged in the top of a large crevasse running directly across their course. The Muskeg itself had fallen about 30m (100ft) into the crevasse. Down below, its tracks were wedged vertically against one ice wall, and the cab had been flattened hard against the other.

Ross shouted down. There was no reply from the three men in the cab. After about 20 minutes of shouting, Ross heard a reply. The exchange, as he recorded it from memory soon after the event, was brief:

Ross: Dai?

Bailey: Dai’s dead. It’s me.

Ross: Is that John or Jerry?

Bailey: Jerry.

Ross: How is John?

Bailey: He’s a goner, mate.

Ross: What about yourself?

Bailey: I’m all smashed up.

Ross: Can you move about at all or tie a rope round yourself?

Bailey: I’m all smashed up.

Ross tried climbing down into the crevasse, but the descent was difficult. Bailey told him not to risk it, but Ross tried anyway. After several attempts, Bailey stopped responding to Ross’s calls. Ross heard a scream from the crevasse. After that, Bailey didn’t respond.

Crevasses – deep clefts in the ice stretching down hundreds of feet – are serious threats while travelling across the Antarctic. On 14 October 1965, there had been strong winds kicking up drifts and spreading snow far over the landscape, according to reports on the accident held at the British Antarctic Survey archives. This concealed the top of the chasms, and crucially, the thin blue line in the ice ahead of each drop that would have warned the men to stop.

“You can imagine – there’s a bit of drift about, and there’s bits of ice on the windscreen, your fingers are bloody cold, and you think it’s about time to stop anyway,” says Rod Rhys Jones, one of the expedition party who had not gone on that trip with the Muskeg. He points to the crevassed area the Muskeg had been driving over, on a map of the continent spread over his coffee table, littered with books on the Antarctic.

Getty Images

Getty Images“You’re driving along over the ice and thumping and bumping and banging. You don’t see the little blue line.”

Jones questions whether the team had been given adequate training for the hazards of travel in Antarctica. They were young men, mostly fresh out of university. Many of them had little experience in harsh physical conditions. Much of their time preparing for life in Antarctica was spent learning to use the scientific equipment they would need, not training them in how to avoid accidents on the ice.

Each accident in Antarctica has slowly led to changes in the way people travelled and were trained. Reports filed after the incident recommended several ways to make travel through crevassed regions safer, from adapting the vehicle, to new ways to hitch them together.

August 1982: Ambrose Morgan, Kevin Ockleton and John Coll

The three men set out over the ice for an expedition to a nearby island in the depths of the Antarctic winter.

The sea ice was firm, and they made it easily to Petermann Island. The southern aurora was visible in the sky, unusually bright and strong enough to wipe out communications. The team reached the island safely and camped out at a hut near the shore.

Soon after reaching the shore, a large storm blew in that, by the next day, entirely destroyed the sea ice. The group was stranded, but concern among the party was low. There was enough food in the hut to last three people more than a month.

In the next few days, the sea ice failed to reform as storms swept and disrupted the ice in the channel.

Richard Fisher

Richard FisherThere were no books or papers in the hut, and contact with the outside world was limited to scheduled radio transmissions to the base. Soon, it had been two weeks. The transmissions were kept brief, as the batteries in their radios were getting weaker and weaker. The team grew restless. Gentoo and Adelie penguins surrounded the hut. They might have looked endearing, but their smell soon began to bother the men.

Things got worse. The team got diarrhoea, as it turned out some of the food in the hut was much older than they had thought. The stench of the penguins didn’t make them feel any better. They killed and ate a few to boost their supplies.

The men waited with increasing frustration, complaining of boredom on their radio transmissions to base. On Friday 13 August 1982, they were seen through a telescope, waving back to the main base. Radio batteries were running low. The sea ice had reformed again, providing a tantalising hope for escape.

Two days later, on Sunday 15 August, the group didn’t check in on the radio at the scheduled time. Then another large storm blew in.

The men at the base climbed up to a high point where they could see the island. All the sea ice was gone again, taken out by the storm.

“These guys had done something which we all did – go out on a little trip to the island,” says Pete Salino, who had been on the main base at the time. The three men were never seen again.

There were very strong currents around the island. Reliable, thick ice formed relatively rarely, Salino recalls. The way they tested whether the ice would hold them was primitive – they would whack it with a wooden stick tipped with metal to see if it would smash.

Even after an extensive search, the bodies were never found. Salino suspects the men went out onto the ice when it reformed and either got stuck or weren’t able to turn back when the storm blew in.

“It does sound mad now, sitting in a cosy room in Surrey,” Salino says. “When we used to go out, there was always a risk of falling through, but you’d always go prepared. We’d always have spare clothing in a sealed bag. We all accepted the risk and felt that it could have been any of us.”

Legacy of death

For those who experience the loss of colleagues and friends in Antarctica, grieving can be uniquely difficult. When a friend disappears or a body cannot be recovered, the typical human rituals of death – a burial, a last goodbye – elude those left behind.

Clifford Shelley, a British geophysicist based at Argentine Islands off the Antarctic Peninsula in the late 1970s, lost friends who were climbing the nearby peak Mount Peary in 1976. It was thought that those men – Geoffrey Hargreaves, Michael Walker and Graham Whitfield – were trapped in an avalanche. Signs of their camp were found by an air search, but their bodies were never recovered.

Getty Images

Getty Images“You just wait and wait, but there’s nothing. Then you just sort of lose hope,” Shelley says.

Even when the body is recovered, the demanding nature of life and work on Antarctica can make it a hard place to grieve. Ron Pinder, a radio operator in the South Orkneys in the late 1950s and early 1960s, still mourns someone who slipped from a cliff on Signy Island while tagging birds in 1961. The body of his friend, Roger Filer, was found at the foot of a 20ft (6m) cliff below the nests where he was thought to have been tagging birds. His body was buried on the island.

“It is 57 years ago now. It is in the distant past. But it affects me more now than it did then. Life was such that you had to get on with it,” Pinder says.

The same rings true for Shelley. “I don’t think we did really process it,” he says. “It remains at the back of your mind. But it’s certainly a mixed feeling, because Antarctica is superbly beautiful, both during the winter and the summer. It’s the best place to be and we were doing the things we wanted to do.”

swancharlotte/wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0

swancharlotte/wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0These deaths have led to changes in how people work in Antarctica. As a result, the people there today can live more safely on this hazardous, isolated continent. Although terrible incidents still happen, much has been learned from earlier fatalities.

For the friends and families of the dead, there is an ongoing effort to make sure their lost loved ones are not forgotten. Outside the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK, two high curved oak pillars lean towards one another, gently touching at the top. It is half of a monument to the dead, erected by the British Antarctic Monument Trust, set up by Rod Rhys Jones and Brian Dorsett-Bailey, Jeremy’s brother, to recognise and honour those who died in Antarctica. The other half of the monument is a long slither of metal leaning slightly towards the sea at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, where many of the researchers set off for the last leg of their journey to Antarctica.

Viewed from one end so they align, the oak pillars curve away from each other, leaving a long tapering empty space between them. The shape of that void is perfectly filled by the tall steel shard mounted on a plinth on the other side of the world. It is a physical symbol that spans the hemispheres, connecting home with the vast and wild continent that drew these scientists away for the last time.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.