Do Brits really have bad teeth?

Sharon Dominick/iStock by Getty Images

Sharon Dominick/iStock by Getty ImagesBritons have poor dental health… or so goes the stereotype. Is that old adage as false as a set of dentures? Claudia Hammond investigates.

According to dozens of jokes, one spy-spoof movie series and even some Britons themselves, the British and bad teeth go as hand-in-hand as tea and crumpets. You can even tell when a British film star has been to Hollywood, the story goes, because they suddenly procure a bright white, perfectly aligned smile.

There’s been no shortage of opinions about the issue in recent weeks. The doctor Chris van Tulleken, who is presenting a BBC TV show about teeth, told the Radio Times that having “brown, foul teeth doesn't really bother [Britons]”. And as BBC Magazine discovered when they reviewed the state of British teeth last week, some UK-based dentists say that their customers prefer a more “natural look” than their American counterparts.

Yet what does the data say? First, it depends on what you mean by “bad.” Whether you choose to whiten or straighten your teeth is a matter of fashion. In terms of dental health, what really matters is decay. On that measure, Britain does better than many other countries around the world – including the United States.

In a recent World Health Organisation report of the dental status of children known as the DFMT index, for example, British youths had fewer decayed, missing or filled teeth than those in France, Spain and Sweden; Britain’s rates were comparable with Germany, the Netherlands and Finland.

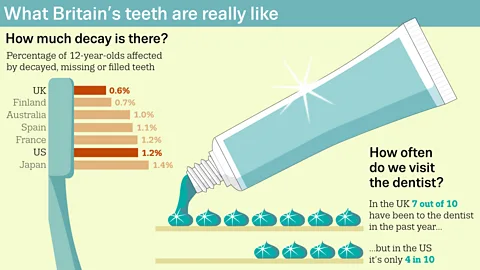

Nigel Hawtin

Nigel HawtinThe United States, on the other hand, did quite a bit worse. At the age of 12, children in the United Kingdom have on average better teeth than their American counterparts. This is due to a decrease in the number of children with decayed teeth in Britain in the last 10 years. In England there are, on average, 0.6 decayed missing or filled teeth per 12-year-old. In the United States, the figure is double this… but the US data was collected a few years earlier than the British data.

Another way of approaching the issue is to look at how often people visit the dentist. In 2012, seven out of 10 people in Britain visited the dentist, compared with four in 10 Americans. In a league of 16 industrialised countries, the UK came in third; the US came in 13th. (The country with the most dental visits was France, but the data for France indicated whether people had visited the dentist during the previous two years, rather than one, which might have raised the figures).

The problem with this kind of information, though, is that it doesn’t tell you why people visited the dentist. Did they visit because they were conscientious in caring for their teeth – or because their teeth were in such a terrible state that they had problems with them?

Rpsycho/iStock by Getty Images

Rpsycho/iStock by Getty ImagesEven attending a preventative check-up every six months is not necessarily a sign of good dental health, as there is a long-running debate over whether these visits are associated with more, rather than less, dental disease; as I’ve discussed previously, some experts believe that adults without problems should not visit this frequently. A Cochrane review, which gathers and assesses the most trustworthy data from around the world, concluded that there was not enough evidence to recommend or refute the idea that check-ups are needed every six months.

But over the years some of the international comparisons have been challenged. In 2000, Australia, for example, came 21st out of 28 industrialised countries in a table of figures for tooth loss, known as ‘endentulism’. These figures were influential enough to inform dental health policy in the country – but the actual data was collected as far back at 1987.

In a newer analysis that used data gathered in Australia in 2003-04, a team compared Australia with Germany, Britain and the United States. This time Australia fared better, partly because the oldest generation of people – whose teeth had been removed years ago, when it wasn’t such an uncommon practice – had now died, making the overall figures look very different. In this research, the UK didn’t come out so well… but this time, the data for Australia was much newer, while the UK data was from five years earlier than the Australian data – and a whole decade before the paper was published.

Les Lee/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Les Lee/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe overall lesson: since dental health trends are changing quickly, generally for the better, comparisons between countries are difficult to do accurately, as the exact year when you collect the data makes a big difference.

Whether you’re looking at missing teeth, decayed teeth or dental visits, it’s not the case that the British today have particularly bad teeth. But that doesn’t mean that Britain – or any other industrialised nation – doesn’t have cause for concern.

What is far more important than which country you are from is where exactly you are within it. In Canada, for example, the rate of tooth loss is six times higher in low-income families compared to their wealthier counterparts. And in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, data published this year show that dental problems vary widely by socioeconomic status: just 2% of three-year-olds in the more affluent area of south Gloucestershire, for example, have tooth decay, compared with 34% in Leicester. The reasons for the regional differences include socioeconomic status, access to a dentist and whether there is fluoride in the water. Last year, a study found that the richest 20% of adults over 65 years old in Britain had on average eight fewer teeth than the poorest 20%.

The British, it seems, don’t need to worry about their teeth being bad – at least compared with Americans. Instead, we need to ask why some children are destined to have much worse teeth than others… even within the same country.