Is e-waste an untapped treasure?

Your old phone or electric toothbrush could end up as a part in a 3D printer or piece of artwork, says Jonathan Kalan.

In a hall of the Africa Innovation Summit in Cape Verde, the smell of melting plastic permeated the air. A crowd had gathered around a small stand to watch a special kind of machine go to work.

Controlling the device were members of WoeLab, a community “maker space” based in Togo, West Africa. Over the space of an hour, their creation gradually built a small plastic toy, layer by layer. It looked and performed like a typical 3D printer – but this one was different. Why? It was made almost entirely from electronic waste and scraps.

The demonstration in Cape Verde clearly impressed the audience – the Woelab team won the award for “best innovation” of the exhibition.

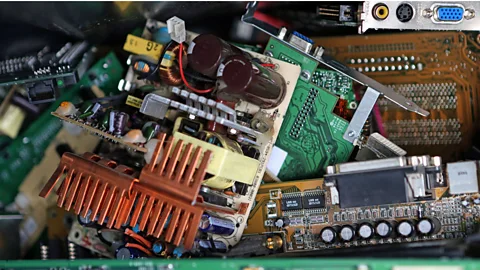

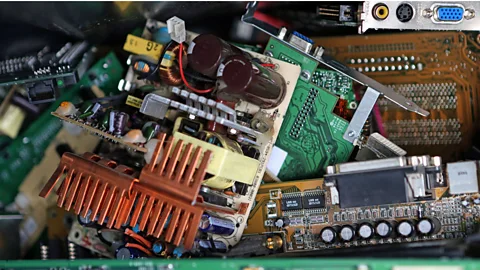

Electronic waste, or e-waste, is a rapidly growing global problem. As our desire for personal gadgets grows, we end up with more and more electronics in incinerators or landfills, potentially seeping toxic substances like lead and mercury into groundwater.

Yet many are realising that the gadgets we chuck away can be ripped apart and transformed into something new – brand new technology, or even art. Your old phone, printer or electric toothbrush may seem worthless, but to these MacGyver-style makers, it’s a building material.

In 2012, we discarded 48.9 million tonnes of electrical and electronic products. If current trends continue, by 2017, the annual amount of e-waste produced globally will reach 65.4 million tonnes – that’s roughly 20% of the weight of all the people living on Earth.

“The e-waste issue has exploded, and will continue to explode because of increased production of electronic equipment – anything with a battery or a plug – and because of the enormous hunger of consumption of this equipment around the world”, says Ruediger Kuehr,executive secretary of the Step Initiative, a United Nations University programme aiming to tackle e-waste.

Step recently produced the first “e-waste world-map”, showing how much e-waste each country produces. At 11.1 million tonnes, China was the leading producer in 2012, followed by the US at 10 million tonnes.

In developed countries, one of the bigger problems is consumer awareness – people discarding their e-junk in regular bins instead of taking it to be recycled. Yet in developing countries such facilities just don’t exist, says Kuerh. By 2017, the total number of obsolete PCs and phones in developing regions will exceed that of developed regions.

One man’s waste, however, is another man’s treasure. “There might be advanced circuit boards in this equipment – especially in the newer equipment,” explains Kuerh.

That’s what drew the team at WoeLab in Togo to use e-waste to build new technology. The group – a team of around 20 people including students, tailors and engineers – has always been interested in hacking and building things. And when they saw a Prusa Mendel, a popular self-build 3D printer kit in the US and Europe, they decided to try and build their own.

“In the beginning, the idea was not to recycle, but to create something great out of local material, a high-low tech thing,” explains Djemaah Allahar of WoeLab. “We know Africa is a continent where all the e-waste of Europe and so-on is thrown. Why not create a 3D printer with the recycled materials we have?”

Using parts and wires from old computers, scanners and photocopiers (some of it for free, but most bought), and an Arduino electronics card as the brain, they managed to put together a working prototype for a few hundred euros (see below). Now they’re seeking to commercialise the printer.

Their success got them – and others – thinking about what else could be made with e-waste. With the help of an open-source project from France called Jerry DIT, another team at WoeLab has built four working computers they call “W.Jies”, made out of old servers and computer components. They are mounted inside jerry cans.

“In Togo, there are many people who can’t have access to computers, because they don’t have money to buy a new computer,” says Allahare. “But we have many computers that are broken and not working. It’s sometimes just a little piece that is spoiled in it. W.Jies can help people get connected, get information, and help kids learn ICT from low-cost computers.” They are hoping to sell their jerry can computers for around $100 each.

Others are using e-waste to build phones. FairPhone, a company that makes phones from recycled components and conflict-free minerals, is hoping to turn one of Ghana’s biggest “digital dumping grounds”, a place called Agbogbloshie, into a source of parts. A lot of repair shops, too, have old unwanted phones that they can now sell instead of throwing away, according to Fairphone’s Bibi Bleekemolen.

Then there are those turning e-waste into beautiful creations. In Kenya, Alex Matizo, a 19-year-old entrepreneur recently founded E-Lab, a startup that aims to tackle African e-waste by transforming it into art, fashion, jewellery and more.

A computer science student at the University of Nairobi with a passion for the arts, Matizo was inspired after seeing the dumping of e-waste near his home in Athi River, on the outskirts of the capital.

Matizo has already created various pieces of jewellery, artworks and notebooks out of circuit boards, and eventually hopes to build a network of entrepreneurs to collect and repurpose e-waste on a larger scale.

To really make a dent in the developing world’s e-waste problem, however, these entrepreneurs can’t do it alone. The volume of e-waste flowing into Africa and elsewhere is too great.

“The norm is that globally, e-waste is being swept from north to south, to areas lacking in the proper infrastructure and technologies to deal with it,” explains Jim Puckett, executive director of Basel Action Network, an organisation aiming to tackle global toxic waste. “It gets a second use in the developing country perhaps, but then still ends up in informal wayside dumps.”

Kuehr agrees. “What is lacking is infrastructure to properly treat hazardous or scarce components, because it requires large industrial processes – smelters, for example,” he says.

In the meantime, however, much of the problem will be left in the hands of those dreaming up clever ways to re-use old gadgets and electronics. Building new tech and artworks certainly won’t get rid of e-waste entirely – but it can help. And for a group like Woelab, they get the kudos of being one of the first groups in the world to build a working 3D printer from a pile of junk.

If you would like to comment on this, or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook or Google+ page, or message us on Twitter.