Africa, Clooney and an unlikely space race

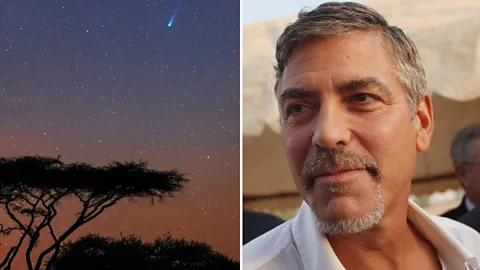

Plans to launch an African space agency are underway, and as Jonathan Kalan discovers, the indirect involvement of George Clooney in the continent's ambitious goals provides an unusual twist.

What do George Clooney and Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir have in common? They both have their eyes on space – and in particular, harnessing the satellites orbiting above Africa’s skies.

The pair join various governments and companies now looking to harness space research across the African continent. Although only a handful of countries – such as South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, and Morocco – currently have space programmes of their own, others are racing to catch up, including Ghana and Ethiopia.

An ambitious plan is now underway to build an African Space Agency called “AfriSpace”. And while Clooney’s contribution to all this may only be a cameo role, it’s still an important one. So what’s driving Africa’s soaring ambitions for space? And are the plans realistic?

Africa’s interest in space arguably began half a century ago, as the US and Soviet Union’s space race was heating up. In 1964, a Zambian science teacher named Edward Mukaka Nkoloso appointed himself the director of the Zambia National Academy of Space Research, and unofficially launched the first – and most eccentric – space programme on the continent. His rather lofty goal was to put a Zambian on the moon before anybody else. He would stage zero-gravity simulation training by sticking aspiring astronauts into a steel barrel and rolling them down a hill.

While it may be no surprise that Nkoloso’s plans failed to lift off, Africa’s space industry began to grow, albeit mostly with the help of more developed nations.

In the 1960s, Nasa built one of their Deep Space Network stations in Hartebeesthoek, South Africa, which supported several early robotic missions to the moon during the Apollo programme. In the following decades, South Africa developed its own space research projects, mostly for military purposes.

In 1970, on behalf of Nasa and with the help of Italian engineers, Kenya launched Uhuru – Swahili for “freedom” – the world’s first satellite dedicated to celestial X-ray astronomy, from a converted oil platform off its coast.

Taking off

Then, at the turn of the century, African nations began to ramp up their space efforts. In 2001 Nigeria established its National Space Research and Development Agency and launched its first small satellite in 2003. The satellites it put into the space provide everything from high-resolution imagery to monitor the country’s shrinking farmland, to cheaper wireless and internet coverage.

Last year, Ghana launched its Space Science and Technology Center, to “foster teaching, learning, commercial application of space research,” as a precursor to a full-blown space agency by 2016, intended to lead the nation’s civilian space exploration efforts. And Ethiopia – one of the world’s poorest countries – has unveiled two new telescopes atop a mountain on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, costing around $1.2 million each.

To Western eyes, it may seem rather innappropriate to launch space programmes in sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly 70% of the population still lives on less $2 a day. Yet Joseph Akinyede, director of the African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Nigeria, an education centre affiliated with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, says that the application of space science technology and research to “basic necessities” of life – health, education, energy, food security, environmental management – is critical for the development of the continent.

Much of Africa’s recent growth can be linked indirectly to space research. In particular, satellite technology has played a role in everything from telecommunications, broadcasting and GPS mapping to weather forecasting for agriculture and climate monitoring.

Since 2010, satellite capacity across the continent has nearly tripled, helping in part fuel Africa’s “mobile revolution”. Over 70% of Africans have mobile phones, according to a recent report from McKinsey, a global consulting firm – and satellites have often made it easier to connect remote areas, and hold future promise for cheaper satellite-based mobile broadband. Satellite mapping has also been used to discover the continents’ vast mineral reserves, and recently helped uncover an enormous underground water aquifer in Kenya’s driest region.

To get the most from all this technology on offer, Terefa Waluwa, chairman of the Ethiopian Space Science Society argues that enhancing local expertise via space research is vital. “It’s not to discover the universe again, or re-invent what is already known, but to learn it properly,” he explains. “Almost every sector here in Ethiopia is using space science technology”, he says, citing mobile phones, agricultural activities, and aviation. “If we want to use the applications, we need to know the hard part of science.”

Going it alone

Today, many African nations seem to be weaning off their reliance on the US, Europe and China. Nearly all of Africa’s space programmes are partnered with foreign countries – arguably limiting their autonomy and control of data and information generated. When it comes to what happens over Africa’s skies, “the third world is employing the institutions of the developed world,” argues Waluwa, “and we are paying highly for that.” The cost of investing in satellite technology may expensive, but the long term cost of purchasing satellite services from external providers can be even more so.

In light of this, calls are growing from many on the continent – and even the African Union – for the formation of AfriSpace, a pan-African space agency. One of the more vocal proponents is Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir, who rather surprisingly, appears to be partly motivated by his dissatisfaction about a project funded by the actor George Clooney.

With the money earned from his appearance in commercials for the coffee company Nespresso, Clooney has been funding the Satellite Sentinel Project (SSP), which he co-founded in 2010, to monitor the military activities of al-Bashir – who is accused of war crimes by the International Criminal Court. A satellite captures real-time imagery of Sudan, enabling a team of analysts to monitor troop movements, bombings and other aggressive activities by al-Bashir in the disputed border areas between Sudan and newly formed South Sudan.

“We’re trying to prevent deniability,” explains Akshaya Kumar, a lawyer who works with SSP. “We can see craters consistent with aerial bombardment…we can identify different types of buildings that have been destroyed – schools, medical clinics – and sound the alarm to stop violence from reaching certain levels of severity.”

President al-Bashir has indicated that this eye from above is rather unfair, a one-sided measurement of accountability, and so wants more African satellites up there too. Last year, al-Bashir called on attendees at the 4th African Union Conference for Ministers in charge of Communications and Information Technologies “to liberate Africa from the technological domination” and establish the AfriSpace space agency.

As it happens, several other African Union ministers already supported the idea of an African space agency, says Abdul Hakim Elwaer, director of Human Resources, Science and Technology for the African Union. An AU working group on space, chaired by South Africa, with members representing Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Egypt and Algeria, will present their recommendations on how to make AfriSpace a reality to an AU parliament in November next year.

Is an African space agency really achievable though? The African Union has historically struggled to achieve unity and consensus on the continent on a host of issues. Many politicians may baulk when they see what the plans actually cost. For years, African leaders have seen space investment as “a luxury, at the bottom of the list of priorities,” says Hakim. And some politicians may see a paradox in joining together their efforts: if one of the primary drivers of developing national space agencies in Africa is about sovereignty, working together may appear to be counter-productive.

The expertise required to rival other large space agencies may also be a long way off – at least judging by the way some existing African space organizations present themselves to the world. While researching this story, I found that nearly every national space agency or society website was loaded with incomplete or broken content – some were not even functioning. On one call to Ethiopia’s former Minister of Capacity Building, I received a pre-programmed error message. “The network is fizzing out. Please try again later,” it said. When I finally reached him, he told me “this is a good example for what I told you. Our use of space of technology is not to its full potential.”

Still, there is no doubt that activity is ramping up across the continent, and many remain positive that the dream of a pan-African space agency can be achieved.

“We know building independent African facilities will not happen overnight,” says Hakim. Yet he is hopeful. “See you in space,” he said, before ending the call, “… one day”.

If you would like to comment on this or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

or message us on .