How one surprising photo of a teenage Kate Moss kick-started the 1990s

Estate of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman Images

Estate of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman ImagesAn iconic image of Kate Moss marked an explosive moment of change in Britain – and helped to create the culture we now live in. It's among the photographs displayed in a new exhibition that celebrates the photography of The Face magazine.

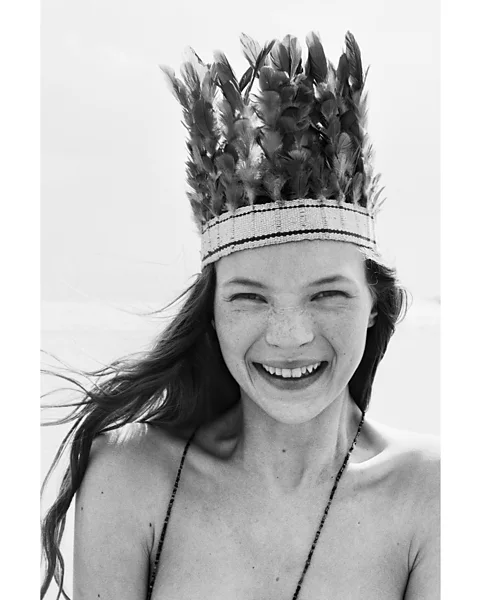

Freckled and fresh-faced, a 16-year-old Kate Moss laughs, make-up-free and unadorned except for a delicate string of beads and a headdress made of feathers – the image on the cover of The Face magazine in July 1990 was perfectly timed. It captured a moment in Britain when the nation's youth was coalescing around a burgeoning acid-house movement, with impromptu parties filling disused warehouses, aircraft hangars and fields across the country. The escapist, chaotic rave scene that spanned class and race was an explosion of optimism and euphoria amid difficult times of high unemployment and a weak economy. The magazine's cover portrait marked a new era, with Kate Moss the coming decade's feather-crowned queen.

The iconic portrait by Corinne Day is among the photographs on display at London's National Portrait Gallery in the exhibition The Face Magazine: Culture Shift. Lee Swillingham, former art director of The Face – along with photographer Norbert Schoerner – came up with the idea for the show, which charts the British style magazine's photography through the years. "For me, The Face really was the best chronicler of British youth culture," says Swillingham, who co-curated the exhibition with NPG's senior curator of photographs, Sabina Jaskot-Gill.

The Moss portrait was "a breath of fresh air," Swillingham tells the BBC. "It was a moment of moving on from the aspirational, stylised glamour of the 80s, and into a more pared-down and realistic phase in fashion terms. That whole photography style went hand in hand with a more attainable sense of beauty."

Estate of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman Images

Estate of Corinne Day/ Bridgeman ImagesIt was Swillingham's predecessor as art director Phil Bicker who initially championed the emerging photographer Corinne Day and the then unknown teenage model Kate Moss. "I was searching for someone who would be 'the face of The Face'," Bicker tells the BBC – not a glossy, "aspirational" fashion muse but a natural, real one, in tune with the magazine's readership. "Kate had the Britishness and youthfulness that The Face represented – she was funny, and laughed a lot. She seemed to me a person first, and a model second." Inside the July 1990 issue of the magazine, Moss is shown on the beach at Camber Sands on the south coast of England, messing about guilelessly in a series of photos striking in their simplicity and naturalness.

It was "a perfect storm," says Bicker. "And despite Kate's subsequent global profile and extensive career, she's still associated with The Face, and that defining moment which launched her career. It was shot in a way by Corinne that allowed Kate’s personality and positive energy to come through, so that when people saw the images, they forgot they were looking at a styled fashion story, instead believing this was a portrait of Kate unadorned."

Moss nor her agency particularly liked this raw, slightly gawkish depiction of the model, according to Sheryl Garratt, then The Face editor, writing in The Observer in 2000. The shoot has nonetheless remained a cultural touchstone, embodying a moment in time. The magazine's founder Nick Logan later said: "At that time, at the start of the rave scene, I remember saying, 'let's aim it at those people dancing in fields'." The 1990 images of Moss reflected not only a new aesthetic but also a deeper cultural change in the UK, with the cover line of the magazine referring to a "summer of love", in reference to the exploding outdoor rave scene.

More like this:

• Eight striking images that define America

"It was a real moment of transition," Angela McRobbie, professor of cultural studies at Goldsmiths, University of London, tells the BBC. "It marked a shift, when a subculture moved into mass visibility. Rave culture opened its doors to a much vaster section of boys and girls who would never have gone dancing in that way before. It was a new form of leisure, and a youth culture becoming mass leisure."

Whereas the post-punk music-and-fashion scene had emanated more from an "art-school" milieu, argues McRobbie, the rave scene at its height was a much broader movement that grew organically from economic and social circumstances. "The working-class rave scene was an escape from the mundanity of post-industrial Britain, where the skilled labour market had declined. Rave gave working-class kids a sense of freedom," she says.

It was a sense of empowerment, McRobbie continues, which was later echoed in Morvern Callar, the 2002 film by Scottish director Lynne Ramsay, which starred Samantha Morton. "It's based on a book by Alan Warner," says McRobbie, "and it's about working-class girls in Aberdeen, stacking shelves". It charts a gradual awakening of the protagonist's sense of agency and self, and – like Day's image of Moss on the beach – emanates a mood of escape, freedom in nature, and a sense of possibility.

Glen Luchford

Glen Luchford"The rave scene was a gamechanger in terms of gender," says McRobbie, whose book Feminism, Young Women and Cultural Studies traces the evolution of British subcultures from the 1970s. "For boys, it was a new moment of emotional, non-aggressive sexuality, partly because of the [drug] ecstasy, and the expression of feelings of love and joy, and dancing for five to seven hours non-stop, which boys would have done before in gay or queer spaces like Heaven in London. But for your average working-class boy to enjoy that physical pleasure, openness and freedom, that was new. And for girls it was a time of getting in touch with their physical bodies, too, dancing for hours."

But despite the "summer of love" headline on The Face's 1990 cover, according to McRobbie, this cultural moment in the UK had nothing much in common with the original 1960s Summer of Love in the US. "Sociologists wouldn't put those two movements together," she says – the hippy Summer of Love in San Francisco in 1967 was "qualitatively different". "[The rave scene] was not connected to an overtly political agenda. The San Francisco Summer of Love was a time of social change that grew from Berkeley University and was pro-civil rights. It was overtly political and, with [Allen] Ginsberg involved, literary."

Young style rebels

If there was a precursor of the British rave movement, it was the Swinging '60s, which were imbued with a mood of liberation and the breaking down of past hierarchies. "The Swinging '60s were associated with a freeing up and a breaking down of barriers, in class, sexuality and gender," says McRobbie. "It was designer Mary Quant [creator of the mini skirt], the Pill. Doors were opening, and for working-class young women it was an important time of excitement and freedom, particularly in urban centres such as London and Glasgow."

The It girl of that moment was the gamine, teenage model Twiggy – with her waifish figure, cheeky smile and working-class origins. Bicker told The Observer: "Kate hadn't been modelling for very long but, even in her awkwardness, she had that thing about her that Twiggy had in the 60s, a freshness that matched the times." She was, in the way she defined her era, Moss's predecessor – along with the late Marianne Faithfull, the "wide-eyed poster girl for the Swinging '60s", who later in life became good friends with the model.

Inez & Vinoodh/ courtesy of the Ravestijn Gallery

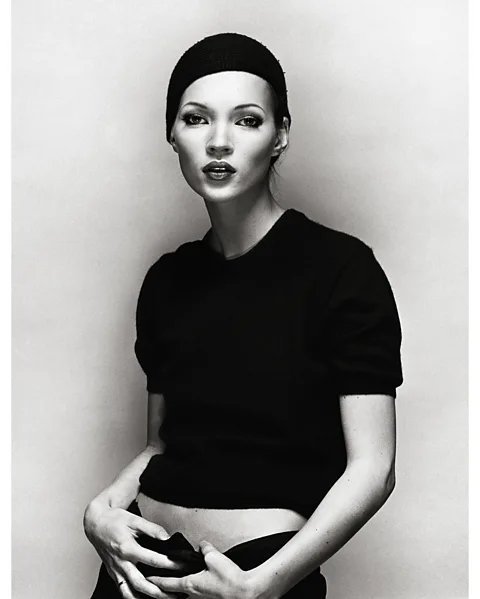

Inez & Vinoodh/ courtesy of the Ravestijn GalleryIt wasn't long before the new aesthetic sparked by the summer of love shoot was influencing the commercial world, most noticeably in advertising campaigns by Calvin Klein with Moss for Obsession, and with Moss and Mark Wahlberg for the brand's underwear. In subsequent issues, The Face continued to reflect the optimistic feeling about the decade ahead – one cover story shot by Day, and titled Young Style Rebels, featured "five faces for the 90s" with Moss, Rosemary Ferguson, Lorraine Pascale and other models who departed from the 80s "glamazon" norm. "After the supermodels, a new generation is coming through with new ideas and attitude" said the introduction.

The next time the Moss-Day pairing caught the public's attention was with a 1993 fashion story for British Vogue, in which a very thin Moss posed in underwear in a downbeat bedroom. They were again defiantly unglitzy images, but this time – perhaps because of the context of the venerable magazine in which they appeared – they provoked outrage. Grunge fashion, waif style and "heroin chic" became phrases used in the British tabloid newspapers.

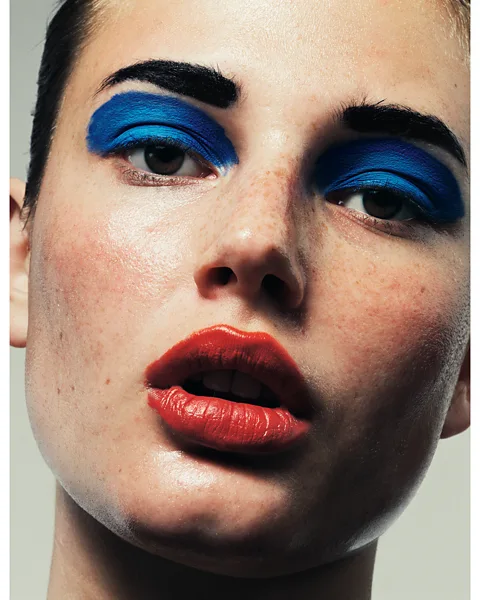

The Face was soon moving on to its next phase of the 90s – a succession of new lads and ladettes, grunge and Britpop bands, and edgy young British artists (known collectively as "the YBAs") all adorned the covers of big-selling issues of the magazine, which from 1993 had a fresh look, courtesy of Swillingham, the new art director. "There was a kind of shift. From reality to anti-reality, technology and retouching, a more kinetic, colourful feel," he says. Swillingham commissioned photographers such as Norbert Schoerner and Elaine Constantine, and the resulting aesthetic was, again, soon adopted by the commercial world, with numerous ads influenced by the colour-drenched, hyperreal style – notably a 1995 ad for Levi's.

Elaine Constantine

Elaine ConstantineNew Labour was on the horizon. The Face was, says McRobbie, central to the "post-industrial creative economy, which was welcomed by Tony Blair and New Labour". In 1997, artists, pop bands – including Oasis – and fashion folk were invited to 10 Downing Street by then British Prime Minister Blair. In the same year, Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit adorned the front cover of prestigious US magazine Vanity Fair with the coverline "London swings again", and the YBAs' Sensation exhibition showed at the Royal Academy. Cool Britannia was born. "Just as the Swinging London of the 1960s was a moment of great creativity and entrepreneurship, so was the 1990s," says McRobbie.

Then and now

Some have argued that the late 80s and early 90s rave movement in Britain was a moment of conscious uprising and egalitarian protest, a uniquely anarchic outpouring with its hedonistic, unruly origins in the country's chaotic and distinctive folk rituals. It is argued that it was a coming together of all genders, races and classes, and a significant movement that resonates now – and has enjoyed a recent revival. For others, it is a collective memory of joy. There's no doubt the movement drew from a broad sweep of society – its adherents gathered from far and wide, from the football terraces, the suburbs, the inner cities, student campuses, the home counties. And certainly, there were protests around the introduction by the government of a bill brought in to end illegal raves.

However, according to McRobbie, rave was not a movement about ideas or politics. "The rave scene and the waif look weren't political. The movement evolved and became about jobs and entrepreneurship, eventually becoming the creative industries in fashion, music and more. The legacy of The Face is that it kickstarted a valuable – to the economy – celebrity culture, big industries and sponsorship deals."

Lee Swillingham echoes this: "Fashion got industrialised in the 2000s, brands got bigger, and were bought out by big groups. High fashion became industrialised, and The Face was part of that change. The magazine started getting more advertising, though we were still outsiders." This phase in pop culture of the late 2000s and 2010s – which was dominated by a grimy, hedonistic look, and the sounds of bands like The Strokes and The Libertines – was later revived and reincarnated in the 2020s as the Indie Sleaze aesthetic.

David Sims

David SimsSadly photographer Corinne Day died from a brain tumour in 2010 – her photographs have been exhibited at the V&A, Tate Modern, Saatchi Gallery and Photographers' Gallery, among others. Many of the other names associated with the fashion and photography of The Face became central to the fashion-celebrity industrial complex – not least, of course, Kate Moss, as iconic as ever. Swillingham went on to work at Vogue with Edward Enninful (who had been at fellow style magazine ID). Photographers including Ellen von Unwerth, Nigel Shafran, Kevin Davies, David Sims, Glen Luchford, Juergen Teller, Inez & Vinoodh, Elaine Constantine and others went on to have profitable careers in the commercial world, "at the centre of the contemporary fashion industry" says Swillingham, who is now consultant art director of Harper’s Bazaar Italia and has his own creative agency, Suburbia. As Bicker – now an international, award-winning creative director – puts it: "Ultimately the only way the industry could take some control over the young disruptors was to embrace its protagonists."

It is perhaps difficult to imagine now in our digital age, but there was a sense of cultural cohesion about this time – and the way it was distilled and chronicled – that we won't see again. As McRobbie puts it: "The Face marks out a pathway to social fragmentation. There was a coherence which was impressive about The Face, and that has been dismantled in the digital age, which is a loss." Swillingham loved the "ephemeral" nature of things then, and remembers his time at The Face as the most exciting job he ever had: "We didn't have time to think about it, we were in it."

The Face Magazine: Culture Shift is at the National Portrait Gallery, London from 20 February to 18 May.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.