'I heard the sirens go and I was all wobbly at the knees': The life-changing day World War Two began

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBritain went to war with Hitler's Germany on 3 September 1939. In History revisits people's recollections of that day and looks at the chilling announcements that transformed public life in an instant.

"We weren't afraid, not us youngsters, because it was a new experience for us. As far as the older people, they were very apprehensive about it."

Looking back at the day when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany, the words of one London shopkeeper summed up the generation gap between those who had lived through what would soon become known as World War One and those not old enough to remember the grim conflict. Only 21 years had passed since the Great War, and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had tried desperately to prevent another catastrophic fight with Germany.

Just a year earlier, Chamberlain claimed "peace for our time" had been secured by the Munich Agreement, when Britain and France had let Adolf Hitler get away with stealing the Sudetenland from neighbouring Czechoslovakia, as long as he didn't try to claim any more land. In March 1939, Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia, breaking the terms of the treaty. Then on Friday 1 September 1939, he launched a ferocious attack on Poland, Nazi Germany's weaker neighbour. Hitler had calculated that Poland's allies Britain and France would not react to this latest provocation.

But Chamberlain's policy of appeasing Hitler's aggression could not stand any longer. Britain issued an ultimatum on Saturday that if Hitler failed to withdraw his forces, there would be war. This final warning expired at 11:00 on Sunday morning.

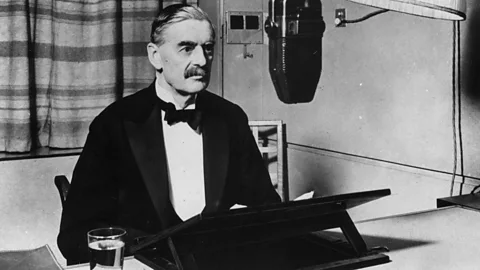

Fifteen minutes later, Chamberlain was sat down in front of a BBC microphone in the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street, his official residence. BBC newsreader Alvar Lidell was there with him. Looking back 30 years later, he described the scene: "Chamberlain was sitting alone and his demeanour was that of a worn-out, broken man. The red light came on steady. I leaned over his shoulder, put him on the air and then sat down behind him and was alone in the room with him throughout this momentous speech."

In his broadcast, Chamberlain said: "You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win peace has failed." He said Hitler's invasion of Poland "shows convincingly that there is no chance of expecting that this man will ever give up his practice of using force to gain his will - he can only be stopped by force". He added: "It is evil things that we shall be fighting against - brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution - and against them I am certain that right will prevail."

Chamberlain urged people to pay close attention to the announcements that would follow his broadcast, adding: "The government have made plans under which it will be possible to carry on the work of the nation in the days of stress and strain that may be ahead."

As people tried to digest this news, the following announcements would transform everyday life to an extent not seen again until the first Covid-19 lockdown in March 2020. All entertainment venues such as cinemas and theatres would be closed immediately until further notice, and large public gatherings such as sports events were also banned. "They are being closed because if they were hit by a bomb, large numbers would be killed or injured," the government said in a statement read by Lidell.

Britain was braced for an all-out attack from the air within minutes of war being declared. People were told: "In the event of threatened air raids, warnings will be given in urban areas by means of sirens or hooters which will be sounded in some places by short intermittent blasts, and in other places by a warbling note changing every few seconds. The warning may also be given by short blasts on police whistles."

It was a lot of information to commit to memory and recall amid the panic of an actual attack. "If poison gas has been used, you will be warned by means of hand rattles. If you hear hand rattles, do not leave your shelter until the poison gas has been cleared away. Hand bells will be used to tell you when there is no longer any danger from poison gas." Rattles mean danger, bells mean safety? Got it.

The announcement carried unspoken implications about the need to make it easier for the authorities to identify the dead. "Carry your gas mask with you always. Make sure that you and every member of your household, especially children able to run about, have on them their names and address clearly written. Do this either on an envelope or something like a luggage label, not on an odd piece of paper which might get lost. Sew the label onto your children's clothes where they cannot pull it off."

While many dreaded the news of war, preparations had been under way for a while amid Hitler's continued aggression. Thousands of children were evacuated from towns and cities in the days before. Even a year earlier, the BBC had announced government plans for precautionary defence measures. As well as mobilisation of volunteer Territorial Army anti-aircraft and coastal defence units, leaflets were circulated on what to do during an air raid, trenches were dug in parks and gas masks were distributed. The government later had to urge curious and impatient people not to test their masks with gas ovens or car exhaust pipes. In April 1939, conscription of civilians was introduced. By the time war arrived, more than 1.5 million sturdy metal air-raid shelters had been provided for people to dig into their gardens.

A 'world-shattering pronouncement'

Within minutes of Chamberlain's declaration of war, air-raid sirens went off across London. In 1969, 30 years later to the day, the BBC pulled together people's memories of that moment in a programme titled Where Were You on the Day War Broke Out? One woman said: "I heard the sirens go and I was all wobbly at the knees." Another remembered seeing dock workers running for their lives. Some were surprised by their own reaction to the announcement, like one woman who said: "It was the most wonderful thing to imagine to find that far from feeling sick with terror, I felt so exhilarated, so excited, so pleased with myself."

One man caught outside when the sirens sounded asked someone if he could take cover in their garden air-raid shelter, only to be told there was no room. He said the householder told him: "I was the only one down this turning that decided to have a shelter. As soon as the siren went, all my neighbours climbed over the back fences and went into my shelter. Look at them… like a lot of bloody rabbits." Another man admitted he was playing tennis when the sirens went, "and we belted home as quick as we could".

IN HISTORY

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Newsreader Lidell recalled feeling surprised that even though war was expected, not everyone was gathered around the wireless. He said: "One saw people strolling about in the sunshine - it was a lovely morning - completely oblivious of what was going on in the Cabinet Room, this world-shattering pronouncement which was being made. One couldn't really grasp the reality. In the same way as when someone close to you has died, you don't really grasp it immediately. And almost precisely as those thoughts went through my mind, the air raid sirens sounded." Fortunately this time, it was a false alarm. London would not be so lucky in the years to come.

France declared war on Germany five hours after Britain. US President Franklin D Roosevelt was keen to maintain American neutrality, wary of entering what was seen as a European conflict. In one of his famous broadcast fireside chats that evening, he said: "This nation will remain a neutral nation. But I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well."

At 18:00, King George VI broadcast from Buckingham Palace to his subjects in Britain and the Commonwealth. Urging people to "stand calm, firm and united in this time of trial," he said: "The task will be hard, there may be dark days ahead and war can no longer be confined to the battlefield, but… with God's help, we shall prevail." The story of his own personal difficulties leading up to him making this radio broadcast was depicted in the 2010 film, The King's Speech.

In Berlin, one woman had to wait until the evening to listen to the news from England because "it was pain of death if you listened to foreign radio". Christabel Bielenberg, an English woman married to a German, said it had been "a perfectly glorious early autumn day" but the atmosphere was subdued. She said: "There was no enthusiasm in Berlin whatsoever for the war."

Despite the newspaper headlines warning of imminent war, she said: "I honestly didn't believe it, because we got so used to believing nothing in those days. I didn't believe it when I heard that this was going on."

"In the evening, we turned on the Nine O'Clock News, and a very great friend of my husband's was staying with us at the time, Adam von Trott, who was later hanged by Hitler. And I remember the three of us turning on the radio and I think it was the quietness of the way he announced that Germany and England were at war that made me realise it was true."

After the terror of air-raid sirens sounding in London, what followed in Britain over the next six months was a period sometimes referred to as the Phoney War, a time of high tension but no falling bombs. By late spring of 1940, only a few people were still carrying their gas masks and unused air-raid shelters were filling up with water. It wasn't until 7 September 1940 that the skies first darkened over southern England, and German bombers began its almost continuous aerial bombardment. More than 40,000 civilians would be killed by German bombs during the eight terrifying months of the Blitz.

Chamberlain resigned as prime minister in May 1940. He died of cancer that November. Three days after his death, his successor Winston Churchill paid tribute to him in the House of Commons.

"Whatever else history may or may not say about these terrible, tremendous years, we can be sure that Neville Chamberlain acted with perfect sincerity according to his lights and strove to the utmost of his capacity and authority, which were powerful, to save the world from the awful, devastating struggle in which we are now engaged. This alone will stand him in good stead as far as what is called the verdict of history is concerned."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.