Seven of the Paris Olympics' most striking images – as classical artworks

AP

APAs the 2024 Paris Olympics draws to a close, the BBC rounds up some of the most stunning photos captured from the Games – and reveals their similarities to historic works of art.

The ancient Olympic Games were already a quarter of a millennium old when, in 530 BC, an anonymous Greek artist, known today as the "The Running Man Painter", adorned the body of a clay jug with a playful portrait of a muscular marathonist in full sprint.

Suspended in mid-stride on the vessel's cylindrical surface, the figure's unforgettable flex of form and fleet-footed physique remind us that, since antiquity, athletic expressiveness and artistic expression have striven to keep pace with each other. The line between art and sport is a blurry one.

To this day, the striking photos of exceptional Olympic moments that go viral resonate so powerfully in part because they recall and reinforce iconic images from the history of visual culture that have helped shape our consciousness. We've seen these figures before – only now, they're real. What follows is a curated round-up of some of the most memorable photos captured during the 2024 Paris Olympics, side-by-side with the paintings, drawings and sculptures whose contours they echo.

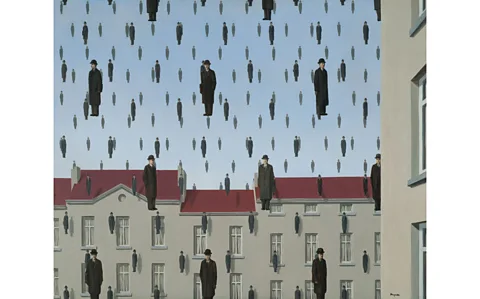

Divers/Magritte's Golconda

Reuters

Reuters The Menil Collection/ C Herscovici/ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

The Menil Collection/ C Herscovici/ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024The choreographed cascade of parallel plunging bodies in a photograph of Great Britain's Anthony Harding and Jack Laugher, competing on 2 August in the men's synchronised 3m springboard diving final, boldly blurred the divers' falling flesh into a static rush of blue mist. The surreal sense of anthropomorphised rain calls to mind Belgian Surrealist René Magritte's frozen shower of bowler-hatted men in his painting Golconda, which also seems to defy the gravity of logic and the logic of gravity.

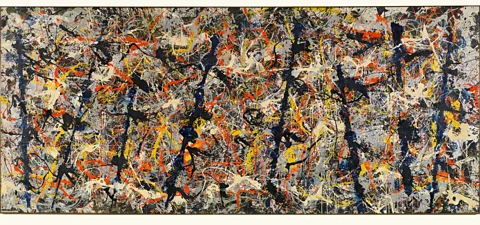

Swimmers/Pollack's Blue Poles

AP

AP National Gallery of Australia © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS and DACS

National Gallery of Australia © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS and DACSAn aerial photo of the colourful chaos of froth and flailing limbs created when athletes competed in the swimming leg of the women's individual triathlon on 31 July seemed a celebration of disorder. One must scrutinise the turbulent tapestry of water and tattoos in order to discern the fragmentary shape of an arm here or a leg there, as the furious scramble of muscle threatens to capsize our senses. The choppy surface calls to mind the mesmerising mêlée of flung and dribbled pigment in US artist Jackson Pollock's painting Blue Poles – a canvas that conceals, under its intense tangle of splashes, shards of broken glass and the bloody footprints of the artist, who is said to have walked across the work while it was still wet.

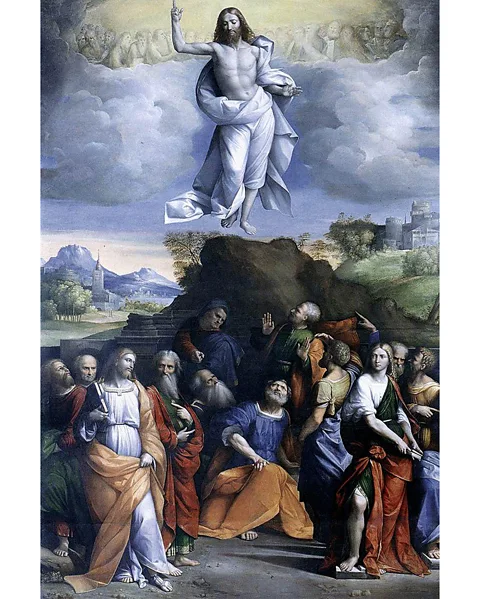

Gabriel Medina/Garofalo's Ascension of Christ

Getty Images

Getty Images Alamy

AlamyThe ultra-viral photo of Brazil's Gabriel Medina floating heavenward after tackling a huge wave off the French Polynesian Island of Tahiti in round three of the men's surfing heats on 29 July, recalled countless religious representations of mystical ascension. What seemed to seal the surprising synchronicity of secular pose with spiritual ascent was Medina's raised right arm and the thrust of his index finger, pointing precisely to where his body and soul appeared to be heading.

Triathlon/Raffaello's Spozalizio

Reuters

Reuters Pinacoteca Brera

Pinacoteca BreraA message posted to X (formerly Twitter) on 31 July by a like-minded user of the social media platform intrigued the internet, attracting more that 5 million views. Beneath a TV screenshot, @EmmaTurnerBA confessed that she was "obsessed with the finish line in the men's triathlon, it's like a renaissance piece". Precisely which canvas these various vignettes of kneeling, collapsing, embracing and loitering brought to mind wasn't clear. A Veronese, perhaps? A Botticelli? Or perhaps it isn't the huddles of mind and muscle that rhymes with any particular painting, but the fabulous framing of the momentous scene – how it draws our eye, Raphael-style, to the grandeur of a glistening palace in the distance.

Boxers/Mahonri Young's sculpture

Getty Images

Getty Images Smithsonian American Museum Modern Art

Smithsonian American Museum Modern ArtIt is the unsettling length of the accelerating arm, flying in from the right, and punctuated by a blood-red disembodied glove that is so, well, striking. The photo, which captures the disconnection between the eyes of Spain's Enmanuel Reyes, who sees the punch by Belgium's Victor Schelstraete coming, and his body's inability to stop the brutal blow, is jaw-dropping. Nearly a century ago, the US sculptor Mahonri Young found himself hooked on a trip to Paris in 1926 by comparable hooks, which he translated into celebrated bronze sculptures of prizefighters. His unflinching statue Right to the Jaw is right to the point.

Anthony Jeanjean/Man falling from the Sky

Alamy

Alamy The National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of ArtThe tapering peak of the obelisk that rises behind French cyclist Anthony Jeanjean, captured in midair as he competes in the BMX Freestyle events on 31 July, may be pointing upwards but we all know which way gravity will ultimately drag him. However perilous, Jeanjean's weightlessness is exhilarating. The thrilling photo calls to mind the endlessly unended plummet of a figure in a 17th-Century work on paper by an unknown Flemish artist, entitled Man Falling from the Sky. How exactly the imperilled figure wheeled his way to his elevated perch isn't immediately apparent. Like Jeanjean, like us, all he can do is keep on pedalling.

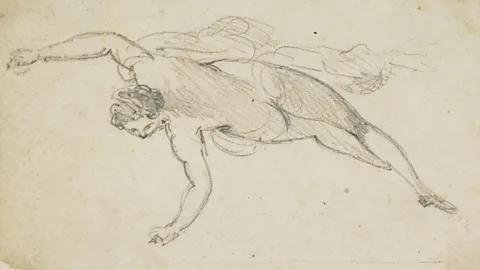

Simone Biles/Edmund Thomas Parris's Flying Figure

AP

AP National Galleries Scotland

National Galleries ScotlandThe split-second snap of US gymnast Simone Biles – bolting horizontally through the air as she performs on the floor during the women's artistic team finals on 30 July – seems like a still from a superhero film. This is goddess-grade grace, and one could easily summon the floating elegance of any number of Classical representations of winged figures, from Isis to Artemis, Aphrodite to Nike, to soar alongside Biles. Or perhaps the fleeting flight of an anonymous female flyer, magicked into eternal levitation from a few fragile lines of pencil by the 19th-Century London artist Edmund Thomas Parris, does the trick best – its exquisite simplicity belying its brilliance.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

Want to read more about the Olympics? Sign up for Medal Moments, your free global guide to Paris 2024, delivered daily to your inbox throughout the Games.