How Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury group unbuttoned Britain

Alamy

AlamyCounting Virginia Woolf among their number, the Bloomsbury group were radical creative figures in the early 20th Century. A new exhibition explores how that extended to their wardrobes too, writes Holly Williams.

"Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world's view of us." So wrote Virginia Woolf in her 1928 novel Orlando, about a young nobleman who lives for several centuries, changing sex along the way.

Woolf often uses Orlando's changes in clothing to say something about the changing times and gender expectations they live under. A young male Orlando may romp through the countryside or ice skate along the Thames, but the female Orlando in the 18th and 19th Centuries is as hampered by crinolines as she is by the way society suddenly sees her as delicate and enfeebled. Eventually, she embraces androgyny, and starts wearing breeches – just as Woolf's lover, and inspiration for Orlando, Vita Sackville-West was wont to do.

Weiner Staatsoper / Michael Poehn

Weiner Staatsoper / Michael PoehnBut Woolf's handily quotable maxim that clothes "change our view of the world and the world's view of us" could have been taken from a new book and exhibition about the Bloomsbury Group – the radical circle of artists, writers, and thinkers that Woolf was a part of. Fashion journalist Charlie Porter's book, Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion, has been published to coincide with the show he's curated at Charleston in Lewes, a new exhibition space in Sussex near the famous farmhouse where several of the Bloomsbury Group lived.

"Virginia Woolf recognised that to understand humans you have to understand clothes," he says when we meet at the gallery. "Clothes aren't just a decorative punctuation point."

The Bloomsbury Group were radical in many ways: in their work, they exhibited a restless questing for new forms, on the page or the canvas. In their philosophy, they were pioneers across fields as various as feminism, pacifism, art theory and economics. And in their personal lives, they were famously fluid too – many were queer, and their romantic and sexual relationships were often non-monogamous and mutually entangled.

'Bring no clothes'

But they were also, Porter argues, radical when it came to what they wore, and what their clothing meant. His title, Bring No Clothes, turns offhand comments made by Woolf into a pithy manifesto: it's a phrase she often wrote to visitors, a promise of unconventionality. Porter quotes a letter Woolf sent to TS Eliot in 1920, ahead of his visit to her Sussex cottage: "We are hoping to see you on Saturday… Please bring no clothes: we live in a state of the greatest simplicity." This instruction ensured guests knew that they wouldn't have to conform to the upper-class expectation of dressing for dinner – that they were rejecting hierarchies shored up by the very concept of appropriate attire.

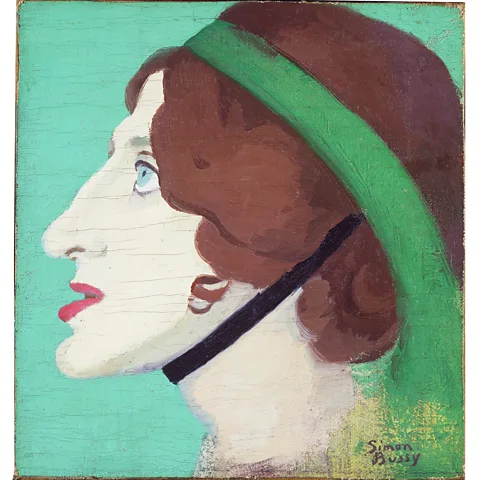

Tate/ Estate of Simon Bussy

Tate/ Estate of Simon BussyOf course, the Bloomsbury Group weren't romping about with no clothes on at all (with the exception of the painter Duncan Grant, who seems to have loved stripping off). But our popular conception of what they were wearing has become perhaps over-simplified in recent decades.

The idea of the "Bloomsbury look" as an identifiable style is well-cemented. It feels like every few years, a fashion designer references them on the catwalk, and magazines follow with shoots of how to "get the look". Porter summarises the "Bloomsbury look" thusly: "It's a loose longline floaty patterned dress, or a cardigan over a blouse that's buttoned up – in can be really librarian, in this demeaning view of librarians!"

And this was something Porter was interested in interrogating – for it does something of a disservice to this colourful lot. For starters, even deciding who is in or out of "the Bloomsbury Group" is tricky. With upwards of 20 potential Bloomsbury-ites, spanning multiple decades and even generations, it's hardly surprising that many of them dressed very differently to one another.

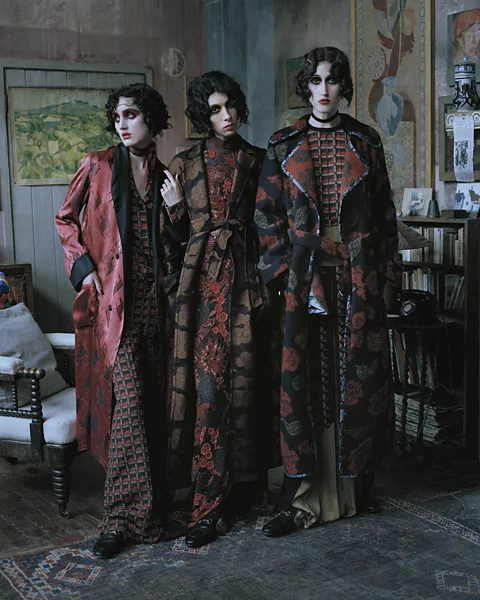

Brett Lloyd

Brett Lloyd"The idea of the 'Bloomsbury look' is a pretty floral dress, but it should actually also be the tailored suit," points out Porter. He explores how if you look at, say, the novelist EM Forster or the economist Maynard Keynes, you'd hardly cry looseness and freedom – they're usually seen in a classic suit, the uniform of patriarchal, imperial, entitled, buttoned-up British power. They are also using the suit to hide their true identity as men who love men; a way to pass in an era when homosexuality was illegal. This does not look like throwing off the shackles, as other members of the group more openly did.

And there are some more obvious Bloomsbury sartorial rebels: figures like Woolf and her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, and her lover Grant, who rejected restrictive clothing in favour of dishevelment, comfort and flow. Women like Dora Carrington, the painter, or Sackville-West, who consciously embraced androgyny. Or Lady Ottoline Morrell, who forged her own unabashed and inimitable style, wearing elaborate dresses that were considered deeply unfashionable.

Yet we still have a tendency to get things about them wrong. It is true, for instance, that Woolf and Bell did float around in waistless, longline, drapey garms. But the entrenched idea that these were always in muted tones – mauves and sage, brown and dulled blues (think of the murky colour palette in The Hours, or the similarly restrained BBC drama Life in Squares) seems to be, at least in part, due to assumptions derived from the fact that they were always photographed in black and white.

Reports from the time suggest many of the set were actually big into bold colour – exactly as you'd expect, if you looked at Bell and Grant's paintings or at Charleston, where they painted every available surface in mustard, tangerine, chartreuse and turquoise, as well as softer pastels.

It was something that really struck Porter in his research. "The number of times people talked about the jarring colours they wore… these vile clashes," he recalls. He quotes Bell writing to Grant in 1915, asking for her yellow waistcoat – and one can only imagine what she was planning on pairing it with. "I am going to make myself a new dress," she continued, adding, "you won't like the dress I'm afraid, as it will be mostly purple… Also I'm going to make myself a bright green blouse or coat". As Porter points out, these are "bold colour fields, just like her abstracts".

A rejection of old mores

Bloomsbury was self-consciously revolutionary in various artistic ways – as early as 1908, Woolf was insisting that she wanted to do nothing less than "re-form the novel" – and so it is tempting to assume that they were all planning out this fashion revolution, determining to "make it new" (as fellow modernist Ezra Pound famously said).

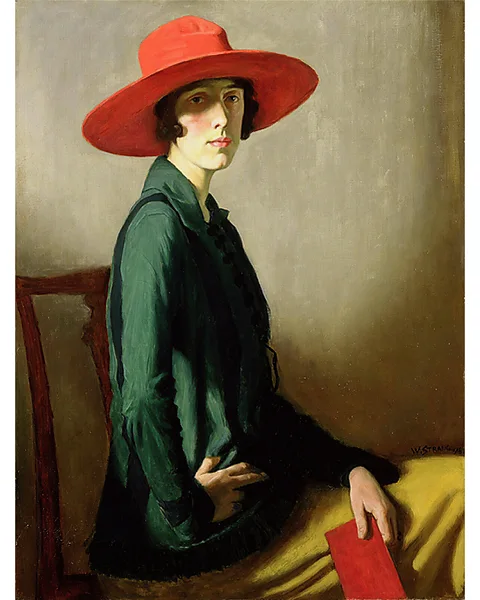

Alamy

AlamyYet for Porter, the key to understanding the Bloomsbury look is not to see it as a bold new style, but as a bold rejection of an oppressive old one. "The radicalism is in the refusal," he says – the Bloomsbury look is as much about saying no to what came before as about finding a new way to be.

"The way we see fashion is in terms of next season, next season, and the way we historicise it is often as this series of forward movements. But I actually think refusal is as powerful a force – it's rejection and it's breaking, and that then allows for change," says Porter. "Rather than 'hey I really feel like wearing a long-sleeve floaty dress', it's that that's what available at the time, that they can exist in society wearing without being damned, while still rejecting restrictive clothing."

So, what were the Bloomsberries rejecting, and reacting against? The term "restrictive clothing" isn't an exaggeration. Woolf and Bell grew up in an era, and in a class, where they still had to dress for dinner, and were expected to spend their evenings at society parties that they loathed. Dressing correctly was paramount, and for young women this involved wearing stays – boned corsets – underneath full length, often lavish dresses. Woolf hated the restrictions of stays – she wrote to her first love, Violet Dickinson, "I tried to saw mine through this morning, but couldn't. What iron boned conventionality we live in…"

Woolf was sexually abused as a child by her own half-brother, a trauma that seemed to result in extremely complicated feelings towards her body, her appearance, and her sexuality; she wrote about experiencing "looking-glass shame" when catching her own reflection. In 1939 she wrote "everything to do with dress … still frightens me".

Being paraded around society in shoulder-revealing evening gowns and pearls decided on by that self-same half-brother sounds like it was a kind of torture for her. It is one of the reasons why Porter finds the fetishising of "the Bloomsbury look" uneasy: for Woolf it may have been more about escaping trauma, comfortably covering up the body, than about crafting some fashionable design.

It was in 1904 when Woolf and Bell escaped into their own London home – 46 Gordon Square – and decided to do things differently. "Everything was going to be new," wrote Woolf in 1920, looking back at this time. "Everything was going to be different. Everything was on trial." This meant upending conventions about how to socialise, including what to wear.

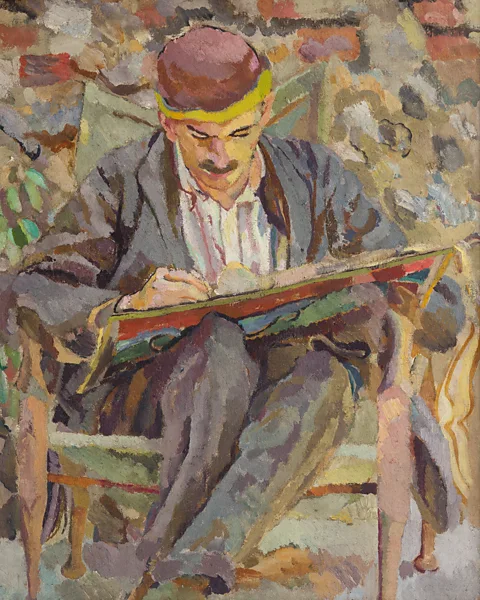

Estate of Duncan Grant

Estate of Duncan GrantTheir brother Thoby began bringing over friends from Cambridge, and the Bloomsbury group formed during Thursday evening get-togethers. These were deliberately informal: "It was late at night; the room was full of smoke; buns, coffee and whisky were strewn about; we were not wearing white satin or seed pearls; we were not dressed at all," wrote Woolf.

And these intelligent, highly-educated young men seemed more interested in a large mind than a tiny waist. Woolf wrote of how they "criticised our arguments as severely as their own… They never seemed to notice how we were dressed or if we were nice looking or not". It was a relief, and a thrill – at last the sisters could breathe freely, think freely, and be listened to, rather than looked at.

"This refusal of what they'd been forced to wear in their upbringing was as important as everything going on around them, in the ideas they were sharing, the conversations they were having," says Porter.

But increasingly, there came a practical element to their dress choices – something seen most clearly via Bell and Grant. Moving to Charleston farmhouse in 1916, the rumpled informality of their clothing – often hand-made garments, kept together with safety pins; usually covered in paint or dirt, almost always capacious, revealing even – speaks to both life in the countryside and to their lives as painters. So while there was an intellectual philosophy behind throwing off the shackles of Victorian decorum, there was also just the practical imperative to be able to move freely through the world, to create art unencumbered by tight sleeves or pinched waists.

Tim Walker

Tim WalkerIt wasn't just the Bloomsbury group who were embracing new shapes, of course. The 20th Century saw a general turn away from restrictive, rigidly codified clothing – and Porter isn't arguing that Bloomsbury were the architects of this shift. But they do form a useful historical snapshot: a much-documented group of friends figuring out how to live, love and dress differently.

"I am by no means saying that they changed fashion, in themselves, but I don't know of another collective that we can study in this way. Through their example we can shine a light on what was happening among other young people at that time. And I do think they are a very remarkable example of queer humans finding each other," he says.

"In many cases they could only go so far – but it was extraordinary what they attempted to do, with their desire for change."

Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion by Charlie Porter is published by Particular Books; Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion is at Charleston in Lewes, UK, until 7 January 2024

'What Time is Love?' by Holly Williams is published by Orion

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.