Why adults should read children's books

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe best children's fiction "helps us refind things we may not even know we have lost", writes the author Katherine Rundell, with many books proving subversive, emboldening – and awe-inspiring.

I've been writing children's fiction for more than 10 years now, and still I would hesitate to define it. But I do know, with more certainty than I usually feel about anything, what it is not: it's not exclusively for children. When I write, I write for two people: myself, age 12, and myself, now, and the book must satisfy two distinct but connected appetites. My 12-year-old self wanted autonomy, peril, justice, food, and above all a kind of density of atmosphere into which I could step and be engulfed. My adult self wants all those things, and also: acknowledgements of fear, love, failure; of the rat that lives within the human heart. So what I try for when I write – failing often, but trying – is to put down in as few words as I can the things that I most urgently and desperately want children to know and adults to remember. Those who write for children are trying to arm them for the life ahead with everything we can find that is true. And perhaps, also, secretly, to arm adults against those necessary compromises and necessary heartbreaks that life involves: to remind them that there are and always will be great, sustaining truths to which we can return.

More like this:

- The 100 greatest children's books of all time

- Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children's book

There is, though, a sense among most adults that we should only read in one direction, because to do otherwise would be to regress or retreat: to de-mature. You pass Spot the Dog, battle past that two-headed monster Peter and Jane; through Narnia, on to The Catcher in the Rye or Patrick Ness, and from there to adult fiction, where you remain, triumphant, never glancing back, because to glance back would be to lose ground.

But the human heart is not a linear train ride. That isn't how people actually read; at least, it's not how I've ever read. I learned to read fairly late, with much strain and agonising until, at last and quite suddenly, the hieroglyphs took shape and meaning: and then I read with the same omnivorous un-scrupulosity I showed at mealtimes. I read Matilda alongside Jane Austen, Narnia and Agatha Christie; I took Diana Wynne Jones's Howl's Moving Castle with me to university, clutched tight to my chest like a life raft. I still read Paddington when I need to believe, as Michael Bond does, that the world's miracles are more powerful than its chaos. For reading not to become something that we do for anxious self-optimisation – for it not to be akin to buying high-spec trainers and a gym membership each January – all texts must be open, to all people.

The difficulties with the rule of readerly progression are many: one is that, if one follows the same pattern into adulthood, turning always to books of obvious increasing complexity, you're left ultimately with nothing but Finnegans Wake and the complete works of the French deconstructionist theorist Jacques Derrida to cheer your deathbed.

The other difficulty with the rule is that it supposes that children's fiction can safely be discarded. I would say we do so at our peril, for we discard in adulthood a casket of wonders which, read with an adult eye, have a different kind of alchemy in them.

WH Auden wrote "There are good books which are only for adults, because their comprehension presupposes adult experiences, but there are no good books which are only for children."

I am absolutely not suggesting adults read only, or even primarily, children's fiction. Just that there are times in life when it might be the only thing that will do.

What is it like to read as a child? Is there something in it – the headlong, hungry, immersive quality of it – that we can get back to? When I was young I read with a rage to understand. Adult memories of how we once read are often de-spiked by nostalgia, but my need for books as a child was sharp and urgent and furious if thwarted. My family was large, and reading offered privacy from the raucous, mildly unhinged panopticon that is living with three siblings: I could be sitting alongside them in the car, but, in fact, it was the only time when nobody in the world knew where I was. Crawling through dark tunnels in the company of hobbits, standing in front of oncoming trains waving a red flag torn from a petticoat: to read alone is to step into an infinite space where none can follow.

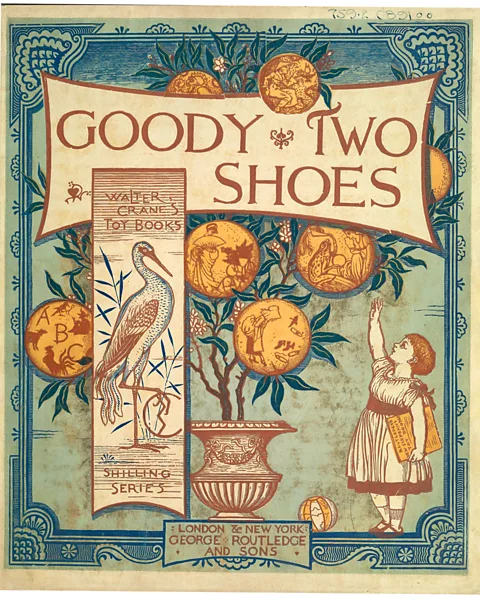

How children's fiction came to be

The first children's books in English were instruction manuals for good behaviour. My favourite, and the sternest in tone, is The Babees' Book, which dates in manuscript from around 1475: "O Babees young," writes the author, "My Book only is made for your learning." The text is a monumental list of instructions in verse form: "Youre nose, your teethe, your naylles, from pykynge/Kepe at your mete, for so techis the wyse."

Alamy

AlamyIn 1715, Isaac Watts published his fantastically uncheerful Divine and Moral Songs for Children. I find this book fascinating because its author's preface shows that by the 18th Century, the idea that it was intellectually degrading to write for children was strong: Watts writes, "I well know that some of my particular friends imagine my time is employed in too mean a service while I write for babes... But I content myself with this thought, that nothing is too mean for a servant of Christ to engage in, if he can thereby most effectually promote the kingdom of his blessed Master." The book itself fits into the category, popular at the time, of "upliftingly lugubrious"; it is largely made up of briskly invigorating rhymes about the inevitability of death:

Then I'll not be proud of my youth or my beauty,

Since both of them wither and fade;

But gain a good name by well doing my duty:

This will scent like a rose when I'm dead.

In 1744 came what's often called the first work of published children's literature, John Newbery's A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, Intended for the Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly. With Two Letters from Jack the Giant Killer; as also a Ball and Pincushion; The Use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good Boy, and.

Newbery's text is actually wittier than it sounds, shot through with a vein of irony, but its ancestry was clear: it came from a history of pedagogical texts and situated itself among them. Newbery's text set a pattern: children's books would be instructive first and entertaining second.

Subversive tales

Alongside the morally uplifting accounts of Sunday schools and rigorously unpicked noses, though, there was another kind of story evolving, of a more unruly and subversive kind: the fairy tale.

Fairy tales were never just for children. They are determinedly, pugnaciously, for everyone – old and young, men and women, of every nation. Esteemed fairy tale expert Marina Warner argues that fairy tales are the closest thing we have to a cultural Esperanto: whether German, Persian, American, we tell the same fairy tales, because the stories have migrated across borders as freely as birds.

All fairy tales, by and large, have the same core ingredients: there will be the archetypal characters – stepmothers, powerful kings, talking animals. There will be injustice or conflict, often gory and extravagant, told in a matter-of-fact tone that does nothing to shield children or adults from its blunt bloodiness. But there will also usually be something – a fairy godmother, a spell, a magic tree – which brings the miracle of hope into the story. "Fairy tales," Warner writes, "evoke every kind of violence, injustice and mischance, but in order to declare it need not continue." Fairy tales conjure fear in order to tell us that we need not be so afraid. Angela Carter saw the godmother as shorthand for what she calls "heroic optimism". Hope, in fairy tales, is sharper than teeth.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat spirit of heroic optimism – optimism blood-covered and gasping, but still optimism – is the life principle writ large. It speaks to us all: because fairy tales were always designed to be a way of talking to everyone at once. They provide us with a model for how certain kinds of stories – by dealing in archetypes and bassnote human desires, and in metaphors with bite – can yoke together people of every age and background, luring us all, witch-like, into the same imaginative space.

Fairy tales, myths, legends: these are the foundations of so much, and as adults we need to keep reading them and writing them, repossessing them as they possess us.

It was in the middle of the 19th Century, as paper became more affordable and childhood literacy rates soared, that children's fiction began to take the actual desires of children into account. The subversive hunger of fairy tales, unleashed into the newly booming printing press, made its way into children's novels. Stories designed for children were unhitched from the schoolroom and the pulpit, and the First Golden Age of children's books was born. Lewis Carroll, Rudyard Kipling, JM Barrie and E Nesbit killed the parents, or abandoned them, or left them when they fell or flew to Wonderland or Neverland, and in so doing they released the child from the imperatives of the adult world. It must have felt like dynamite. Orphaned and unsupervised children roamed through Storyland, wreaking the chaos necessary for an adventure to take place. Larger and wilder experiences were on offer: stories which pushed back at the edges of what was possible.

It was here that the idea that children were sweet or gentle or necessarily more simple or likeable than other kinds of humans was jettisoned, along with the idea that all logic must be adult logic. As a child, I had no illusions that children were sweet: children, I knew from my own furious heart, were frequently nasty, brutish and short. In casting aside that idea, children's books began to play by their own rules and, in so doing, became works of art distinct in themselves, in their own tradition, not watered-down versions of some other, adult thing.

And that tradition has held. You could draw a family tree from Peter Pan, who first appeared in 1902 ("and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless"); to Mary Poppins in 1934, with her stern and impenetrable enchantments ("Mary Poppins never explains anything"); to the anarchic and surreal logic of Where the Wild Things Are (1963) and The Tiger Who Came to Tea (1968), who "drank all the water in the tap". (And on to Roald Dahl and Frank Cottrell-Boyce and Lissa Evans and to someone whose name we do not yet know, writing somewhere a story that will shake us in our collective shoes.)

The family tree keeps growing. Children's fiction today is still shot through with exactly the same old furious thirst for justice that characterises fairy tales: the wicked stepmother is beheaded by a trunk, Mrs Coulter in Philip Pullman's The Amber Spyglass (2000) falls eternally through a hole in the tissue of the Universe. And, too, knitted closely into the need for justice, there is a related stance, the happier cousin of protective retribution: that of wonder. In a world which prizes a pose of exhausted knowingness, children's fiction allows itself the unsophisticated stance of awe. Eva Ibbotson escaped Vienna in 1934, after her mother's writing was banned by Hitler; her work is full of an unabashed astonishment at the sheer fact of existence. Journey to the River Sea (2001) has a kind of wonder that other kinds of fiction might be too self-conscious to allow themselves. So it's to children's fiction that you turn if you want to feel awe and hunger and longing for justice: to make the old warhorse heart stamp again in its stall.

Children's books are specifically written to be read by a section of society without political or economic power. People who have no money, no vote, no control over capital or labour or the institutions of state; who navigate the world in their knowledge of their vulnerability. And, by the same measure, by people who are not yet preoccupied by the obligations of labour, not yet skilled in forcing their own prejudices on to other people and chewing at their own hearts. And because at so many times in life, despite what we tell ourselves, adults are powerless too, we as adults must hasten to children's books to be reminded of what we have left to us, whenever we need to start out all over again.

Children's fiction does something else too: it offers to help us refind things we may not even know we have lost. Adult life is full of forgetting; I have forgotten most of the people I have ever met; I've forgotten most of the books I've read, even the ones that changed me forever; I've forgotten most of my epiphanies. And I've forgotten, at various times in my life, how to read: how to lay aside scepticism and fashion and trust myself to a book. At the risk of sounding like a mad optimist: children's fiction can reteach you how to read with an open heart.

When you read children's books, you are given the space to read again as a child: to find your way back, back to the time when new discoveries came daily and when the world was colossal, before your imagination was trimmed and neatened, as if it were an optional extra.

But imagination is not and never has been optional: it is at the heart of everything, the thing that allows us to experience the world from the perspectives of others: the condition precedent of love itself. It was Edmund Burke who first used the term moral imagination in 1790: the ability of ethical perception to step beyond the limits of the fleeting events of each moment and beyond the limits of private experience. For that we need books that are specifically written to feed the imagination, which give the heart and mind a galvanic kick: children's books. Children's books can teach us not just what we have forgotten, but what we have forgotten we have forgotten.

One last thing: I vastly prefer adulthood to childhood – I love voting, and drinking, and working. But there are times in adult life – at least, in mine – when the world has seemed blank and flat and without truth. John Donne wrote about something like it: "The general balm th'hydroptic earth hath drunk,/Whither, as to the bed's feet, life is shrunk,/Dead and interred."

It's in those moments that children's books, for me, do that which nothing else can. Children's books today do still have the ghost of their educative beginnings, but what they are trying to teach us has changed. Children's novels, to me, spoke, and still speak, of hope. They say: look, this is what bravery looks like. This is what generosity looks like. They tell me, through the medium of wizards and lions and talking spiders, that this world we live in is a world of people who tell jokes and work and endure.

Children's books say: the world is huge. They say: hope counts for something. They say: bravery will matter, wit will matter, empathy will matter, love will matter. These things may or may not be true. I do not know. I hope they are. I think it is urgently necessary to hear them and to speak them.

This is an extract taken from Why You Should Read Children's Books, Even Though You are so Old and Wise by Katherine Rundell.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.