The Cloud: The dystopian book that changed Germany

Ravensburger

RavensburgerFor many Germans, The Cloud remains the ultimate "catastrophe book". But did it empower generations of children or leave them traumatised for life, asks Sophie Hardach.

It was an ordinary day in 1986, in what was then West Germany, and I was playing in the garden with one of my brothers. We didn't mind the light rain. I probably wouldn't even remember that afternoon, if it hadn't been for the news that broke the next day: "Apparently, there has been a serious nuclear accident in the Soviet Union," a worried-looking presenter announced on the evening news.

Slowly, more details trickled out. The accident had happened two days before, at the Chernobyl nuclear power station. Clouds had carried radioactive rain over to Germany, and children were told not to play outside. For us, and many of our friends, the warning came too late: we'd already been in that rain, just like the rain-splashed lettuce and mushrooms we were now told not to eat. Diggers arrived to remove the damp, contaminated sand from playgrounds. In our local grocery shop, people walked along the shelves with printed lists in their hands, showing the radioactivity levels of different foods, to check which ones were safe to eat. Many of us could barely grasp the concept of radioactivity. A childhood friend of mine recalls asking her dad some days after the disaster: "Papa, is there still this TV-activity?"

More like this:

Around that time, a then relatively little-known German writer and teacher called Gudrun Pausewang was watching the unfolding events with horror. Her son was away on a hiking trip, and when he called her, she yelled down the phone: "Don't sit down on the grass! It's contaminated!" Pausewang had recently published a children's book about nuclear war, and considered atomic energy an existential threat. Now her fear of a disaster had come true, and she could see the impact even in her little hometown of Schlitz. "The children weren't allowed to play in sandboxes anymore, they couldn't eat fresh vegetables anymore, or mushrooms," she later recalled. She pictured what it would be like if it had occurred even closer, at Grafenrheinfeld, her nearest local nuclear plant. "I thought: what if this kind of catastrophe happened right in the centre of Germany? I had to warn people."

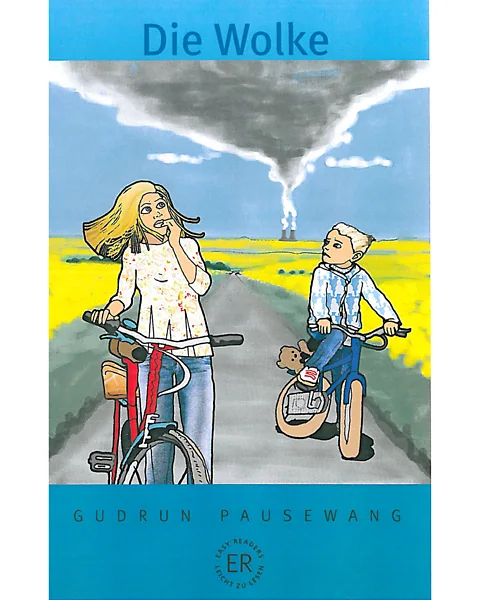

Four weeks later, she began to write a story about a fictional nuclear accident, and a girl's struggle to survive the aftermath. She titled it Die Wolke ("The Cloud", published in English as Fall-Out).

Ravensburger

RavensburgerThe Cloud went on to sell more than a million copies, and defined an entire era. To many West Germans – especially the so-called "Generation Pausewang" who read it as children and teens – it is as emblematic of the 1980s as stonewashed jeans, Nena and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Schools have been named after Pausewang, environmental organisations have showered her with prizes for spreading anti-nuclear awareness, and Germany's Green Party has celebrated her work with screenings of a film version of The Cloud. After the nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011, the book shot back into German bestseller lists. The fact that she used real-life locations in the story – Schlitz, and the Grafenrheinfeld reactor – added to its visceral impact. But Pausewang's ultra-bleak, unflinching style also drew criticism. "She brought the apocalypse into children's bedrooms," wrote a critic for Die Welt after the author's death in 2020. She "gave thousands of schoolchildren nightmares," claimed another. To this day, critics argue over whether she empowered children – or traumatised them for life.

Era defining

"The Cloud was incredibly timely, because it was written right after Chernobyl. And it coincided with that entire discussion around the risks and danger of nuclear power, but also, in the late 80s, the end of the Cold War, disarmament, and reconciliation," says Cornelia Rémi, a German literature scholar and one of the jurors who awarded Pausewang the German Youth Literature Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.

The Cloud begins with an ordinary school day. Fourteen-year-old Janna-Berta is looking out of the window, admiring the cherry blossoms. She leads an idyllic life in Schlitz with her parents and her little brother Uli. Her sweet, caring grandmother, Oma Berta, spoils her with homemade waffles: "One was safe at Oma Berta's place, knowing nothing bad could happen, that goodness was always visible and triumphed, and evil was even more visible and was defeated." Suddenly, the sound of a siren disrupts the lesson, the school is evacuated, someone cries: "Grafenrheinfeld! Alarm in Grafenrheinfeld!" No one seems to know what's going on; the adults run for their lives, the children are left to their own devices. "They keep talking about some sort of cloud," Janna-Berta's brother says, listening to the radio. "And that cloud – it's toxic."

The siblings escape the town on their bikes, and the narrative begins to veer between chaotic scenes of societal collapse, and flashbacks to Germany's past. "It's already starting with the refugees. Just like in 1945," mutters a woman who refuses to let Janna-Berta into her house. "Hitler would have murdered us in the gas chambers, with our messed-up genes," says one of Janna-Berta's fellow survivors. Even the seeming idyll of the before-times is questioned: Oma Berta, it turns out, was an ardent Nazi in her youth.

Alamy

AlamyPausewang wrote almost 100 books, not all of them bleak. But her name is mostly associated with so-called "Katastrophenbücher", "catastrophe books", novels for children and teens that explore every imaginable social, environmental and political cataclysm. The Cloud is, in fact, one of the lighter reads in that category. In another Pausewang classic, The Last Children of Schewenborn (1983), a group of children survive nuclear war, pick their way through the ruins, then die agonising deaths. In the 1993 novel Der Schlund (The Maw or The Abyss), a Hitler-like dictator seizes power in 1990s Germany; the protagonist loses almost her entire family, and is arrested at the end.

"For a certain generation, and I guess I'm part of that, it's one of those 'reading shocks' you remember," Rémi tells BBC Culture. The books follow a distinctive, downward-spiralling narrative path, with things going from bad to worse, to even worse. The young protagonists "are thrown into situations that they can't grasp and can't understand," says Rémi. "And whenever adults appear and temporarily create some sort of order, it tends to collapse within the next breath. It's a world where from one second to another, everything can shatter. It's very dystopian, very dark, very sad." She sums up the average Pausewang reader's experience as feeling "repulsed, disgusted, depressed, frightened, and then, cast out of the story without any glimmer of hope."

While typically seizing on real-life, external threats or dangers, Pausewang's books ultimately reflect her lifelong reckoning with her own conscience. Born in 1928 and raised in a German family in what is now the Czech Republic, Pausewang was, in her own words, a "fervent National-Socialist" as a teenager. From the age of 10 to 17 she belonged to various Nazi youth organisations: "I believed in Hitler and his message right until the end." She cried when she heard that Hitler had died. At the end of the war, the Pausewangs joined millions of Germans who escaped westwards as the Red Army closed in.

Pausewang wrote openly and critically about her Nazi past, and published several autobiographical novels about her childhood and youth, known as the Rosinkawiese (Rosinka Meadow) series. Her opposition to nuclear power was, in her view, a way of learning from past wrongs. As she put it in an essay explaining why she wrote The Cloud: "I don't want my grandchildren and great-grandchildren to ask me (the way grandchildren and great-grandchildren asked their parents after the Nazi era): 'And you? Why didn't you do anything against it?'"

In 2015, Pausewang, then 87, agreed to accompany Hannes Vollmuth, a journalist and editor at Germany's Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, on a road trip to Grafenrheinfeld. Germany had decided to abandon nuclear power, and the reactor at the centre of The Cloud was about to be decommissioned.

"Gudrun Pausewang's books were the first books that really shook me – really, really shook me," says Vollmuth, who read them as a child in the 1990s. "One might argue that the effect wasn't a particularly positive one, but I did feel the full blast of the power of literature."

Vollmuth had a very personal link to her work. He grew up not far from Grafenrheinfeld, which the children in the area called "the cloud machine", because of the steam rising from its cooling towers. After reading The Cloud, which featured Grafenrheinfeld with its real name, he became intensely worried about an accident happening there. Pausewang's nuclear novels "did instil a certain fear in me, which doesn't necessarily play a part in my everyday life, but which can be triggered," for example by news events like the recent fighting around a nuclear plant in Ukraine, he tells BBC Culture.

Alamy

AlamyThe road trip could have resulted in a neat narrative arc: the author and her younger reader confronting their vanquished old enemy – the local reactor – and laying their fears to rest. Yet Pausewang showed no sign of triumph. Instead, she reminded Vollmuth that there were still plenty of other global problems, from war and poverty to delapidated nuclear plants in other parts of the world. It was a perhaps characteristically bleak reaction from an author who once said: "When [my publisher] began asking only for cheerful texts, I looked for another publisher."

Some see a disturbing twist in that devotion to doom. As several critics have pointed out, Pausewang's intentions may have been noble, but the books at times read more like gory thrillers, indulging in graphic descriptions of death, degradation, oozing wounds and "radioactive mutants" as if staging an end-times carnival.

Gory detail

"One really striking thing is that the descriptions [of death and suffering] are so over-abundant, far beyond the stated goal of wanting to warn people," says Jenny Willner, an assistant professor of comparative literature at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. In an analysis of The Last Children of Schewenborn, she compares the effect to the morbid thrill of a zombie movie – with the crucial difference that zombie movies honestly present themselves as entertainment. "I find Gudrun Pausewang's literature eerier and scarier than any zombie movie, because it's accompanied by this kind of caring, maternal gesture."

Willner points out that hard-hitting children's novels as such were not a uniquely German phenomenon: Scandinavia also experienced a wave of realist literature, starting in the 1970s. In the UK, a 1980s graphic novel and animation, When the Wind Blows by Raymond Briggs, memorably captured people's nuclear fears. (In the US, an example of a "catastrophe book" might be The Wave by Todd Strasser, an early 1980s novel about Fascism taking hold of a US high school.) And yet Pausewang's legacy goes further, and has become almost myth-like in Germany, Willner tells BBC Culture: "When you have West German friends of my generation, and it's late at night, you start hearing these horror stories, about this Gudrun Pausewang, these books they read in their childhood."

Clasart Film and TV Productions/Alamy

Clasart Film and TV Productions/AlamyShe sees this legacy reflected in present-day German horror films such as the Netflix hit series, Dark: "You can better understand those kinds of German scary movies, and their 1980s roots, if you read Gudrun Pausewang."

Even Pausewang's admirers concede that the books can be painful. "It was so overwhelming, this scenario, so huge, that I didn't know how to cope with it, as a child," says Rémi, recalling the effect of reading The Last Children of Schewenborn. Then again, she argues, it's a realistic depiction of how children experience systemic meltdown. "Her texts encourage readers to engage with big questions: the environment, anti-nuclear issues, but also, especially in her later years, the Nazi era, Fascism, dictatorship and political radicalisation." And by rejecting a heroic narrative, one in which the child might triumph through some individual act of bravery or cunning, Pausewang places the responsibility squarely on the adults, and the system they created. (She also had less subtle ways of getting that message across: In The Last Children of Schewenborn, the children scrawl "Cursed Parents!" on a wall, and one of them cries: "The bomb is your fault!".)

Overall, Rémi says, the question that haunted Pausewang remains hugely relevant today, at a time of climate change and conflict: "What did we inherit from the past, and what are we passing on to the next generation?"

Given that I am a member of Generation Pausewang, re-reading The Cloud for this article did make me reflect on how her gloomy outlook shaped me. I devoured her books as a child and teenager, and admire her commitment to truth-telling. But I also wish she had, perhaps, broadened her view of human nature just a little, and allowed for the possibility that people do sometimes choose to be brave, hopeful, altruistic and forgiving – and thrive. Of course, Pausewang would have found that suggestion naïve, and worse, patronising. As she once said, at the age of seven she already disliked books with a happy ending, and felt the writers didn't take her seriously. She promised herself: "If I'm ever going to become a writer, I will take my readers seriously, regardless of whether they are six, 16 or 60. And I did become a writer, and I do take my readers seriously."

Sophie Hardach is a journalist and writer living in London. Her latest novel, Confession with Blue Horses, was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.